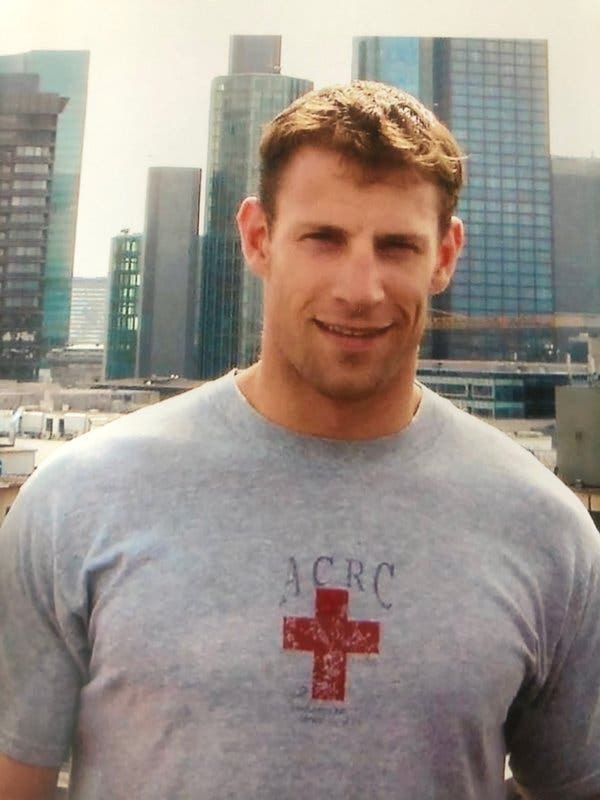

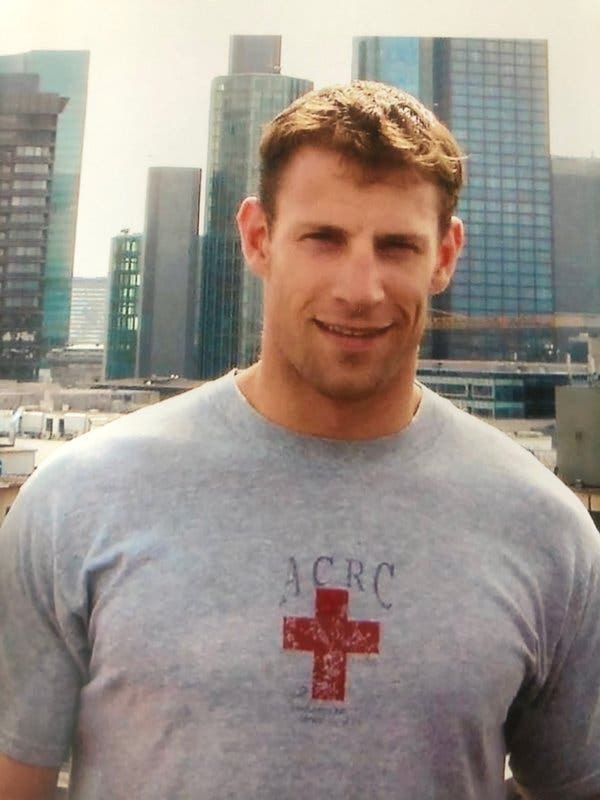

Suicide is the No. 1 killer of active-duty airmen in the United States Air Force. In February, the crisis prompted the Air Force to release a memo calling for a culture change within the service. For me and many others, that shift is a personal charge. Six years ago, my best friend, Neil Landsberg, died by suicide. Mentally and physically, he was the strongest person I knew. If he could kill himself, who else might be struggling? I spent years trying to make sense of this.

I should have seen the warning signs. I now recognize that Neil suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. He sought help from civilian mental-health providers and from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The civilian hospitals seemed completely unprepared in 2013 to help a combat veteran with PTSD, and the V.A. told him it could not enroll him because his medical records were not on file. He followed the V.A.’s application process, only to receive a letter denying him treatment because his income was too high. The letter arrived three weeks after Neil died.

[For more stories about the experiences and costs of war, sign up for the weekly At War newsletter.]

Neil and I first met when we attended the Air Force’s special-tactics officer-selection course as cadets in March 2002. Over five days, we performed countless push-ups, situps, squats and lunges. We covered dozens of miles, marching with 60-pound packs or running. We were subjected to a battery of psychological and intelligence assessments designed to test our problem-solving skills while under physical duress and no sleep. Those of us who passed faced 24 more months of specialized airborne, survival, combat diving and air-traffic-control training.

Toward the end of the course, we were instructed to pick up two 40-pound water cans and walk. We weren’t told how far; we were just told to heft the load and go. Unlike the rest of us, Neil didn’t hesitate. Off he went like Captain America, and he beat the rest of us by 400 meters. It would not be the last time Neil would make me feel inadequate. He was able to endure more physical pain than anyone I have ever met and quickly became known as the toughest guy in our class of cadets.

Neil completed his training a year before me and joined the 23rd Special Tactics Squadron. I was still wrapping up my training when an Iraqi Air Force plane crashed outside Baghdad, killing all five aboard, including three fellow special-tactics operators, whom we all knew. Neil shouldered the pain and wouldn’t talk about it. None of us brought it up, because we didn’t know how to deal with the loss. Back then, the military didn’t provide the mental-health resources that are available today, and we didn’t even know the terminology to describe what we were feeling. We were trained to be fighters, spending over two-thirds of the year away from home at military training ranges around the country. We were trained by combat veterans who were experts at their craft. Sparing no expense, we shot every weapon in the inventory and learned to field strip and rebuild our heavy weapons in the dark. We trained an average of six days a week for the entire eight months between deployments, then took just a couple of weeks of leave and deployed again. But no one was teaching us how to cope with the loss of our friends and colleagues.

In 2006, Neil and I deployed to Afghanistan. One of our airmen, nicknamed Surge, was on patrol in August 2006 when more than 100 insurgents pinned down two Special Forces teams and their Afghan counterparts in an ambush in Uruzgan Province. While Surge was directing nearby aircraft to target the attackers, he was killed by an airburst rocket-propelled grenade.

[Related: The first Marine in my battalion to die by suicide]

One of our airmen was assigned to pack up Surge’s personal effects and send them to Bagram Air Base to eventually be returned to his family. At Bagram, Neil decided we should burn Surge’s bloody body armor. We stood there holding it, and we talked about Surge’s death. Neil vented about how he felt responsible and helpless at the same time. He didn’t cry; he remained stoic as he spoke. We stared into the 55-gallon drum as we fed Surge’s body armor into its flames and talked about how Surge wasn’t required to be on this deployment. He had just returned to the United States from a deployment to Iraq with a separate unit, and he volunteered to take this trip to Afghanistan. Neil felt guilty for and hated the fact that we trained service members like Surge but then stayed behind while they were getting shot, blown up or killed.

When we returned from Afghanistan, I felt that Neil had lost his sense of purpose. He withdrew from his friends and colleagues and cared less about following the rules. He missed the flight home with the squadron and instead, without informing anyone, took a flight with a friend who was part of an aeromedical evacuation unit. He was given a letter of reprimand, but he didn’t care; he had already decided to separate from the service.

Back in the United States, Neil started to question the utility of everything we did. What was the point of prepping the guys for a war we aren’t winning? Neil’s loyalty to our operators never wavered, but he distrusted the broader military purpose behind what we were trying to accomplish in Iraq and Afghanistan. This sense of doubt ate away at him as his love for our comrades clashed with the brutal realities of combat.

In 2007, back in our stateside garrison at Hurlburt Field, Fla., Neil knew he was going to leave the military, but he didn’t have a plan for what to do next. I tried to encourage him to find a new purpose. We read books like “What Color Is Your Parachute?” and “Man’s Search for Meaning,” books that are supposed to help you clarify the big questions of your life: What is your “why,” and what do you value? They didn’t help Neil. I think he resisted the deep introspection required to let go of his experiences so that he could move forward.

Neil relocated to Washington, D.C., in pursuit of work that would be fulfilling and make use of his skills. Once in a while we would meet in Capitol Hill or Dupont Circle to catch up over beers. One afternoon we got together to watch the movie “300.” We talked about the brotherhood we shared and the men we lost and about trying to find meaning in our lives. He came to life when he talked about his visits as a volunteer to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and his work with Habitat for Humanity and Team Rubicon, a nonprofit that deploys veterans to do disaster response around the world. I thought Neil seemed to be doing better than he had in the Air Force, as though he had found his purpose again.

Around 2011, Neil began working for a military contractor supporting tactical intelligence and communications teams in Iraq. I was starting a family and still crisscrossing the Middle East with the Air Force. Our email exchanges became less frequent, and in the fall of 2012, while I was in Chicago attending graduate school, Neil stopped responding to me. That was unusual, but I figured he was busy.

What I didn’t know at the time was that Neil was suffering from PTSD. He hid his symptoms, but one time when the stress became severe, Neil told his brother, Matt: “I think I need to be checked in somewhere. I’m feeling suicidal.” Matt took him to a hospital, where a psychiatrist prescribed medication and sent Neil to another civilian hospital for observation. After four days, the hospital advised Neil’s family that he was well enough to be released. His family took him to a V.A. hospital so he could receive follow-on treatment, but they were told it would take weeks to enroll him in the system. In retrospect, the Landsberg family believes this is when Neil lost faith that he could be helped.

In May 2013, I was called by a mutual friend who told me Neil had killed himself. I was devastated. Confused. Angry. How could I have not picked up on his struggle? Why didn’t he confide in me or another friend? There was a service for Neil at Arlington National Cemetery. I told myself I couldn’t go because of final exams. But I know I leaned on that excuse to avoid my own guilt and grief.

A few months later, I forced myself to visit Neil at his final resting place in Arlington’s columbarium, where cremated remains are kept. His niche, and every other, is 11 inches wide, 14 inches high and 19 inches deep. Neil had been 6-foot-2, with a musclebound frame — incomparably greater than this tiny space in a wall. When I saw Neil’s name etched into the stone I cried for the first time. The guilt of not being aware of his inner struggle and my failure to intervene crushed me.

Today, I accept that I can’t change the actions that led up to Neil’s suicide, but I can control actions I take in the future. The Air Force is facing an alarming increase in suicides, with 2019 seeing a rise of about 50 percent compared to last year, and I want to do whatever I can to help do something about it. For instance, I recorded a podcast for the Air Force about losing Neil, as part of a push to teach people that it is normal and healthy to talk about stressors and to seek help. I’ve also had an active hand in the messaging for the recent Resilience Tactical Pause, the Air Force initiative that requires all airmen to stand down for a day to focus on mental well-being, resiliency and suicide prevention.

Neil was a respected operator, admired by his men for his approach to servant leadership, and an incredible human being. If someone that strong could succumb to the pressures of post-traumatic stress disorder, it could happen to anyone. In this sense, Neil is still leading all of us who served, admonishing us to be better for one another. I just wish I could be doing it with him, here, instead of doing it in his memory.