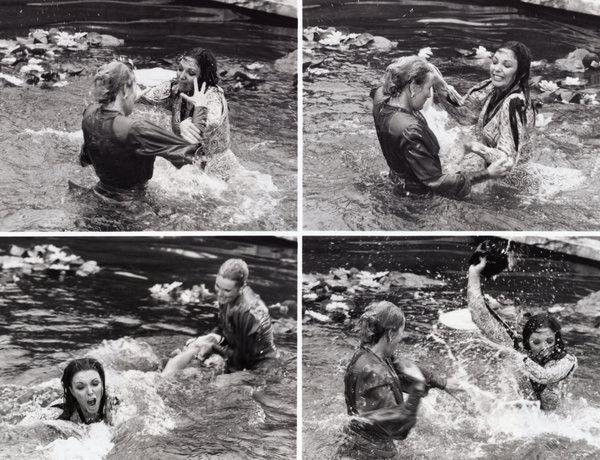

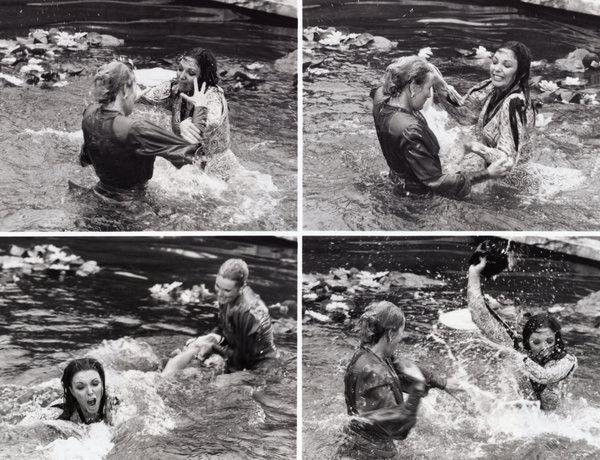

Physical altercations between rival female characters were a common plotline on the 1980s ABC television drama “Dynasty.”CreditBettmann Archive, via Getty Images

There is a word that starts with “c” that is exclusively used to describe women. Usually, it’s deployed when we are being argumentative, standing up for ourselves, or otherwise not behaving as nicely as we’re expected to.

Catfight.

The word, which originally referred to a physical clash between women (and has no equivalent for men), has been part of our culture for centuries. It was used as early as 1854 to describe Mormon women fighting over their shared husband. Their houses, Benjamin G. Ferris writes in his book “Utah and the Mormons,” were designed to keep women “as much as possible, apart, and prevent those terrible catfights which sometimes occur, with all the accompaniments of billingsgate [vulgar and coarse language], torn caps, and broken broomsticks.”

It suggests a dispute petty and less than human.

But lately, as we’re examining our treatment and perception of women in sweeping ways, the word hasn’t cropped up with as much frequency. And the groupthink that propelled both men and women to view female-on-female feuds as worthwhile entertainment is beginning to smell like a second-day litter box.

Catfights have had a long history of amusing drag queens and turning on heterosexual men, including in pornography. As far back as the 1950s, women wrestling in lingerie and high heels was a staple of fetish films. The model Bettie Page, who starred in many of them, said in the documentary “Bettie Page Reveals All,” “For some reason, men like to see women … one spanking the other. Why, I don’t know.”

The word has also been used to belittle women competing and disagreeing in all sorts of arenas, whether we’re vying for a promotion at work or running for president.

These days, however, calling any conflict between women a catfight is understood to be sexist, and enthusiasm has generally dampened for women fighting. In 2018, when Cardi B and Nicki Minaj got into a shoe-throwing altercation at a party, the majority of the media coverage about called it simply a fight or a brawl, and while there was definite interest in it and whatever caused it, the conflict was treated similarly to one between two male stars.

This year, many royal watchers have rejected the emerging tabloid story line that the princesses Kate Middleton and Meghan Markle don’t like one another. “In the fairytale that is never told, two princesses meet and they get on fine, almost like normal people,” the columnist Suzanne Moore wrote in The Guardian. “Whoever is selling these feud fantasies should realise us non-princesses just don’t buy them. We moved on a long time ago.” Kensington Palace also put out a rare statement denying a confrontation the two supposedly had, and the two women were recently photographed greeting each other with a friendly double-cheek kiss.

When Khloe Kardashian and the father of her baby, Tristan Thompson, broke up, the Kardashians originally tried to blame Jordyn Woods, a family friend who was rumored to be involved with him. Khloe tweeted, “You ARE the reason my family broke up!” — to the ire of her followers. “Why is Khloe placing so much blame on Jordyn and directing her anger towards her vs the man who had an obligation to be faithful in his relationship with her? Idk I just hate seeing all the blame thrown on her,” Alissa Ashley, in Oakland, Calif., tweeted. Within hours, Khloe took back her original sentiment, tweeting, “Jordyn is not to be blamed for the breakup of my family. This was Tristan’s fault.”

Deborah J. Borisoff, a professor of media culture and communication at New York University, thinks we’re doing our best to make small corrections in a culture that is still struggling to take women seriously.

“We’re not used to seeing so many women with so much power and so many resources, who are so visible, in entertainment, in business, and the Kardashians are a business, and these two young women in England,” she said. “We don’t have a template of just seeing them as being strong people, as powerful performers, or politicians, or powerful in business, so we’re trying to self monitor, to not go to the convenient label that is no longer appropriate.”

The catfight is very much alive, though, on reality television franchises such as “The Real Housewives” and “The Bachelor.” Women plotting against each other, and eventually resorting to hair pulling and champagne hurling, is as much of a go-to story line today as it was in the 1980s on the nighttime soap opera “Dynasty,” when Joan Collins’s character boosted ratings by flinging pond scum down her rival Krystle’s blouse.

Caroline Heldman, the executive director of the Representation Project, which aims to dismantle gender stereotypes, and a co-author of “Sex and Gender in the 2016 Presidential Election,” is almost certain the word will be used in the Democratic primary to demean the unprecedented number of women who have already entered the race. “I see the catfight label framing a lot of what happens when the primary heats up,” she said. “It’s such a good diminutive label. It suggests the fight isn’t a real fight, but more important, catfights exist to titillate heterosexual men. It reduces female presidential candidates to not-serious contenders.”

But Ms. Heldman has hope that the catfight may soon become obsolete (except, of course, between actual cats). She wasn’t sure that some of her students at Occidental College, where she teaches politics, had ever heard the term, and texted a 22-year-old female student to ask if she was familiar with it. The response came back seconds later: “No ma’am.”

Kayleen Schaefer is the author of “Text Me When You Get Home,” a book about female friendship. This article draws from her research.