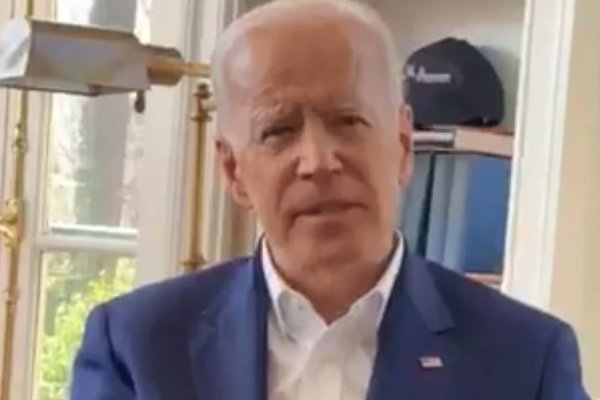

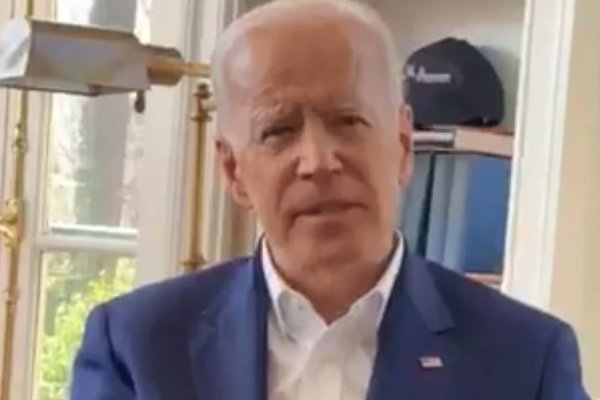

On Thursday afternoon, former vice president and potential presidential candidate Joe Biden released a video in which he discussed the importance of personal space. “Social norms have begun to change,” he said. “They’ve shifted, and boundaries of protecting personal space have been reset — and I get it.”

Mr. Biden was responding to allegations by two women that he made them uncomfortable by coming too close, and by being too familiar and hands-on. His video was, in part, an acknowledgment that the rules of social engagement can change over time — along with perceptions of how much physical contact is appropriate, and where the boundaries of personal space lie.

The dynamics of both social space and touching have been well explored by scientists. In the 1960s, American anthropologist Edward Hall laid out the basics of social space, based on field work in Europe, Asia and elsewhere.

We each reserve around us a zone of about 18 inches — “intimate space,” he called it — for close friends and family. “Personal space,” from 18 inches to about 4 feet, is open to acquaintances and colleagues. And “social space,” from 4 feet to 12 feet, is the appropriate orbit for strangers or new colleagues.

These zones appear to be wired into the brain’s evolved sense of spatial safety. Brain regions such as the amygdala, which registers threats, activate automatically when a boundary has been crossed.

In 2009, brain scientists at the California Institute of Technology reported the case of a woman with a genetic condition that had badly damaged her amygdala. Her social space was a fraction of the normal range, and strangers could approach within a foot and not provoke discomfort.

Those zones are averages, and they vary by individual, by culture and, likely, over generations. In some South American countries, such as Argentina and Peru, strangers are allowed a closer approach, and social space is more like 2 feet. Personal experience matters, too; someone who has been subjected to harassment or violence may well monitor the borders of contact more closely.

Mr. Biden, a temperamentally affectionate politician, plowed right into the intimate space of people he encountered, at a time, in the #MeToo era, when the discussion of inappropriate contact has gained volume and the need to acknowledge consent has grown acute.

People who develop a hands-on style, who are free with hugs and touches, generally do so because they have learned what a powerful bonding mechanism such nonverbal communication can be. In just the past decade, psychologists have conducted scores of studies on the effects of touching.

“Touch is the basic language of affection,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “It is one of most reassuring modes of communication. An embrace or encouraging shoulder nudge from the right person is more powerful than words in relieving anxiety.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Even small touches from lovers or friends have a powerful effect on the brain and body, instantly reducing physical signs of stress, and activating areas of the brain known to be involved in tamping down fear and anxiety.

Perhaps the most dramatic example comes from work led by James A. Coan, a psychologist at the University of Virginia, who has tested how hand-holding affects the anticipation of an electric shock.

In a 2017 study, a team led by Dr. Coan and Karen Hasselmo, of the University of Arizona, recruited 110 men and women of diverse backgrounds. Each was paired with a spouse, a lover or a friend, and was seated in an M.R.I. scanner with electrodes on an ankle, prepared for a slight electric shock.

The research team measured each subject’s levels of physiological distress and brain activity under several conditions, including while holding the hand of the friend or partner, while holding a stranger’s hand, and while facing the shock alone.

“The main finding on partnered hand-holding is that, when someone close to you is holding your hand, your reaction to the threat of electric shock is much lower” than when alone, said Dr. Coan. “Hand-holding from a stranger had no effect.”

Cross-cultural surveys have shown that almost any touch from a lover is agreeable, as are many expressions of physical contact from a friend. But, universally, strangers are allowed to do little more than touch a person’s hands. Contact most anywhere else is off-limits; the touch is received uncertainly, or as an intrusion.

The accusations against Mr. Biden seem to describe situations that fall somewhere between those extremes. The news coverage has put many women in mind of unsolicited shoulder massages at the office, or unasked-for hugs and arms around the shoulder. The touchers aren’t strangers; they are familiar colleagues, often valued ones, and not always men.

“My sense is that the first reaction of women who are touched in the workplace without invitation is what teenagers these days call ‘cringy,’” said Laura Kray, a professor at U.C. Berkeley’s school of business, in an email. “Not only is it uncomfortable, but it generates a kind of a panic at the thought of what is to come next, and how we are going to navigate this tricky situation.”

She added: “Obviously, having an established relationship of trust alters the meaning of an appreciative hug or a pat on the shoulder in a more positive direction. Arm around lower back or kiss on head are boundary violations, as a general rule.”

One question with no clear answer is how supportive touching gradually becomes more affectionate and, for some people, sexual and mutual.

“What we don’t know after all this time is how you get from one place to the other,” Dr. Coan said. “Nobody does. There’s no simple answer, in psychological research or in life. That trajectory is going to include all kinds of signaling errors. As people zigzag toward love or affection, they’re blowing it all the time.”

A blank stare, a cold shoulder, or a few flinty words can correct many, perhaps most, of those errors. But far from all of them — in part because of vast differences in the way individuals perceive touches from colleagues or co-workers.

For instance, research suggests that young children typically are encouraged and reassured by a friendly touch on the shoulder, not only from parents but also teachers. But that uniformity changes by young adulthood.

Some people recoil at any touch intended as affectionate that does not come from someone close; others can find the same touch, in the same circumstances, a comfort.

A similar variability likely exists among those doing the touching. A 2012 study led by Paul Piff of the University of California, Irvine, and Amanda Purcell of Yale found that people prone to hypomania, who are highly energetic and social, were exquisitely tuned to the comfort from touches intended to be supportive.

But there was a catch: They also were measurably numbed to intrusive or brusque touches. The research suggests that such people, by extension, also may be oblivious to the effect of their attempts at physical contact, and perhaps blind to the cringes of someone they’re trying to reassure or support.

Placing an arm around the shoulders of the wrong co-worker can invite a push, a slap, a formal grievance — or a viral video.

However the allegations against Mr. Biden play out politically or in the press, the boundaries of personal space will always remain somewhat fluid and, except in the most obvious cases, open to interpretation. If you aren’t sure, ask first.