Where was he headed, that naked guy clambering his way through the crowd? The date was Dec. 6, 1969, and the place was the Altamont Speedway in Northern California.

Though there are many reasons to recall a moment when, as Rolling Stone described it, “everything went perfectly wrong’’ — a day when famous bands didn’t play; when bad acid felled dozens and scores more were injured; and when one of the Hell’s Angels hired to police the event knifed and killed a man during a Rolling Stones set — the image I return to is a peaceable one.

“What the hell was he doing?’’ said Bill Owens, the journalist who took the picture that appears on the cover of “Altamont 1969,” a book of previously unpublished photographs from the concert released in May. “He was just somebody that decided to take off his clothes and walk off into the distance.’’

Maybe he was headed for the future. The thought occurred to me as the 50th anniversary of Woodstock approached — it took place just four months before Altamont — and, with it, an inevitable torrent of images conjuring up a bygone era of peace-and-love.

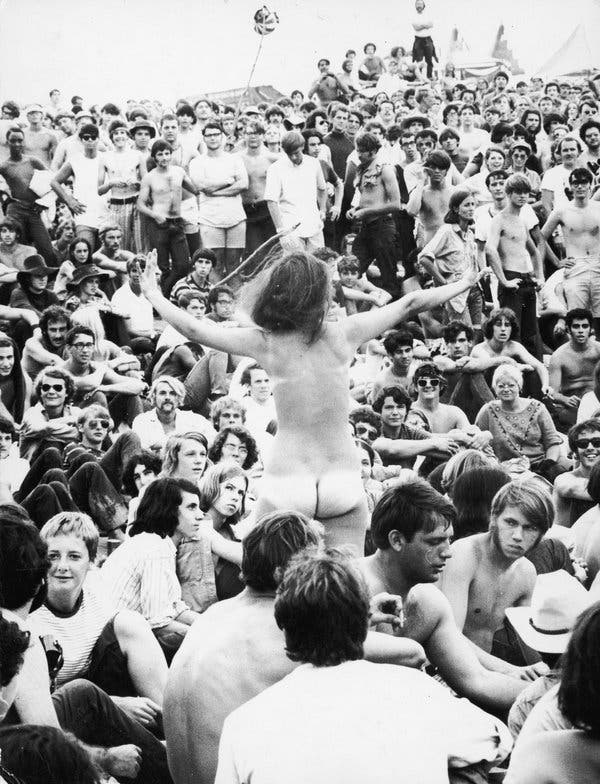

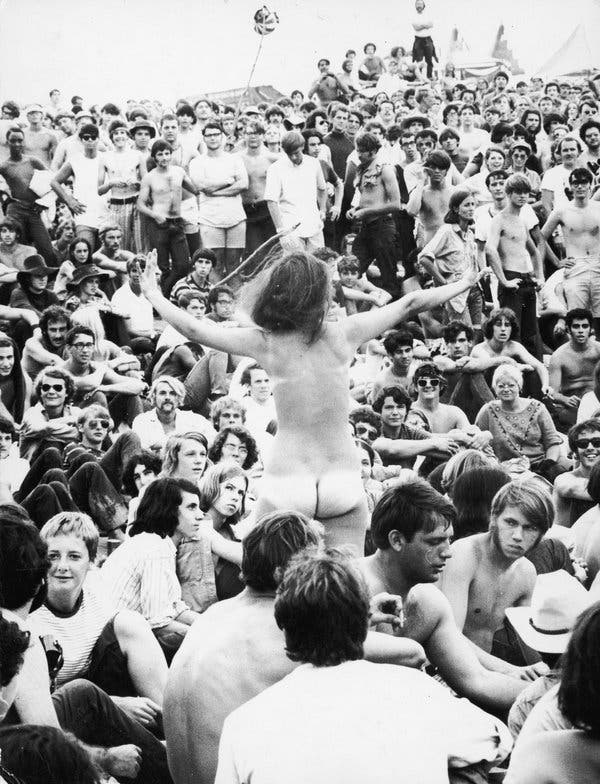

Many of those photographs depict people dressed as if for Eden. That is, they have no clothes. Yet nudity, as countless studies have demonstrated, is a socially constructed state; even undressed, we are clad in the body expectations of our place and time.

Looking at photographs from these two related and yet unalike events — one held over a soggy August weekend in upstate New York, the other on a mild winter Bay Area afternoon — some scattered observations came to this viewer about the subtle ways in which what a naked human looks like have shifted across a half-century and also about how we think about and gaze at one.

CreditArchive Photos/Getty Images

1. In 1969, Americans were, it would appear, much thinner — men and women equally. (That guy picking his way through the crowd at Altamont has not an ounce of body fat.) As it happens, this superficial impression is borne out by the available data, since in 1971 the average 19-year-old man weighed just 159.7 pounds, according to figures compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics, and the average woman 131. A hippie now at Woodstock 50 — if such existed and if a planned anniversary concert had not fallen apart — would have added an additional 14 pounds to his frame and a woman another 20.

2. Our surfaces in 1969 were remarkably innocent of visible markings. Scouring shots of people dancing, skinny dipping or wallowing in the mud at Woodstock, you would be hard-pressed to find a single kanji, butterfly or heart, let alone neck tattoos or bodysuits. By the time a Harris Poll would survey 2,225 adults, 46 years after the festival, three in 10 Americans had at least a single tattoo; among millennials representing an age cohort parallel to that of the average attendee at Woodstock, fully 47 percent were inked.

3. The women who would have been violating decency statutes by going topless at Woodstock in 1969 would now, in a majority of American states, be free to bare their nipples in public (although not, by and large, on Instagram). In fact, on Aug. 25 — just two Sundays after the Woodstock commemorations and one day before the more consequential anniversary of women obtaining to right to vote in the United States — a parade celebrating GoTopless Day in New York City will snake through the canyons of Midtown from West 58th Street to Bryant Park.

4. Genitals are an altogether different story. Modesty, of course, is legislated differently in every place and time. (In one era, for instance, French police arrested women on beaches for wearing body-baring bikinis and in a later one exploited modest body-concealing burkinis as a means of pitting constitutional secularism against freedom of religion.) What was so acceptable at Altamont — among the seated thousands captured in Bill Owen’s photograph, only a single person glances away from the stage at the bare-bottomed goofball headed who-knows-where — could be grounds for arrest on, say, the public beaches of Fire Island.

True, isolated renegades still flout the law in order to sunbathe naked on public beaches. But the expansive Woodstock-style encampments that once existed just past an invisible line of demarcation separating naturists and “textiles” on both Jones Beach and Fire Island essentially vanished after public nudity was banned at the national seashore in 2014.

5. Unprovable though this may be, in the many photographs of naked people taken at Woodstock, the subjects appear surprisingly un-self-conscious. They look as though they already understood what a researcher at the University of London would later determine, in a 2017 survey of 850 British people of all ages and ethnicities, to be the beneficial effects of group nudity on wholesome body image.

“Nudism makes us happier,’’ was the conclusion drawn by Dr. Keon West, the psychology professor who conducted the research. It certainly seemed to be that way at Woodstock, where folks disporting themselves with abandon looked truly, innocently at home in their bodies — or at the very least less tortured about their self-presentation than the average person taking a naked selfie in the bathroom mirror.

6. A personal truth intrudes here in the recognition that, in my own deep-seated Puritanism, I could never have been one of those naked people at Woodstock or Altamont or anywhere, really. It is true that once, while staying with a friend in the eye-blink town of Oakleyville on Fire Island, in a house whose previous guest had been the sometime naturist Greta Garbo, I went swimming with a group of pals who first removed their bathing suits and slung them, as was then the custom, around their necks. It did feel thrilling and slightly illicit and pleasurable, as everyone promised, that unfettered freedom of bobbing around naked in the ocean.

But if I am being honest, it felt much better afterward to get dressed.