My patient had arrived from another hospital in the middle of the night. He was a wiry older man, restless but alert. He had a blood clot compressing the dominant hemisphere of his brain. He did not speak or move the right side of his body but fidgeted with his left hand and leg: pulling at his IV; removing his oxygen tubing and the ECG contacts pasted to his chest.

He did not seem to understand what was happening and could neither assent to nor refuse the surgery I was recommending. Yet just hours earlier, he had been his normal self.

His wife, whom I later learned was developing dementia, accompanied him in the ambulance. She was frail, thin and appeared disheveled and confused. She knew little about his medications and medical problems and didn’t know if he was on blood thinners. Still, given his rapid decline over a few hours, I took him to surgery. The craniotomy went well and he seemed to recover smoothly.

But my patient made little improvement over the next two days. A repeat CT scan showed that the blood I had removed had re-accumulated. This is a known complication of a craniotomy for subdural hematoma. Still, it felt like a personal failure. The easiest thing to do would have been to take my patient back to surgery. But was it the right thing to do?

Two weeks earlier I had attended a conference on palliative care held by the Archdiocese of Boston.

Dr. Mary Buss, a hematologist/oncologist and chief of palliative care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, related some recent research on moral distress in neurosurgery she had conducted with Dr. Stephen Miranda. Dr. Miranda, who was then a medical student and is now a neurosurgical resident at the University of Pennsylvania, interviewed neurosurgery residents about the decision to operate on an elderly patient with early dementia and on blood thinners with a subdural hematoma and a poor neurological exam.

A relatively simple surgery to open the skull and remove a blood clot compressing the brain can have dramatic effects. Many of my patients have made excellent recoveries, yet I have also treated many who never regained consciousness and ended their days in nursing homes, at worst unable to tend to their bodily needs, languishing in a comatose state between life and death.

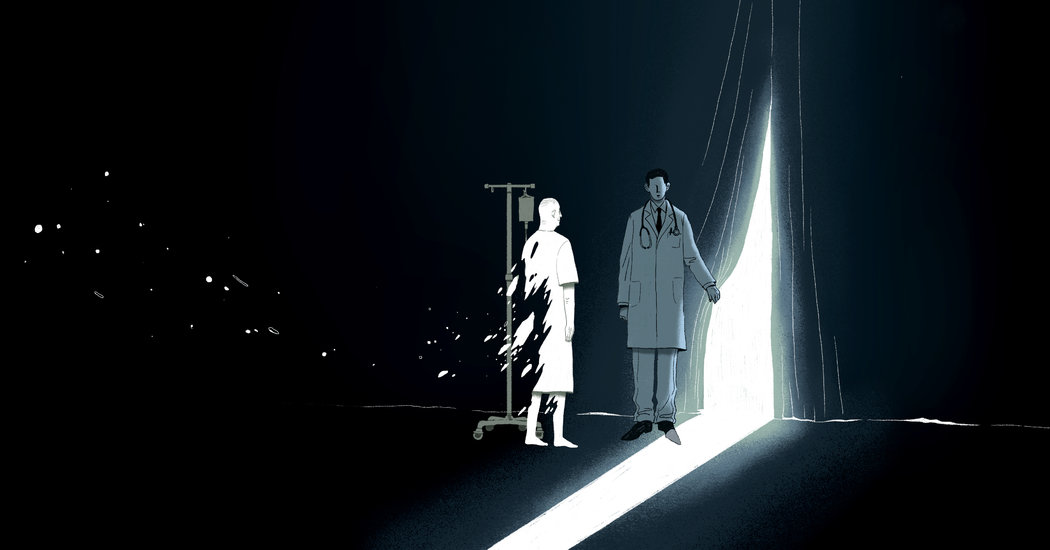

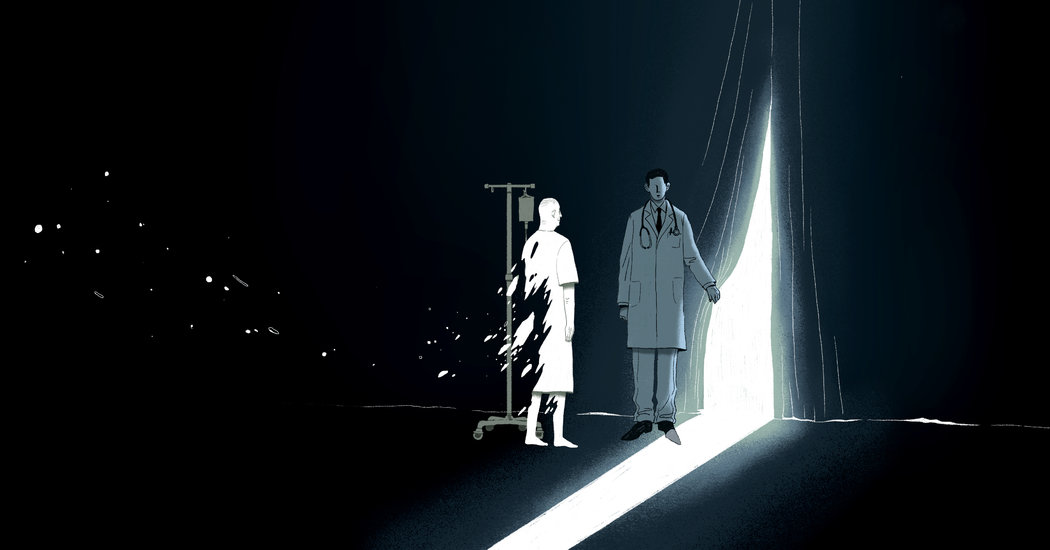

It is difficult to predict the outcome of this surgery, so the choice to operate or not to operate often generates moral distress in the doctor who makes it. A knowledgeable family who is available to speak on the patient’s behalf, or someone with a clearly articulated advance directive, helps guide us. But all too often, patients arrive by ambulance alone or families face these moments in crisis, contemplating death or disability in their family member as if for the first time.

I go with my gut when deciding whether or not to operate, but always, in the back of my mind, the circumstances stir up doubt. What if I’m wrong? Is it in the patient’s best interest to put him through surgery if the chance of meaningful recovery is vanishingly small? Yet, not taking this chance guarantees his death. The choice is laced with conflict and we make it on our own, often under intense time pressure because of the emergent nature of the crisis.

In Dr. Buss and Dr. Miranda’s research, fully 87 percent of respondents said they had participated in surgeries they disagreed with. When asked if the surgery was consistent with patient’s goals, almost a third replied: “I don’t know.”

Dr. Miranda said one resident commented: “Fewer people will question you if you do surgery, so surgery is the safe answer. A lot of neurosurgeons operate on the assumption that operating on 10 people is worth saving the one out of 10 people who do well after sustaining such an injury.” Another stated: “If people understand what’s going on, they make different decisions.” Given that older, sicker patients are less likely to do well in surgery than younger ones, fully 50 percent of residents felt uncomfortable performing this relatively simple surgery (for ethical rather than technical reasons).

Dr. Buss observed that surgeons are well trained in technical aspects of neurosurgery but poorly trained in communicating with patients and families. They have virtually no training in discussing the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments. These conversations often occur without supervision.

“Physicians,” she said, “are terrible in assessing their own communication skills,” noting that 30 percent of older adults die without the capacity to make decisions for themselves. When asked, 90 percent of patients document in advance directives their preferences to limit treatments. But physicians must ask.

This discussion resonated with me. It also provided me with a framework on which to base decision-making for future patients. Knowing that my colleagues struggle with the same doubts I do was reassuring and allowed me some needed perspective on my own decision-making and communication skills. It is crucial that we make decisions in the context of what matters to the patient and their family and that we understand as best we can their fears and hopes for the future.

With Dr. Buss’s recent talk fresh in my mind, I called and spoke to my patient’s daughter and son-in-law. Later, we all spoke with his wife. I explained that my patient had not improved much since his surgery and that, while we could remove the blood again, I was uncertain about whether he would regain independence. I had serious reservations about his future quality of life. His daughter told me that her father would not want this. He was fiercely independent and had also become the caregiver for his wife; she knew that her mother would not be able to manage the situation.

Over the course of a half-hour, it became clear to me that repeat surgery would not be in his interests and would, in fact, be a violation. We moved from this decision to discuss palliative and hospice care. His family wanted him to be comfortable and to be transferred closer to home. We all agreed that this was the best choice we could make for him at this moment.

At the end of our conversation, they thanked me for what I had done and for helping them make this choice on his behalf. Later, I consulted with the hospital’s palliative care team, which stepped in and did a masterful job of arranging for his transfer to an inpatient hospice unit at a hospital closer to the family’s home. This outcome — my patient’s death — although not what we had hoped for, felt right to all of us.

Only later did I realize that while I felt sadness, I no longer felt moral distress. That distress, which I felt acutely when I planned to take my patient back to surgery, had lifted. My feelings of guilt and failure had more to do with me than with my patient; a repeat surgery might have made me feel better, but would not have served his interests.

I moved from the disquiet of moral distress to a feeling of equanimity and to a sense of moral integrity. The insights I gained in connecting with my patient’s family will help me when, inevitably, I face similar situations in the future.

Joseph Stern is a neurosurgeon in Greensboro, N.C., who has written a memoir about the loss of his sister.