Michou, a flamboyant fixture of the Parisian demimonde who ran France’s most celebrated drag cabaret for more than a half-century, died on Sunday night in a hospital in Saint-Mandé, a suburb of Paris. He was 88.

The cause was a pulmonary embolism, said François Deblaye, Michou’s press representative. “He hadn’t been able to breathe very well for a while,” he said. Last year, Michou was treated for colon cancer, which was said to be in remission.

It was in 1956 that Michou — born Michel Georges Alfred Catty — opened his tiny jewel box of a nightclub at the foot of Montmartre, the storied Paris neighborhood known for its nightclubs and connection with artists like Picasso and Toulouse-Lautrec.

Dressed habitually in blue, with a snowy white coif, manicured fingernails, a perpetually wide smile and a glass of Champagne always in hand, Michou was instantly recognizable in France, in part from his many television appearances. His death was front page news in France.

The Élysée Palace issued an unusually long statement on Monday lamenting his death, saying in part, “The sky above Montmartre will be a little less blue from now on.”

In Montmartre he was known for holding free luncheons for elderly residents. Cafes there engraved his name on plaques on his favorite seats, permanently reserving them for him. Local residents often blew kisses at him as he walked to his cabaret from his apartment overlooking Sacre Coeur, the basilica at the heart of Montmartre.

“They call me the ‘Blue Prince of Montmartre,’” Michou told The New York Times in an interview last March. (Even his home was decorated entirely in shades of blue, right down to a turquoise toilet seat.) “Around here, I’m treated like a saint.”

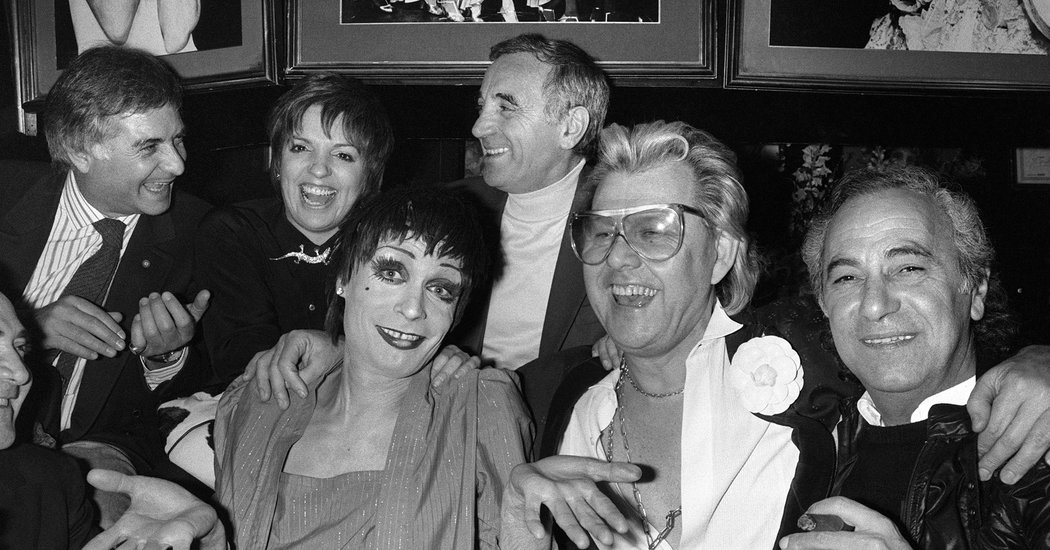

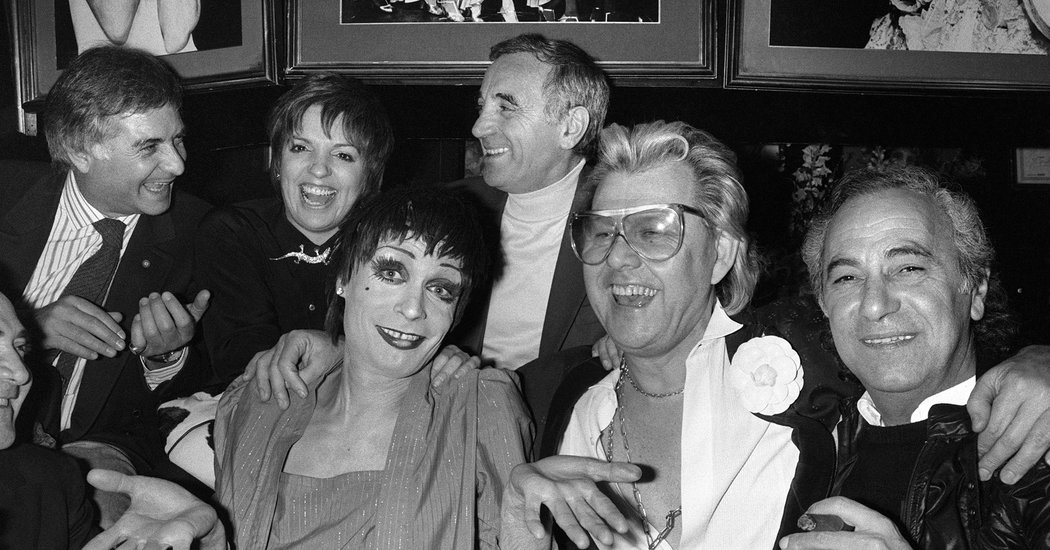

Prominent politicians, actors and singers were his friends, and his cabaret was lined with photos of him hugging the likes of Sophia Loren and Jacques Chirac, who as president of France had awarded him the Legion of Honor, the country’s highest order of merit. He was a close friend of first ladies of France, including Brigitte Macron, President Emmanuel Macron’s wife, who, like Michou, hailed from Amiens, an industrial town in northern France.

Chez Michou’s big draw was a colorful spectacle called “transformiste,” featuring a parade of performers in drag impersonating female luminaries of bygone eras, like the diva Maria Callas and Dalida, the Egyptian-born singer and actress from the 1950s. Night after night, the cabaret was packed with visitors from around France and from around the world.

As one of Paris’s most famous openly gay performers, Michou left another cultural mark: “He helped open doors to liberate others,” François Soustre, a French writer who is the co-author of an autobiography of Michou, told The Times last March.

Michel Georges Alfred Catty was born in June 1931 in Amiens and raised by his mother and a grandmother. At age 19, he wrote, he told his mother he was attracted to men.

“What would you say if I was a homosexual?” he recalled asking her.

She responded, “If you’re happy, that’s all I care about.”

Her support gave Michou confidence to leave Amiens and make his way to Paris, where he settled near the legendary Moulin Rouge cabaret. He found work at a cafe on Rue des Martyrs. After befriending the owner, he eventually bought the cafe from her, transforming it into a dinner theater featuring himself and two friends as dancers.

“I did the cooking, the cleaning and the dancing,” he said.

Michou famously avoided drinking water, preferring to hydrate himself with up to two bottles of Champagne a day — a habit that, by his account, once prompted a former first lady, Bernadette Chirac, a close friend, to admonish him.

He replied: “I don’t smoke, and I don’t do drugs. At least leave me the pleasure of Champagne!”

He is survived by his longtime companion, Erwann Toularastel; a half sister, Micheline; and a niece, Catherine Baudelin.

His last wish was that Chez Michou be shuttered on the day he died, said Mr. Deblaye, his publicist. As of Sunday night, the nightclub remained open, but how long it will continue to operate is uncertain.

Michou had made one thing clear, however. “When I disappear,” he told The Times, “I want people to remember this place and say, ‘This is where Michou gave people joy.’”

His coffin — a blue one, of course — was scheduled to be brought to the cabaret on Thursday for people to pay respects, according to his wishes, Mr. Deblaye said. He will be buried in the small St. Vincent cemetery in Montmartre, in a blue tomb.

Aurelien Breeden contributed reporting from Paris.