WASHINGTON — With monkeypox cases on the decline nationally, federal health officials expressed optimism on Thursday that the virus could be eliminated in the United States, though they cautioned that unless it was wiped out globally, Americans would remain at risk.

“Our goal is to eradicate; that’s what we’re working toward,” Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, the deputy coordinator of the White House monkeypox response team, said during a visit to a monkeypox vaccination clinic in Washington. He added, “The prediction is, we’re going to get very close.”

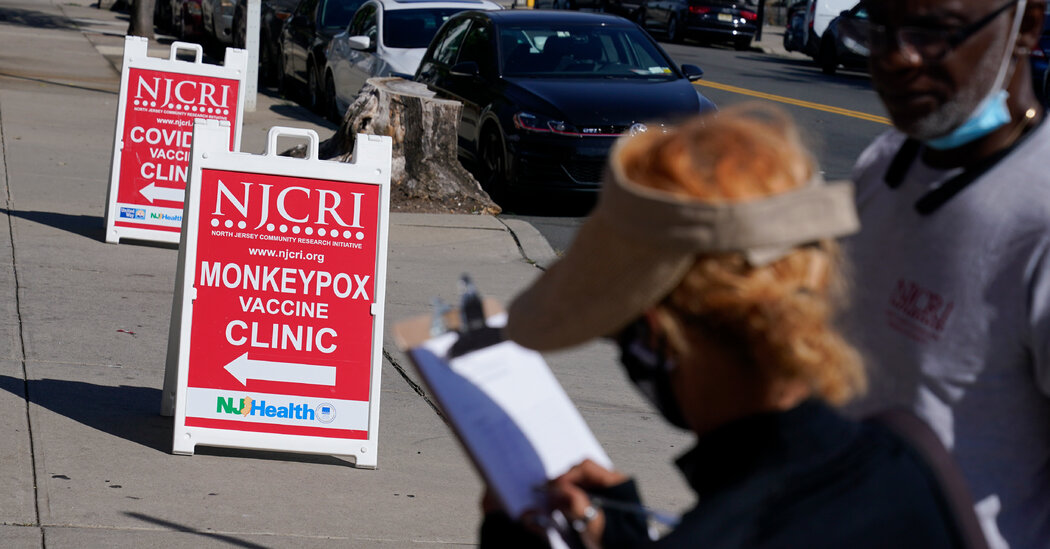

Dr. Daskalakis was joined by President Biden’s health secretary, Xavier Becerra, and the response team’s coordinator, Robert J. Fenton Jr., who echoed his optimism. The visit to the clinic was intended to spotlight efforts by the District of Columbia to close the racial gap in vaccination against monkeypox — a major goal of the Biden administration.

“The president said from the very beginning, ‘Get on top of this, and then stay ahead of it,’” Mr. Becerra told reporters. “And we can’t say we really stayed ahead of it if we’re leaving certain communities behind.”

Dr. Daskalakis, an infectious disease expert who previously ran the division of H.I.V. prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was brought onto the monkeypox response team by Mr. Biden last month.

What to Know About the Monkeypox Virus

What is monkeypox? Monkeypox is a virus similar to smallpox, but symptoms are less severe. It was discovered in 1958, after outbreaks occurred in monkeys kept for research. The virus was primarily found in parts of Central and West Africa, but recently it has spread to dozens of countries and infected tens of thousands of people, overwhelmingly men who have sex with men.

On Thursday, Dr. Daskalakis did not give a timeline for ending the outbreak in the United States, saying only that he was looking into his “midterm crystal ball.” But he said he expected that, over time, cases would drop to a trickle and infections would emerge only sporadically, enabling health officials to isolate and vaccinate the close contacts of those infected — and end the outbreak in the process.

That strategy, known as ring vaccination, was used in the global campaign to stamp out smallpox, which was declared eradicated in 1980.

But there is a major difference between monkeypox and smallpox: Smallpox occurs only in humans, while monkeypox also occurs in animals. The existence of an “animal reservoir” means there will always be the risk of spread to humans, said Dr. Michael T. Osterholm, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota.

“Eradication is a very sacred word in public health; to eradicate means it is gone permanently, and the only virus we have done that with so far is smallpox,” Dr. Osterholm said.

He said a better word was “elimination,” and a better comparison would be measles. “We’ve had a major measles elimination program in this country and have greatly reduced the occurrence of measles, but the challenge today remains the introduction of the virus from individuals around the world,” Dr. Osterholm said.

The first U.S. cases in the current monkeypox outbreak emerged in May. The disease, which in the United States has occurred primarily in men who have sex with men, is characterized by fever, muscle aches, chills and lesions. It is rarely fatal in wealthy countries like the United States, but it can cause excruciating pain. The current outbreak is unusually large; the last big monkeypox outbreak in the United States occurred in 2003, when 47 confirmed and probable cases were reported in six states.

In the current outbreak, the United States accounts for more than a third of the roughly 65,000 cases reported worldwide; as of Thursday, the C.D.C. had reported nearly 25,000 cases in the country. An average of about 200 cases per day are still being reported in the United States, though that figure is down significantly from the height of the outbreak in August.

The decline is a relief to Biden administration officials, who came under sharp criticism for their response — and especially a shortage of the vaccine — in the early days of the outbreak. Critics, including many gay rights activists, said the administration failed to move aggressively to order vaccine doses and distribute them before many gay men were infected during Pride celebrations in June.

One of those activists, James Krellenstein, a founder of PrEP4All, an advocacy group, said Dr. Daskalakis’s comments were premature. He said a shortage of federal funds to research monkeypox, and a lack of answers to basic questions, made it too soon to predict an end to the outbreak.

“This is the first time that we really have seen a large outbreak of monkeypox with sustained human-to-human transmission, and there remain many scientific unknowns,” Mr. Krellenstein said, adding in a reference to President George W. Bush, “Let’s not get into ‘mission accomplished’ landing on an aircraft carrier territory here.”

The vaccine shortage led to sharp racial disparities that the administration is now trying to address. Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, a professor of epidemiology and medicine at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, said she shared Dr. Daskalakis’s optimism that the outbreak could be brought under control, but only with intense efforts to reach underserved populations.

“The risk,” she said, “is that you have these populations that are hard to reach, often the poor and people of racial and ethnic minorities who are less aware, have less access. They tend to sometimes fall behind, as we are seeing, in terms of vaccination.”