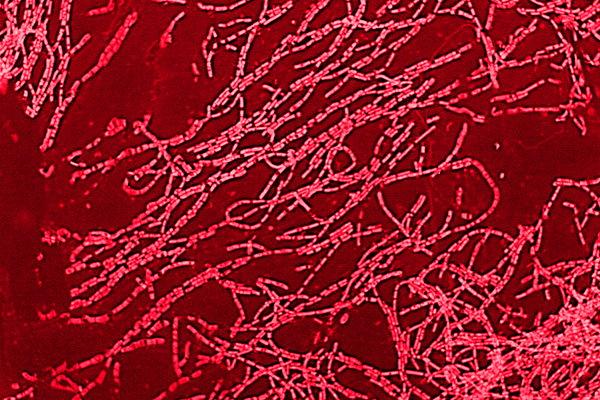

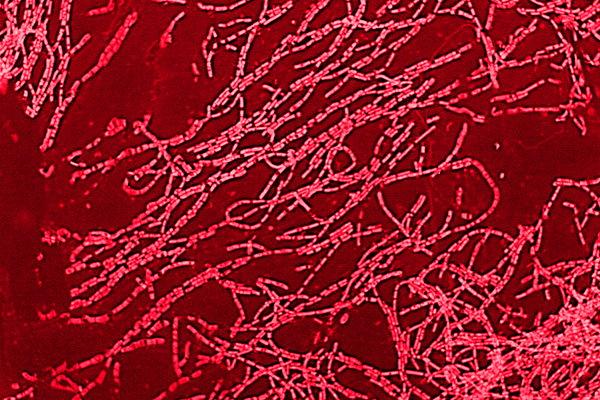

WASHINGTON — Pound for pound, the deadliest arms of all time are not nuclear but biological. A single gallon of anthrax, if suitably distributed, could end human life on Earth.

Even so, the Trump administration has given scant attention to North Korea’s pursuit of living weapons — a threat that analysts describe as more immediate than its nuclear arms, which Pyongyang and Washington have been discussing for more than six months.

According to an analysis issued by the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey last month, North Korea is collaborating with foreign researchers to learn biotechnology skills and build machinery. As a result, the country’s capabilities are increasing rapidly.

“North Korea is far more likely to use biological weapons than nuclear ones,” said Andrew C. Weber, a Pentagon official in charge of nuclear, chemical and biological defense programs under President Obama. “The program is advanced, underestimated and highly lethal.”

The North may want to threaten a devastating germ counterattack as a way of warding off aggressors. If so, its bioweapons would act as a potent deterrent.

But experts also worry about offensive strikes and agents of unusual lethality, especially the smallpox virus, which spreads person-to-person and kills a third of its victims. Experts have long suspected that the North harbors the germ, which in 1980 was declared eradicated from human populations.

Worse, analysts say, satellite images and internet scrutiny of the North suggest that Pyongyang is newly interested in biotechnology and germ advances. In 2015, state media showed Kim Jong-un, the nation’s leader, touring a biological plant, echoing his nuclear propaganda.

But compared to traditional weapons, biological threats have a host of unsettling distinctions: Germ production is small-scale and far less expensive than creating nuclear arms. Deadly microbes can look like harmless components of vaccine and agricultural work. And living weapons are hard to detect, trace and contain.

The North’s great secrecy makes it hard to assess the threat and the country’s degree of sophistication. Today, the North might well have no bioweapons at all — just research, prototypes, human testing, and the ability to rush into industrial production.

A light micrograph of anthrax bacteria. A single gallon of anthrax, properly distributed, could wipe out all of humanity.CreditBiomedical Imaging Unit, Southampton General Hospital/Science Source

Still, Anthony H. Cordesman, a former Pentagon intelligence official now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said the North “has made major strides” in all technical areas needed for the production of a major germ arsenal.

In unclassified reports, the Trump administration has alluded to the North’s bioweapons program in vague terms. President Trump did not broach the subject of biological weapons during his meeting with Mr. Kim in Singapore, according to American officials.

The lack of detail and urgency is all the more surprising given that John R. Bolton, Mr. Trump’s national security adviser, has long described it as a regional and even a global threat.

In 2002, as under secretary of state for arms control and international security in the George W. Bush administration, Mr. Bolton declared that “North Korea has one of the most robust offensive bioweapons programs on Earth.”

Last century, most nations that made biological arms gave them up as impractical. Capricious winds could carry deadly agents back on users, infecting troops and citizens. The United States renounced its arsenal in 1969.

But today, analysts say, the gene revolution could be making germ weapons more attractive. They see the possibility of designer pathogens that spread faster, infect more people, resist treatment, and offer better targeting and containment. If so, North Korea may be in the forefront.

South Korean military white papers have identified at least ten facilities in the North that could be involved in the research and production of more than a dozen biological agents, including those that cause the plague and hemorrhagic fevers.

United States intelligence officials have not publicly endorsed those findings. But many experts say the technological hurdles to such advances have collapsed. The North, for instance, has received advanced microbiology training from institutions in Asia and Europe.

Bruce Bennett, a defense researcher at the RAND Corporation, said defectors from the North have described witnessing the testing of biological agents on political prisoners.

Several North Korean military defectors have tested positive for smallpox antibodies, suggesting they were either exposed to the deadly virus or vaccinated against it, according to a report by Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Smallpox claimed up to a half billion lives before it was declared eradicated. Today, few populations are vaccinated against the defunct virus.

Starting three years ago, Amplyfi, a strategic intelligence firm, detected a dramatic increase in North Korean web searches for “antibiotic resistance,” “microbial dark matter,” “cas protein” and similar esoteric terms, hinting at a growing interest in advanced gene and germ research.

According to the Middlebury Institute analysis, at least 100 research publications that were jointly written by North Korean and foreign scientists have implications for military purposes, such as developing weapons of mass destruction. The collaborations may violate international sanctions.

Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., a North Korean military analyst, said it is entirely likely that the North has already experimented with gene editing that could enhance bacteria and viruses.

“These are scientists, and scientists love to tinker,” he said.

Western concerns about the North’s program jumped in June 2015, after Mr. Kim posed in a white lab coat alongside military officers and scientists in a modern-looking pesticide facility called the Bio-Technical Institute, his arms outspread toward shiny lab equipment.

The plant allegedly produced pesticides. The photos showed enormous fermenters for growing microbes, as well as spray dryers that can turn bacterial spores into a powder fine enough to be inhaled. Mr. Kim was beaming.

Melissa Hanham, a scholar who first identified the site’s threatening potential, said equipment model numbers showed that the North had obtained the machinery by evading sanctions — laundering money, creating front companies or bribing people to buy it on the black market.

She said the evidence suggests the North succeeded in building a seemingly harmless agricultural plant that could be repurposed within weeks to produce dried anthrax spores.

Arms-control analysts say intrusive inspections are needed to see whether a facility is intended for peaceful aims or something else.

“A nuclear weapons facility has very visible signals to the outside world,” Mr. Bermudez said. “We can look at it and immediately say, ‘Ugh, that’s a nuclear reactor.’ But the technology for conducting biological weapons research is essentially the same as what keeps a population healthy.”

Americans felt the sting of bioweapons in 2001 when a teaspoon of anthrax powder, dispatched in a handful of envelopes, killed five people, sickened 17 more and set off a nationwide panic. The spores shut down Congressional offices, the Supreme Court and much of the postal system, and cost about $320 million to clean up.

Federal budgets for biodefense soared after the attacks but have declined in recent years.

“The level of resources going against this is pitiful,” said Mr. Weber, the former Pentagon official. “We are back into complacency.”

Dr. Robert Kadlec, the assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services, said, “We don’t spend half of an aircraft carrier on our preparedness for deliberate or natural events.”

The National Security Council’s top health security position was eliminated last year, so biological threats now come under the more general heading of weapons of mass destruction.

Still, on the Korean Peninsula, troops gird for a North Korean attack. According to the Belfer report, American forces in Korea since 2004 have been vaccinated against smallpox and anthrax.

Recently, Army engineers sped up the detection of biological agents from days to hours through Project Jupitr, or the Joint United States Forces Korea Portal and Integrated Threat Recognition, a Department of Defense spokeswoman said.

The comptroller general of the United States, after a request from the House Armed Services Committee, is currently conducting an evaluation of military preparedness for germ attacks.

“If you’re a country that feels generally outclassed in conventional weapons,” Ms. Hanham said, a lethal microbe such as anthrax might seem like a good way “to create an outsized amount of damage.”

Such an attack would maximize casualties, she said, while terrorizing the uninfected population. For North Korea, Ms. Hanham added, “That would be the twofold goal.”

Follow Emily Baumgaertner on Twitter: @Emily_Baum