This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email transcripts@nytimes.com with any questions.

- archived recording 1

-

Love now and forever.

- archived recording 2

-

Did you fall in love?

- archived recording 3

-

Just tell her I love her.

- archived recording 4

-

Love is stronger than anything.

- archived recording 5

-

[SIGHS]: For the love.

- archived recording 6

-

Love.

- archived recording 7

-

And I love you more than anything.

- archived recording 8

-

(SINGING) What is love?

- archived recording 9

-

Here’s to love.

- archived recording 10

-

Love.

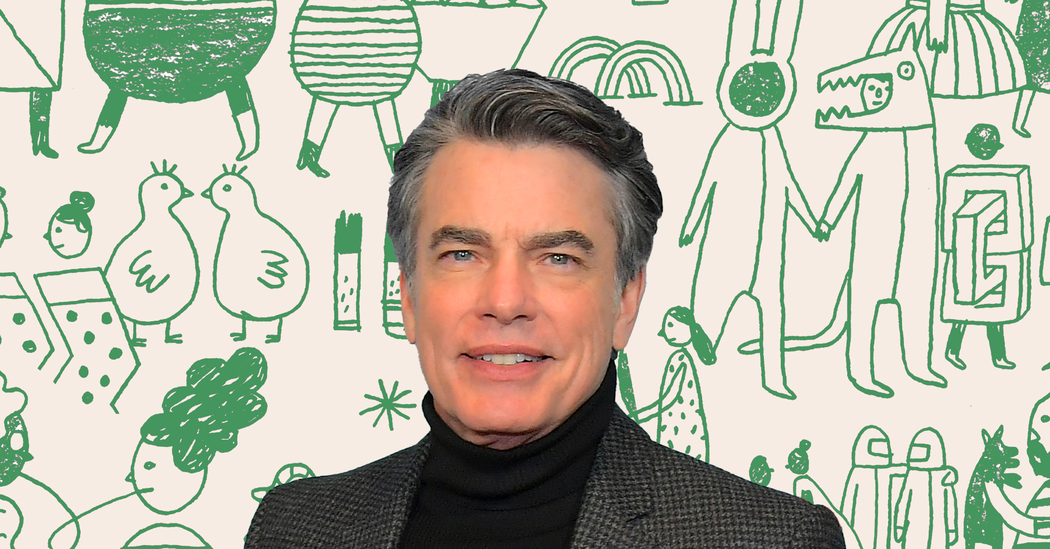

From “The New York Times,” I’m Anna Martin. This is “Modern Love.” Recently on the show, we’ve been celebrating 20 years of the “Modern Love” column, asking some of our favorite people to read essays that they connect to personally. Today, we’re closing out our season with actor Peter Gallagher.

Peter got famous mostly playing a particular kind of role — skeezy, cheating, lying men. That was back in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s in movies like “Sex, Lies and Videotape” and “American Beauty.” But if you missed that chapter of Peter’s career, you might associate him with a totally different kind of character.

To many younger fans, he’s Sandy Cohen, the loving, devoted dad and husband on the TV show, “The OC.” And now, having met Peter myself, I am very happy to report that Peter is way more like Sandy than his other roles. It’s just so clear he really loves his family. He showed me his phone background when he came into the studio. It’s a photo of his wife, Paula Harwood, from when they first met. And if you look him up, his Instagram is a total dad Instagram, full of long captions bragging about his kids and cute selfies with Paula. And it just so happened that the very day Peter and I spoke was his and Paula’s 41st wedding anniversary.

So, today, Peter reads the essay, “Failing in Marriage Does Not Mean Failing at Marriage,” by Joe Blair. And as I talked to Peter about his own relationship, I started to understand what’s kept it going for so long.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Peter Gallagher, welcome to “Modern Love,” or should I say welcome back to “Modern Love“?

Well, thank you very much, Anna.

It is a total pleasure to have you here. You read an essay for us back in 2017. Now you’re here again. And Peter, I heard that today, this very day we’re talking, is your 41st wedding anniversary?

God, it sounds so embarrassing when you’re in show business, but yes, it’s true.

I’ve read in interviews where you say that it’s embarrassing to be together for 41 years, but tell me what you mean by that.

Just that it’s not something you hear every day, and it’s not something I ever really am interested in promoting because I always feel like that people say, oh, you know how long we’ve been married? And then they do it in the press, and then six months later, they’re on the rocks.

But you don’t want to jinx it, is what you’re saying?

Well, not jinx it. It’s just, I do think it’s dangerous to, like, promote it or talk about it. It’s not immutable. It’s a living, breathing thing.

Oh, I see what you’re saying.

Something that needs to be — it’s like, it’s a garden.

I love that. Well, congratulations again.

Thank you.

Tell me what at 41 years, what comes to mind when you think of 41 years?

Holy shit.

It’s just astounding, really, because I don’t think either of us feel substantially different or changed. Of course, we probably are. And I feel very lucky about it. I feel very lucky about it.

Do you have any advice for people who are hoping to make it that long in their marriage?

Don’t get divorced.

There you go. Straightforward, yeah. Anything else?

Good luck.

[LAUGHS]:

Well, the fact is, it’s, you know, I find there’s very little certainty about anything in life. So much of life, including love and work and the choices you make, is built more on suspicion than certainty. And it’s being able to listen to those subterranean streams that are talking to you, and you kind of hope you’re going in the right direction. But there’s very little certainty, I think.

Picking up on the signs, the signs that this is something worth holding on to.

Yes, and being willing to cope and accept the uncertainty of it anyway.

Yeah, I like what you’re saying, listening to the subterranean streams, as you call them, trusting your gut. It’s making me think of a story I heard about how you met your wife, Paula. You met her your first week of college at Tufts University on a stairwell —

God, you’ve been doing research.

Well, there you go. You gotta do it for the job.

Oh, my God. This is the New York Times building. Of course you have been. [LAUGHS]

Can you tell me a bit about that story? I love that image, meeting on the stairwell. Tell me how you first saw her.

OK, it was our first week of freshman year in college. And —

How old were you? 18?

Yeah.

Wow.

Yeah. Oh, wow. That means we’ve — whoa. We’ve known each other for a very long time. I think it was September 13.

Wow.

We think that it was September 13.

OK.

It was at Bush Hall at Tufts University. And I was going up the stairs to see a girl, and she was coming down the stairs to see a boy.

[LAUGHS]:

And no words were exchanged. And I don’t remember anything about anything, but I remember almost every moment of that. And we just sort of glided by each other. She was in this spectacular hair and this tight turtleneck thing and a disco belt and tight corduroy bell bottoms and platform shoes.

OK, gorgeous.

And I looked like I had just left eighth grade gym class or something like that. Yeah, she was way, way, way, way, way cooler than I am — still. And it was just powerful. And I spent the next seven years trying to figure out how I could go out with her.

Oh. I was going to say, so you were both going to see other dates, let’s say. You clearly remember what she was wearing. You remember. Tell me a little bit more about that feeling that you remember. Was it like a, “I’ve known you before, even though I don’t“? What was that feeling for you?

I was just kind of surprised at the feeling.

Hmm.

I had never really felt anything like that. I found her in this freshman yearbook, and I would look at her picture and I’d think, wow — as being someone unattainable, you know, as, wow. And yeah, it was weird.

When was the first time you talked to her? Do you remember that?

Probably a few years later. No.

[LAUGHS]:

I was pretty dweeby.

Aw.

No, what I did was, I would — well, regardless of my class schedule, I would manage to be in the cafeteria for lunch when she was.

Aw.

And so I would make her laugh. And frankly, that’s still, like, a huge component of our relationship.

Mm. Was there a — I don’t know — like, how far into the relationship did you think to yourself, like, I want to marry this person? Was there a moment?

[CHUCKLING]: We were driving up to Boston to see a friend of hers who was the first person I ever knew who was getting married that was our age. And it was a torrential rainstorm. It was torrential. It was sheets of water were coming onto the windshield and so on and so forth. And we were talking about going up to this wedding.

And then — and this is not a moment I’m proud of, but it was true — I started to say, so, wow. Like, well, yeah, Ron is getting married. Well, whoa. Hey, that’s something that a lot of people do.

Maybe — could you ever imagine that kind of thing, doing something like that with somebody like me, or something like that?

Oh!

Meanwhile, we’re driving in this torrential rain.

Right.

And as I’m saying this, she says, what are you asking me? Well, I’m asking — are you asking me to marry you? Well, well, well, it certainly seems that way. And —

[LAUGHS]:

She said, are you gonna ask my parents? Uh, well, yeah. [LAUGHS]

No!

Then I did. And then I wrote her dad a long letter about how I would take care of her. And he didn’t have to worry. And we got married.

And here you are now, Peter, 41 years later. OK, so the “Modern Love” essay you chose to read today is about a marriage that lasts, but not without some serious hurdles along the way. It’s written by Joe Blair, and it’s called “Failing in Marriage Does Not Mean Failing at Marriage.” Peter, what did you see in this essay that drew you to it?

I felt like they loved each other. And regardless of the ways in which Joe may have felt he failed in his marriage, I think we all do, to some extent. It might be more dramatic or less dramatic, but there’s always that sense of what you’re not getting or what you’re not giving or what you should be getting or what you should be giving.

And ultimately, I think it has very little to do with love or marriage. I think you hope to get to a place where you sort of embrace the whole person, not what they’ve done for me lately or what they haven’t. But start to appreciate with some gratitude the fact that they occupy such an important part of your life and you theirs and somebody you can trust.

Mm. What a beautiful way to lead us into this essay. Why don’t you take it away for us whenever you’re ready?

“Failing in Marriage Does Not Mean Failing at Marriage,” by Joe Blair.

“Alone one evening in early spring, seated on a green park bench beside the Charles River in Cambridge, Mass, I waited for Deb.

The sun was setting and the temperature was falling, and I was wearing my softball jersey and knickers and wishing I had remembered to bring my thick flannel shirt.

Now, decades later, at my home in Iowa, I search for that bench on Google Maps. Here it is, Riverbend Park. Here’s the bridge, the John W. Weeks bridge. Here’s our bench. The bridge arches. The still water. It makes my body ache to see it again. The place where we were young.

We had agreed to meet there in that ratty little park. I waited for her and waited. I imagined her getting off work at Legal Seafoods at the Copley Plaza, cashing out, boarding the bus, walking along the path, approaching.

I imagined someone watching us as she arrived. Would they think we were madly in love? Mistake us for Harvard students, people with illustrious futures? The moon was brightening. The sun, a slur of color in the west. I was cold. My thick flannel shirt at home in my closet.

I had returned to college at 26 after serving my apprenticeship in the refrigeration trade. I first noticed her in my selected authors class. On the first day, the professor asked if anyone could give him an Emerson quote, and she, blushing, raised her hand. Three months later, I asked her to marry me. She said yes.

We shared my tiny, overheated Cambridge apartment and fell into a nightly bar crawl routine, from The Plough and Stars to The Cellar, to Drumlin’s, The Cantab. After the first three rounds, I would accuse her of being in love with her cigarettes, and she would accuse me of not being truly in love with her. And I would swear on the Bible how I loved her with the intensity of 10 suns while holding up my hand to order another round. We knew we needed to end this childish routine. We imagined a new town, unsullied by the likes of us, someplace clean and innocent.

After less than a year of squirreling away cash in a mason jar atop the refrigerator, we allowed the lease to expire, moved our furniture, a futon, and a lamp to the curb, paid our parking tickets, climbed on my motorcycle, and with no ultimate destination in mind, left town. We had enough cash left by the time we rolled into Iowa to run a small brick house adjacent to a hog farrowing pen on the rolling Iowa cornfields. Soon, we found work and started a family.

By the time Deb kicked me out for the first time, she had already given birth to our first two children. I moved into a duplex on East Washington in Iowa City. The inside of the place reminded me of a rustic hunting lodge. The shiplap walls and ceilings were stained dark brown. I remember sliding into my Coleman’s sleeping bag that first night, settling myself on my camping mat and thinking, ah, yes, this is how I’m meant to be — alone.

We reunited after a month or two. Then we had the twins. Saturday nights, we would walk down to George’s, where, three beers in, Deb would once again accuse me of not loving her enough. And I would do my best to drum up the old enthusiasm. But I wasn’t fooling either of us.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Over the 32 years of our marriage, she has kicked me out five times. One time, I sublet a basement apartment across the street from a small park with a basketball court, which was a big plus. The basement was crawling with little white worms, which, when they died, curled up like pill bugs.

Another time, I moved into Le Chateau, a low-rent apartment complex. There was an outdoor pool on the property, but it wasn’t open when I lived there. I don’t think it had been open for a long time, hence the black mud and leaves at the bottom. There was a laundry room, which was my favorite room in the place. A single coin-operated washing machine and a single dryer. It was always warm and brightly lit, and there was a metal folding chair. And the air always smelled clean.

The last time, the sixth, Deb didn’t kick me out — I left. Weary of our accusation and outrage routine, I rented another duplex in a quiet neighborhood on the South Side of Iowa City. I shared the place with little red ants. They really liked the sponge I used to clean my dishes. I would boil water and soak my sponge in it to kill them, then dump the floaters down the drain.

I didn’t do anything in this apartment — didn’t cook, read or listen to music. If I got home from work early, I would go to bed. If I got home late, I would go to bed. I would lie down under my blue and white duck blanket, turn on my side, and think, yes, this is how I’m meant to be.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

According to the landlord, the young woman who lived there before me had once dated the young man who lived across the street with his parents. After she broke it off, the young man continued texting her. He even knocked on her door at odd hours. When the young woman moved out, I moved in.

Sometimes when it was dark, I would look through my front window at that house and think about the young man. I would wonder how one is supposed to find love, where to look, how to begin.

On weekend mornings, I took walks around the neighborhood. It was still cool enough to need a hat and a jacket. One of my neighbors had erected a book exchange. I chose a collection of Kafka’s short stories, and then, later that day, sat on my front cinderblock steps and began reading it.

But I kept thinking of Deb. I kept thinking how she would like this quiet, working-class neighborhood, with the book exchange and the red ants, and the Sycamore movie theater close enough to walk, and no traffic sound, and big deciduous trees, and rickety front steps, and cool air, and warm sun.

I called her and asked her if she wanted to stop over for coffee. We sat at my little kitchen table and drank our coffee. She said she liked my little house. She liked my rickety front steps.

I have always thought of Deb, wherever I am, whomever I am with, whenever I experience something good. I want her to experience the same thing. I can’t stand to watch a good movie without her. I’ll walk out after half an hour if I can’t turn to her in the dark and whisper, isn’t this great?

I can’t ride my motorcycle up into the Rocky Mountains. I can’t enter a small diner with the worn pine floorboards and an antique curved glass pie case with slices of banana cream inside. I can’t take a flight without wishing she were occupying the seat beside me.

I think we have the wrong idea about marriage. It’s not like running a business, where there are recordable credits and debits, or buying a house, where you pay your mortgage or lose it, or owning a pet, where, in return for companionship, you are obligated to feed them and take them for walks and clean up after them.

It’s more like learning, after 1,000 hangovers, to stop drinking so much, or learning, after often being false, to be true just once in the hope that you can continue to be true, or learning, after habitually hating yourself, to love yourself just once in the hope that you can continue to love yourself, and then learning, through loving yourself, to love someone else.

I will always love Deb, even when she hates me, even when I hate her. Not because she’s especially forgiving or pretty or pleasant to be with or well-read or spiritual. Not because she may or may not be any of those things. Loving her isn’t transactional. I love her because I can’t help it. There’s something in her that makes me weak, something vulnerable and unconquerable, something fleeting and unmoving.

After a few months in the house with the rickety steps, I moved back in with Deb. Soon enough now, I’ll be alone on the edge of sleep, just as I am alone on the edge of all things. It’s how I am. It may be how we all are. Still alone, waiting, and still in love.”

Peter, thank you. What came up for you as you read this?

I think it’s true. There’s a power and a truth to this and a humanness to this. I feel like I was with Joe where he was and the places he described so well. But it was sympathetic with where I was inside about how I feel about Paula, my wife.

More from Peter Gallagher after the break.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Peter, you just read the “Modern Love” essay, “Failing in Marriage Does Not Mean Failing at Marriage” by Joe Blair. And I want to hone in on something Joe Blair writes about his wife. He says, “I love her because I can’t help it.” Have you experienced that with your wife, Paula, or have you seen that in other areas of your life?

I experience it all the time.

Hmm.

I remember when I was growing up, I was really trying to encourage my father and my mother to split up because it would just be so much quieter and so much more peaceful. And it’s — Dad, I’d spend some time with you, spend some time with Mom. It’d be fine.

Then years later, probably 20 years later, I remember seeing my mother and father holding hands, walking, holding hands and really meaning it. And I thought, kids don’t know everything. And always, again, it encouraged me to believe that there was more to life, to love, to them, to us, than met the eye.

And all those halcyon moments when you can abandon the scorekeeping and abandon the transactions and begin to see just how lucky you are to be with this whole, complete, complicated person, good things seem to happen then.

I mean, I love that story, seeing them holding hands and realizing what you didn’t know when you were a kid, what you didn’t understand. But perhaps also another lesson is sticking it out. Does that feel like a —

Oh, yeah, that’s, I guess, what I — yes, thank you. That’s what I felt when I saw them, was that there is the potential for some grace —

I love that.

— by virtue of just sticking it out, sticking together.

To return to Joe Blair’s essay, I think what jumps out to me is how — and we’ve talked about this a bit, but how he redefines what a marriage is. He says it’s not like a business to maintain. It’s not like caring for a pet, which we hope not. It’s actually about learning to love yourself, so you can more fully love the other person. Can I ask you, why do you think that is? What is it about loving ourselves that allows us to love other people?

Well, I think it begins with forgiveness. I think you have to begin to forgive yourself because it can be like being a drunk, the desire for some kind of self-abnegation or constant expression of disdain against one’s self. And it takes courage to see things differently and to try to see things differently and believe it.

But I think that exercising that muscle of forgiving yourself for whatever imagined sins and crimes you’ve committed against humanity or yourself, it sheds enough light for you to be able to be generous and to see what’s there, not what’s not there.

Can you think of an example in your own life where loving yourself was key to being able to love your wife?

I just had a funny — I don’t know if it’s related, but I just flashed on this where I broke up with Paula once.

[GASPS]:

And I told my mom.

When you were dating her?

Yeah, we were dating. And I didn’t bring many people to my house when I was growing up, ever. But I brought Paula. And I told my mother. I said, yeah, I’m just breaking up with her. You go back to her and apologize.

[LAUGHS]:

She is a wonderful young woman. And any problem you’re going to be having with her, you will be having with anyone because they’re your problems.

Whoa.

So you be damn sure that you’ve figured out what’s going on with you before you start changing partners like socks. I don’t think she said socks, but she said that was the gist of it. Before you throw this relationship away, you investigate what it is that’s really bugging you. And I bet you’ll find it. It’s your issue, an issue that you will have, regardless of who you’re with. And I went, OK.

[LAUGHS]:

You know, all right.

She says the most wise thing. As a son, you’re like, OK, Mom. Yeah.

OK.

[LAUGHS]: But did you follow her advice? Did you look inwards and repair things?

Yeah, but it took me 30, 35 years. I didn’t want to give my mother the satisfaction while she was alive of doing it.

[LAUGHS]: Of course. It’s interesting. We’re talking about the kind of ups and downs of a marriage and even the time leading up to marriage. And certainly, Joe writes about all of the ups and downs he’s been through in his relationship. And despite that, the word “divorce” never comes up —

Oh, that’s true.

— in this essay, which is —

That’s interesting.

— very interesting. I guess I wonder, it comes down to Joe, throughout this essay, is sort of working out whether or not his relationship is working, right? Whether or not to keep going, to stay committed or whether or not to call it. And I guess I wonder — and I’m asking you for a lot of advice. I’m not even married, but I guess I am turning to you as someone who’s been married now for 41 years. Like, how do you make that call? How do you know if something is working. How do you know whether to keep fighting for something?

That’s what I mean about suspicion. There’s very little certainty. It’s like faith. It’s like willing to accept how little you might know and trying to pay attention to your partner and in a more inclusive view.

Can I ask, what does a successful marriage look like for you and Paula?

Well, we woke up on this beautiful day —

Mm. It is gorgeous.

— in this wonderful city. And we found just about everything funny. And she laughed. She had a lightness. I just felt very lucky.

Peter, thank you so much for today.

Oh, thank you. And it was a lot of fun.

And I cannot believe that we scheduled it on your wedding anniversary. That is really —

I was kidding about today being our wedding anniversary.

Are you serious?

No, I’m just kidding.

Oh, my God.

No, really.

Don’t scare me.

Yeah, no, no, no.

We’ll get the research team on this. We’ll get our fact-checker.

It’s real.

But seriously.

It’s real.

It’s real.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

That’s it for this season of “Modern Love.” Thank you so much for listening. We’ll be back this fall with more love stories.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

“Modern Love” is produced by Christina Djossa, Reva Goldberg, Davis Land, and Emily Lang. It’s edited by our executive producer, Jen Poyant, Reva Goldberg, and Davis Land. The “Modern Love” theme music is by Dan Powell. Original music by Dan Powell, Pat McCusker, and Rowan Niemisto.

This episode was mixed by Daniel Ramirez. Our show was recorded by Maddy Masiello and Nick Pittman. Digital production by Mahima Chablani and Nell Gallogly. The “Modern Love” column is edited by Daniel Jones. Miya Lee is the editor of “Modern Love” projects. I’m Anna Martin. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]