Nicholas Gray, the founder of Gray’s Papaya, a storefront hot-dog stand whose culinary eccentricity, competitive prices, clever sloganeering and apparent immutability earned the affection of New Yorkers young and old, rich and poor, died on Friday at a hospital in Manhattan. He was 86.

The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, his daughter Natasha Gray said.

Pastrami on rye and bagels and lox, to name two canonical pairings of New York cuisine, possess a kind of self-evident logic. Papaya juice and hot dogs, the specialty of Gray’s Papaya, seem, conversely, like favorites of separate — perhaps opposing — sociocultural groups.

Yet this odd couple gained Original Ray’s Pizza-like ascendancy in local dining. In addition to Gray’s Papaya on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and Papaya King on the Upper East Side — the leading purveyors — New York establishments selling hot dogs and papaya juice have included 14th Street Papaya, Chelsea Papaya, Empire Papaya, Papaya International, Papaya World, Papaya World II, Papaya Heaven and Papaya Paradise.

According to most accounts, the pairing’s origins lie in the 1930s, when Constantine Poulos, a New York deli proprietor partial to tropical vacations, started selling the juice of exotic-seeming fruits. (Some have described the enterprise as New York’s first juice bar.) In later years he added hot dogs to the menu and crowned his Upper East Side storefront Papaya King.

The papaya-frankfurter combination was not yet a major local phenomenon when, one day in 1973, Mr. Gray, a recently divorced Wall Street stockbroker who was discontented at work, walked by Papaya King, at East 86th Street and Third Avenue.

It was crowded with happy people. The tropical juice reminded him of his homeland, Chile. The bright neon sign and the hot dogs spoke to his fondness for Americana.

He quit his job and entered a franchise agreement with Papaya King to open a location at 72nd Street and Broadway on the Upper West Side. After two years, he went independent and named his restaurant Gray’s Papaya.

Soon his knockoff was itself being knocked off.

The variants tend to share essential traits. Like the espresso bars of Italy, the papaya joints have no seats; you chew standing. In milder months the doors are perpetually open to the breeze and the sound of honking cars, as if the eateries are extensions of the sidewalk. The hot dogs are cooked on griddles, not in the so-called dirty water of hot-dog carts. And the papaya drinks, often characterized as chalky, taste not like papaya so much as a soft echo of it.

If Papaya King had the tradition and brand recognition of the Yankees, then Gray’s Papaya was the Mets, a scruffy expansion team. It became a destination for an after-school snack, a quick bite before a Lincoln Center show, a meal on-the-go during the workday and a treat after a romp in Central Park.

The store announced its opening with good news for the hot dog hoi polloi: 50 cent hot dogs, compared with Papaya King’s 75. (The price remained 50 cents until 1999). In 1982, Mr. Gray began offering what he called the Recession Special: two dogs and a tropical juice for $1.95. That bargain, which withstood several recessions, now goes for $6.45.

He loathed raising prices. “It’s always very traumatic for me as well as for the customers,” he told The New York Times in 2008. He once put up a sign that read: “We are getting killed by galloping inflation in food costs. Unlike politicians we cannot raise our debt ceiling and are forced to raise our very reasonable prices. Please don’t hate us.”

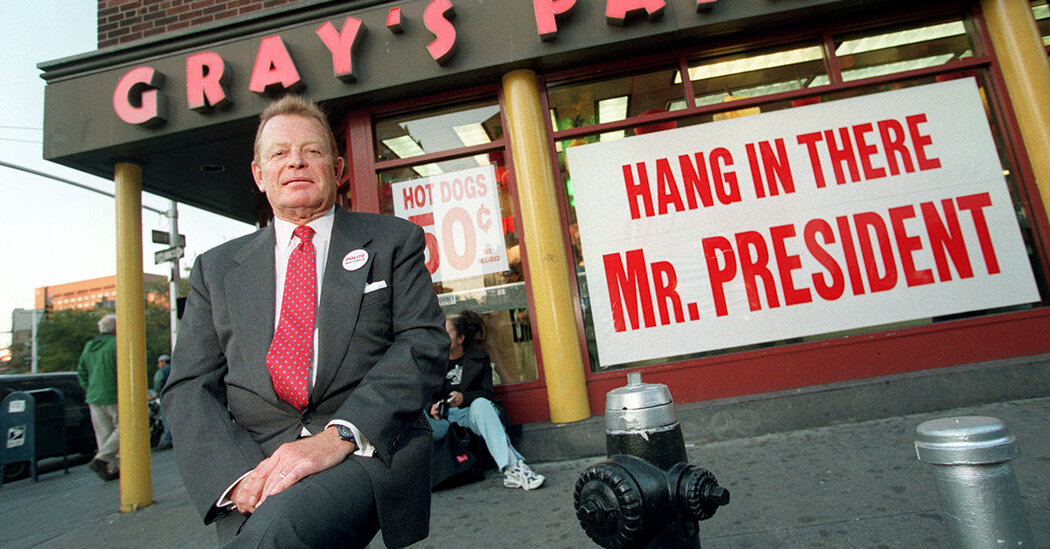

That sign and many others lent the restaurant a fanciful yet insistent tone. Upon opening, Mr. Gray put up a sign he made himself proclaiming a “Hot Dog Revolution!” The storefront promises “Nobody but nobody serves a better frankfurter” and “No Gimmicks! No Bull!” A sign inside identifies papaya as “the aristocratic melon of the tropics.”

Signs aired Mr. Gray’s political views. “Hang in there Mr. President,” one exhorted Bill Clinton as he faced impeachment in 1998. In 2007, Mr. Gray promised “free hot dogs on Inauguration Day” if Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg ran for president the next year and won. Mr. Gray’s public positions, however opinionated, were consistently positive. Gray’s Papaya sold buttons that said, “Polite New Yorker.”

Decades after its founding, Gray’s Papaya had become a New York institution.

“Rent stabilization was an indelible part of New York life, like Gray’s Papaya,” Nora Ephron wrote in The New Yorker in 2006. “It would never be tampered with.”

Nicholas Alexander Buchanan Gray Anguita was born on Jan. 17, 1937, in Valparaiso, Chile. His father, Alexander, was a British bank manager sent abroad by his employer. His mother, Nieves (Anguita) Gray, a native Chilean, was a homemaker.

Nick attended the Sherborne School in southwest England and after graduation washed dishes at a radar station in the Arctic Circle to earn money for college.

While attending McGill University in Montreal, he met Patricia Osterman, a student at Syracuse University. The two of them dropped out of college, married and started a family on the Upper West Side.

Patricia’s father, Lester Osterman, was a Broadway producer, and Mr. Gray helped manage his productions before working on Wall Street. By 1975, Mr. Gray and his wife had divorced.

He also ran a Gray’s Papaya outlet in Greenwich Village from 1987 to 2014, and opened two locations on Eighth Avenue in Midtown, the last of which closed in 2021.

Rising commercial rents wiped out many of the papaya establishments. Along with the original Gray’s location and a newly relocated Papaya King, set to open soon across Third Avenue, New York retains Papaya Dog on West Fourth Street, Chelsea Papaya on West 23rd and Len’s Papaya in the Whitehall Ferry Terminal in the financial district.

In 1989, a frat brother of Mr. Gray’s from McGill told his daughter, Rachael Eberts, an incoming architecture student at Parsons School of Design, to look up Mr. Gray when she got to New York. They married in 1996.

In addition to his daughter Natasha, Mr. Gray is survived by his wife; another daughter from his first marriage, Sheila Gray; a daughter and a son from his second marriage, Tessa and Rufus Gray; a sister, Robina Pereira; and a granddaughter.

Mr. Gray lived most of his life on the block opposite Gray’s Papaya and more recently in the garment district.

Rachael Gray helped run Gray’s Papaya and took over the place as her husband’s Alzheimer’s progressed. Tessa and Rufus, who are 18-year-old twins, are sometimes behind the counter, particularly during the summer.

As to the future, “Long live Gray’s Papaya,” Ms. Gray said in a phone interview. The store has a friendly relationship with its longtime landlords and years left on its lease, which the family plans to renew.