Grindr, the social networking app, sent a pop-up message about the risk of monkeypox to millions of European and American users. A sex party organizer in New York asked invitees to check themselves for lesions before showing up. And the organizers of the city’s main Pride celebrations posted a monkeypox notice Sunday on their Instagram account.

As hundreds of thousands of people gather in New York City and elsewhere to celebrate Pride this month, city and federal officials, health advocates and party organizers are rushing to disseminate an increasingly urgent health warning about the risk of monkeypox.

“Be aware, but don’t panic,” said Jason Cianciotto, the vice president of communications and policy at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, summing up the message the group is trying to convey.

The virus, long endemic in parts of Africa, is now transmitting globally, and, while it can infect anyone, at the moment it is spreading primarily through networks of men who have sex with men, officials say.

Since May 13, when the first case in the outbreak was reported in Europe, more than 2,000 people in 35 countries outside Africa have been diagnosed with the virus. As of Wednesday, there were 16 cases identified in New York City, among 84 around the country. The most recent New York cases are not linked to travel, suggesting person-to-person transmission is taking place in New York City, the city health department said.

While the raw numbers are still low, epidemiologists are concerned because of the level of global transmission and because cases are cropping up without clear links to one another, suggesting broader spread. The World Health Organization will be meeting next week to determine if monkeypox now qualifies as a global health emergency.

Monkeypox, so named because it was first discovered by European researchers in captive monkeys in 1958, can infect anyone, regardless of gender, age or sexual orientation. While it mostly spreads through direct contact with lesions, it can also be spread via shared objects such as towels, as well as by droplets emitted when speaking, coughing or sneezing.

Scientists believe it may also be transmitted through tiny aerosol particles, though that would probably require a long period of close contact. The virus in general is much less contagious than Covid-19.

Monkeypox has caused at least 72 deaths this year within African nations where the virus is endemic, the W.H.O. director general, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said Tuesday, but no other deaths have been linked definitively to the global outbreak outside Africa.

The first 10 cases in New York were all detected in men between ages 27 and 50, and most have identified as men who have sex with men, following the global pattern, according to the city health department. Most of the New York cases have resulted in mild symptoms, officials said, but even mild cases can involve an itchy and painful rash, lasting for two to four weeks.

Public awareness about the outbreak, which would lead to more demand for tests, is still at an early stage, and the virus sometimes causes only a few lesions in the genital area, which can make it difficult to differentiate from other sexually transmitted diseases. Two vaccines, as well as antivirals, are available, though for now vaccines are primarily being offered in America to close contacts of identified or suspected cases.

Pride celebrations are the perfect time to increase awareness among people in the L.G.B.T.Q. community who are most at risk, health officials said in interviews, but also create a challenge for those seeking to get out a message about protecting the community without creating alarm or stigma. More broadly, organizers and health officials do not want to put a damper on Pride celebrations and their positive messages about sexual identity.

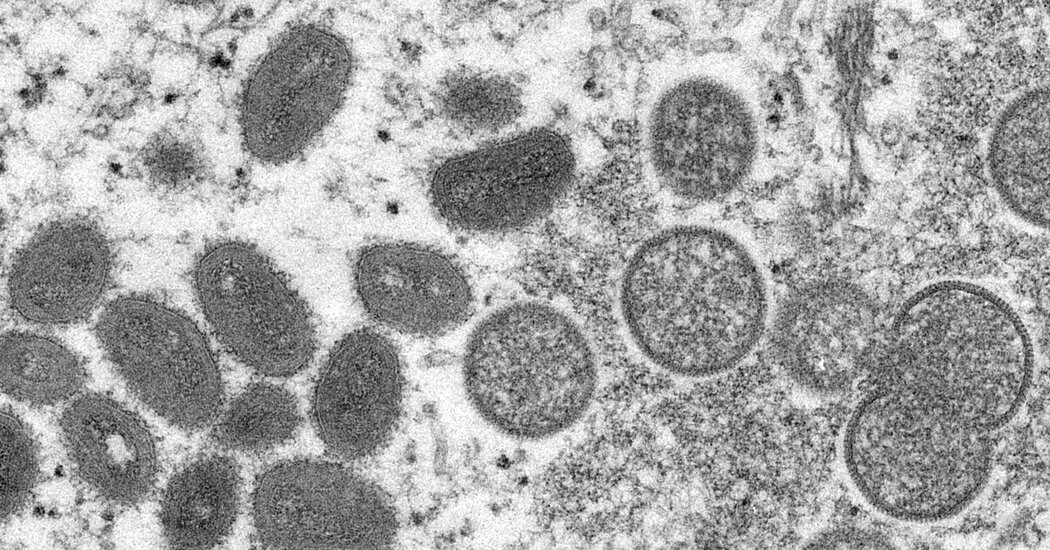

Working with advocates and partners in the L.G.B.T.Q. community, federal and local health officials have in recent weeks begun to craft social media posts, write fact sheets and post images of what the pox look like to help people know what to look for.

Pride gatherings also are coming at a crucial time, when there is still a chance that aggressive public health actions could keep monkeypox under control, but increased contact during the celebrations might create additional disease spread, particularly if people are not educated about the virus.

“We need everybody to step up their game, because if we’re going to contain it, we need a real ramping-up of efforts across the board,” said Gregg Gonsalves, a longtime AIDS activist and epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health, in an interview. “We’re walking the line between containment and persistent spread, and containment would be better.”

Health officials’ focus for now is to provide information about how the disease transmits — primarily through skin-to-skin contact — and to urge people to seek care if they have a rash or feel unwell. While the messages are targeted particularly to the gay and bisexual community, public health officials also stress that anyone can get infected.

Although the current risk for the general public remains low, it could rise if the virus establishes itself in the United States and other countries outside Africa, infecting a wider swath of people, the W.H.O. warned in a recent update. The organization is also working on changing the name of the virus, which they acknowledge may be increasing the stigma surrounding it.

Still, many health experts are warning that the public health messaging, which for now is mostly online, has to move quicker, and that education alone will not be enough to stem the outbreak.

All aspects of the monkeypox response — from education to identification of cases to isolating those infected — should be ramped up, said Dr. Carlos Del Rio, chair of the Department of Global Health at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University and the incoming president of the Infectious Disease Society of America.

“In order to contain this, we have to move quickly,” he said. “I wish we were doing more.”

Testing for the virus still remains rare in the United States. As of June 7, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had conducted 297 tests for the orthopoxvirus, the family of viruses to which the monkeypox belongs.

Public health experts warn that the C.D.C.’s centralized approach may be discouraging more widespread testing, creating echoes of the testing debacle that slowed down the nation’s response to Covid-19 in February 2020.

Testing currently happens in two stages: About 70 public health labs around the country are permitted to run an initial orthopoxvirus PCR test, but final diagnoses of monkeypox are made only by the C.D.C. lab in Atlanta. Commercial laboratories still cannot test for the virus. There is also no rapid, or antigen testing, for monkeypox, though one could be developed, as it was for Covid, said Dr. Jay Varma, the director of the Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response.

“Without meaning to make light of this, we have once again have been caught with our pants down by a global pandemic that we were not prepared for,” said Mark Harrington, the executive director of the Treatment Action Group and a long time AIDS activist, who urged improvements in testing at a monkeypox webinar hosted Monday by the Manhattan borough president.

Some aspects of the federal response have been praised by the L.G.B.T.Q. community. The C.D.C., for example, recently put out a sex-positive fact sheet on social gatherings and safer sex, which, rather than telling everyone to stay home, contains specific tips for avoiding monkeypox such as keeping clothes on during sex and not kissing.

“Some people are concerned that this is happening during Pride,” said Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, director of H.I.V./AIDS Prevention at the C.D.C. and a leader of the agency’s monkeypox response. “I can’t imagine a better time to get messages out about something like this.”

The parades and open-air events this month “are not where the virus will be spread,” Mr. Cianciotto of Gay Men’s Health Crisis said, so people should not be afraid to participate in them. “And as for clubs that are having parties that are having closer physical contact, or for people who are enjoying being with others in an intimate way, they need to get the information about what to look out for and how to get help.”

Still, as much as there has been a growing urgency about education, there has been less around scaling up other aspects of the response, such as increased access to testing and vaccination for those who consider themselves high risk, said Joseph Osmundson, a microbiologist at New York University who is among a group of gay and queer activists talking regularly with decision makers about the response.

He and other activists have also been working through their own channels to educate the L.G.B.T.Q. community about the virus — for example, by crafting messages that sex party promoters can distribute to attendees that include photos of monkeypox lesions.

“When I talk to my friends in the queer community, we want intervention,” Dr. Osmundson said. “We do not want monkeypox. The spaces where we meet for pleasure and companionship, we don’t want those to be shut down, number one. And we like going into those spaces with as little worry, and as little risk, as possible.”