Molly O’Neill, a freewheeling writer born into a family bent on raising baseball players who would transform herself from a chef into one of America’s leading chroniclers of food, died on Sunday in Manhattan. She was 66.

Her family said the cause was cancer; her long and public bout with the disease and with an earlier liver transplant was, in typical Molly O’Neill fashion, going to be the subject of her last book.

Ms. O’Neill ushered in an era of food writing in the 1990s that was as much about journalism as deliciousness, built on the work of writers like M. F. K. Fisher, Richard Olney, Elizabeth David and Craig Claiborne, the former food editor of The New York Times.

“I wanted to be all of them,” she wrote in 2003, “with a slice of Woodward and Bernstein on the side.”

Ms. O’Neill, who came of age when the seeds of the modern farm-to-table movement were being planted, became a keen observer of what she called the “essential tension in the American appetite,” which to her mirrored the conflicts in American culture. It was a tension between the refined and the lowbrow, the processed and the natural, “the civilized and the wild,” she wrote in “American Food Writing: An Anthology With Classic Recipes” (2009), which analyzed 250 years of American culinary history.

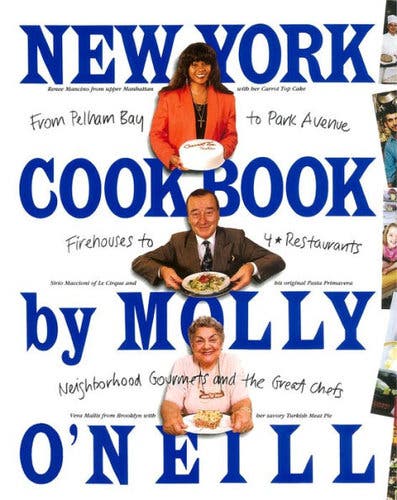

That book built off work she had done in “The New York Cookbook,” published in 1992. In that book, she explored the nooks and crannies of all five boroughs, bringing back tales of pierogi makers and grillers of Jamaican jerk chicken and stirrers of avgolemono soup. She included 500 recipes from the famous and the people who should have been famous, including roast chicken from the city’s four-star chefs, Katharine Hepburn’s brownies, Edna Lewis’s greens and Robert Motherwell’s brandade de morue.

“For more than 20 years I tried to tease the extraordinary from the mundane, and to use the familiar — the sprig of basil, the bottle of olive oil — to usher readers into social, geographic and cultural worlds where they otherwise might not go,” she wrote in The Columbia Journalism Review in 2003.

With American food writing today including many voices and cultures, it is easy to forget that Ms. O’Neill was doing so long before the globe-trotting Anthony Bourdain and the Los Angeles restaurant critic Jonathan Gold were household names, at least in food-centric households.

“This is exactly what Tony Bourdain was doing, and nobody gave her any credit for it,” said Ruth Reichl, the author and former Times restaurant critic.

Ms. O’Neill recalled her years growing up in Ohio in this 2006 memoir.Credit—

“She celebrated all kinds of cooks and articulated very clearly that cooking is what brings us together,” she added. “And she had no prejudice about whether this kind of food was better than that kind of food.”

Ms. O’Neill often wrote the kinds of stories that other food writers chased, like a 1992 article for The Times in which she observed that salsa was replacing ketchup as the king of the American condiments.

“To the food industry,” she wrote, “the rise of salsa symbolizes more than a growing gustatory sophistication. It is the death knell for the sort of cooking ketchup enhances.”

“I just remember reading that salsa piece and wanting to shoot myself,” Ms. Reichl said. “Why didn’t I think of that?”

A collection of Molly O’Neill recipes.

In her later years, Ms. O’Neill dedicated herself to teaching younger food writers. She taught classes online, held monthlong summer retreats and raucous weekend seminars at her property in Rensselaerville, N.Y., and opened her house to other teachers who might want to run a class on the power of making a good pie crust.

Ellen Gray, a baker and food writer, quit her job in 2014 to attend one of the summer writing sessions in Ms. O’Neill’s house. Like many of Ms. O’Neill’s students, Ms. Gray recalled her as a supportive but formidable teacher with a deep dedication to the craft of writing.

“She really taught that your notebook and your pencil — that was your instrument,” she said, “and you had to practice it every day.”

With Ms. O’Neill’s encouragement, Sara Kate Gillingham, a food writer and part-time neighbor in upstate New York, started the Dynamite Shop, a cooking school for young people in Brooklyn. Ms. O’Neill, she said, “seemed to eschew recipes and write from a guttural place, but it was because she understood the technicalities of food and words so well that she was able to wander off into this other zone.”

Molly O’Neill was born on Oct. 9, 1952, in Columbus, Ohio, to Charles and Virginia O’Neill. She was the only girl among five brothers. Her father worked at North American Aviation for a time and later had an excavation business; her mother sometimes worked in a hospital laboratory.

Baseball was a constant in Ms. O’Neill’s family: Her father was a minor league pitcher, and her brothers all played while growing up, though Paul, the youngest, was the only one to make a career of it, becoming a major league outfielder for the Cincinnati Reds and, from 1993 to 2001, the Yankees.

Columbus, Ms. O’Neill wrote in “Mostly True: A Memoir of Family, Food, and Baseball” (2006), was considered representative of average America by food chains, which liked to try out new products in the city. Some of her earliest culinary memories involve taste-testing, something she took very seriously.

For a 1992 book, Ms. O’Neill went on a culinary exploration of the nooks and crannies of all five boroughs of New York City.

“I never sported my carefree smile when tasting new products at the grocery store or standing in line for free samples at prototypes for Kentucky Fried Chicken, Krispy Kreme doughnuts or Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips,” she wrote. “No, on those occasions I would close my eyes and try to align my heart and mind with the rest of the country’s. I knew that millions of dollars, the taste of dinner and the future of the American landscape rested in my tongue.”

She cooked often for the family. That experience came in handy when, at 15, she began working at the restaurant of the Hospitality Motor Inn in Columbus. She continued working there after she enrolled at Denison University in nearby Granville. After earning a bachelor’s degree in 1975, she moved to Massachusetts and, in 1977, with eight other women, opened the Ain’t I a Wommon Club, which served “nonviolent cuisine,” as she put it in her memoir.

“In 1977,” she wrote, “it was still possible to learn how to run a little restaurant by opening one, and that is exactly what we did.”

The founders earnestly debated matters of feminism, Marxism and more, but Ms. O’Neill was the only one in the collective with actual kitchen experience. “I was eager to do the cooking so that those better qualified might have more time to talk about the cooking,” she wrote.

From there she moved to an Italian restaurant in Provincetown, on Cape Cod. In 1979 she enrolled in an eight-week course at the Paris cooking school La Varenne. Later that year she began working at Ciro’s, a well-regarded restaurant in Boston; in 1982 Boston Magazine named her “best chef, female” on its annual Best of Boston list.

She also began dabbling in writing, including for Boston Magazine. In 1985, when Don Forst, the editor of that magazine, became editor of the newly created New York Newsday, he hired her as its restaurant critic.

She moved to The Times in 1990 and wrote for the paper’s Sunday magazine and Style section for the next decade.

Her books included “A Well-Seasoned Appetite: Recipes From an American Kitchen” (1995), “The Pleasure of Your Company: How to Give a Dinner Party Without Losing Your Mind” (1997) and “One Big Table: A Portrait of American Cooking” (2010).

Ms. O’Neill’s marriages to Stanley Dry and Arthur Samuelson ended in divorce. She is survived by her mother and her brothers Mike, Pat, Kevin, Robert and Paul.

Ms. O’Neill was as transparent as anyone about her life, writing about her body image, her famous baseball-playing brother and her own self-doubt and fear when she was found to have a liver disease and, later, cancer.

Many in the food and writing community rallied around her, donating to a fund set up by the writer Anne Lamott to pay her medical bills. Her last book was to be about her illness and her liver transplant; she wanted to call it “Liver: A Love Story.”