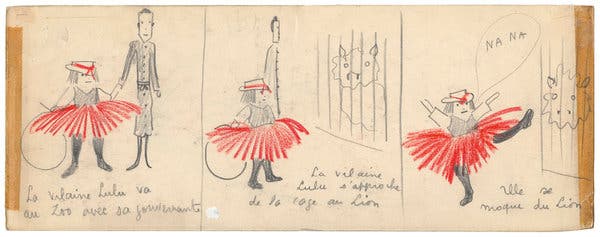

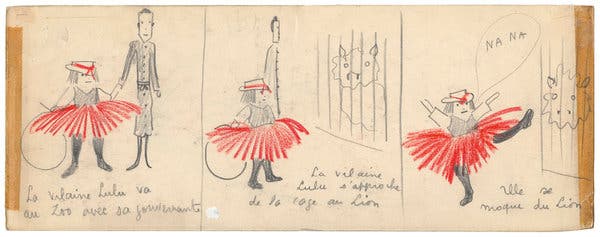

In 1967, Yves Saint Laurent introduced La Vilaine Lulu, the beastly little star of a comic book — or bande dessinée — that he wrote and illustrated.

Short and squat with a froggy face, wearing a beribboned boater and a scarlet cancan skirt that she would flip up to expose her naked derrière, La Vilaine Lulu terrorized her teachers, schoolmates, passers-by — well, everyone, really. A devil child, that Lulu.

Now she is a cornerstone for “Mode et Bande Dessinée” (“Fashion and Comic Books”), which its organizers say is the first major exhibition to take a comprehensive look at fashion in comic books and graphic novels, through Jan. 5 at the Cité Internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image in Angoulême, France.

As the fall couture season begins on Monday in Paris, the show is a reminder that, while luxury fashion is often viewed as elitist, it has a way of trickling down commercially and artistically to unexpected yet highly accessible places — and vice versa. Comic-Con International and the elaborate character outfits worn by fans are just one flash of the impact.

“Jean Paul Gaultier, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac and Thierry Mugler were obviously influenced by B.D.s,” said Thierry Groensteen, the exhibition’s curator, using the French nickname, pronounced “bay-days,” for comic books. “You see it in Castelbajac’s sweater dresses, with B.D. motifs, and Mugler’s Cat Woman suit, with its cagoule with little ears.” Both are represented in the show.

Two hours by train from Paris, Angoulême is France’s capital of comic books. Each year since 1974, it has hosted the Angoulême International Comic Festival, a four-day event that last year drew more than 200,000 B.D. enthusiasts. The Cité, which opened in 1990, now houses 13,000 original plates and 250,000 B.D.s — the world’s second largest collection of French-language comics (after the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University in Columbus).

Pierre Lungheretti, the Cité’s director, said its collection traces the genre, known officially in France as “the 9th art,” from “the birth of comic books in the 19th century to today.”

In addition to the museum, which has about 70,000 visitors a year, there is a reference library, two screening rooms, bookstore, a restaurant and residences where as many as 50 comic book authors are invited to spend from three months to four years working on their latest projects.

So loved are comic books in France that the Ministry of Culture has declared 2020 the “Année de la B.D.,” with dozens of events scheduled throughout the country.

“Twenty-five years ago, about 500 comic books were published annually” around the world, Mr. Lungheretti said and now it’s 5,000. “In a world saturated with images and graphics, comic books open the human imagination and an interpretation of society that allows for satire, humor, and poetry.”

Also some great clothes.

Curiously, Mr. Lungheretti said, no museum other than the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its 2008 “Superheroes: Fantasy and Fashion” show has mounted a thorough exploration of the relationship between comics and clothing. And yet, “there have always been characters who were dressed in very identifiable or signature outfits,” he said, mentioning Bécassine, a young Breton housemaid who first appeared in a French weekly in 1905 and traditionally has been depicted in a long green peasant dress, white apron, head scarf and clogs.

“Even Tintin has a look,” Mr. Lungheretti said.

The Cité’s six-part exhibition begins with a study of similar pen strokes found in renderings by fashion designers like Elsa Schiaparelli and Saint Laurent and such B.D. luminaries as Winsor McCay, the early 20th-century American cartoonist of “Little Nemo,” and Jean Giraud, the French artist also known as Moebius, who died in 2012.

In this section La Vilaine Lulu pops up at her most naughty — hosing chums with ice water, stringing up innocents, lashing adults to bedposts or tossing them out skyscraper windows — in original drawings on loan from the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris. “It’s remarkable to see that Saint Laurent chose this mode of expression to illustrate his universe, with an imagination that was very tortured, even violent,” Mr. Lungheretti said, adding that the comic “explains a lot who he was.”

The show then turns to B.D. homages and influences on the catwalk and in advertising, such as Parfums Dior’s Eau Sauvage campaign of 2001, which featured Corto Maltese, the enigmatic title character of Hugo Pratt’s high seas adventure series. There also are panels from Marvel’s Millie the Model, which ran from 1945 to 1973, as well as Les Triplés, a regular comic feature about three precocious children that has appeared in Madame Figaro, Le Figaro’s weekly fashion supplement, since 1983.

For a 1990 strip, the Triplés author Nicole Lambert, herself a former model, drew a camellia-adorned black velvet boater just like one Karl Lagerfeld had originally designed for Chanel (the cartoon and hat are both on display). Though perhaps no B.D. so closely joined the shows and the comic squares as Annie Goetzinger’s “Jeune Fille en Dior,” or “Young Woman in Dior,” a 2013 graphic novel that recounted the adventures of a junior fashion reporter covering the couture house’s first défilé.

As the brand prepares for yet another, it could be required reading on the front row.