Late last month, during the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair at the Park Avenue Armory, Rebecca Romney withdrew a copy of “Howl, Kaddish, and Other Poems,” by Allen Ginsberg from her booth’s display case. She did so not to recite from its pages but to show off the writing in the margins.

Amy Winehouse had puzzled out lyrics to an unrecorded song alongside Ginsberg’s lines. “You see her artistic process,” Ms. Romney said. “And it’s right next to someone else’s art that she was consuming while creating something new.” The Ginsberg text is the centerpiece of Ms. Winehouse’s 220-book collection, which Ms. Romney’s company, Type Punch Matrix, near Washington, D.C., is in talks to sell as a unit for $135,000. “It shows a life lived through books,” she said.

Ms. Romney is an established seller known to “Pawn Stars” fans as the show’s rare books expert. But at 37, she represents a broad and growing cohort of young collectors who are coming to the trade from many walks of life; just across the aisle, Luke Pascal, a 30-year-old former restaurateur, was presiding over a case of letters by Abraham Lincoln and George Washington.

Michael F. Suarez, the director of the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia, said that these days, his students are skewing younger and less male than a decade ago, with nearly one-third attending on full scholarships.

“The world of the archive is actually considered pretty hip,” he said.

Of course, most entry-level collectors can’t plunk down hundreds of thousands of dollars for a first edition. But by frequenting estate sales and used bookstores, scouring eBay for hidden gems and learning how to spot value in all kinds of items, enthusiasts in their 20s and 30s have amassed collections that reflect their own tastes and interests.

Their work has been elevated by prizes from organizations and sellers such as Honey & Wax in Brooklyn, which recognize efforts to create “the most ingenious, or thoughtful, or original collections,” as opposed to the most valuable, Professor Suarez said. As a result, they are helping to shape the next generation of a hobby, and a rarefied trade.

Several young attendees stood out among the business-attire-and-book-core crowd at the fair — in particular Laura Jaeger, a petite 22-year-old with a shock of pink hair. Her mother, Jennifer Jaeger, owns Ankh Antiquarian Books in Chadstone, Australia, which specializes in books about Ancient Egypt; Laura is in the process of becoming a partner in the business.

She plans to expand its collection to reflect her interests, she said, like metaphysics and photography. “But I still know my Greek, Roman, Egyptian rare books really, really well,” she said. “I’ve been able to value books for a few years now.”

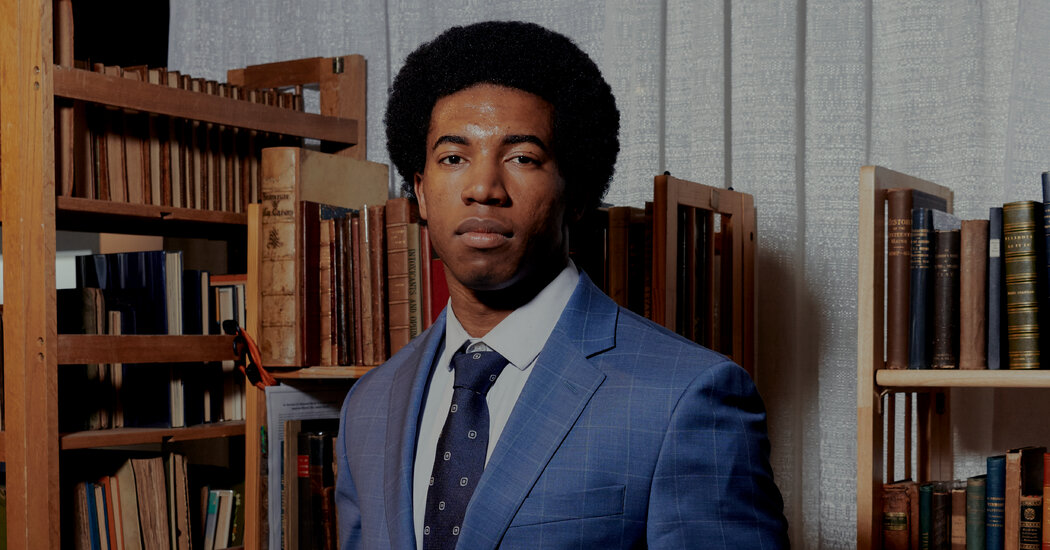

Kendall Spencer, 30, also hopes to leave his mark on the antiquarian book world. A Georgetown Law graduate who became enamored with rare books while researching Frederick Douglass, he is working as an apprentice at DeWolfe & Wood Rare Books while he prepares to take the Massachusetts bar exam.

“If you walk around here, there’s no one behind a booth that looks like me,” said Mr. Spencer, who is Black.

The Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America, a trade group with more than 450 members, hopes to see that change. The group started a diversity initiative in 2020 to “encourage and promote the participation of L.G.B.T.Q.+, BIPOC, and underrepresented groups in the world of book collecting and the trade,” Susan Benne, the organization’s executive director, wrote in an email. The group also introduced a paid internship program placing participants at member firms.

“I want to see more people like me take an interest,” Mr. Spencer said, “and I think that starts with someone inviting people in.”

First Editions Everywhere

When they’re starting out, most collectors focus on used and vintage books that matter for personal reasons, sourced from thrift stores, used bookstores and other amateur enthusiasts.

Thomas Gebremedhin, 34, a vice president and executive editor of Doubleday, started buying paperbacks from thrift stores in his early 20s while enrolled in the Iowa Writers Workshop, as a way to read out-of-print authors of color, such as Gayl Jones. These days, he can afford much pricier rare books, though he also picks up first-edition hardcovers for less than $10 at a “secret” bookstore in Brooklyn.

“You can find first editions anywhere,” said Mr. Gebremedhin, whose collection includes thousands of titles. “They should have a TLC show. You know that coupon show? I feel like there should be an equivalent for book shoppers.”

Camille Brown, 30, began collecting books when she was 23 and working at the Letterform Archive in San Francisco. “I started posting on Instagram about the things I was digitizing, which then led to posting about my own personal collection,” she said, which includes books on woodworking and joinery. (Her father is a contractor.) Soon, people started asking her for sourcing tips.

“It showed me there was more of an interest in the market than I realized,” Ms. Brown said. Now, she is an amateur book dealer on the platform and curates vintage books for clothing boutiques, sourcing most of her materials from library and estate sales.

Ms. Romney started collecting rare books at age 23, when she was hired by Bauman Rare Books in Las Vegas — a job she assumed her bachelor’s degree in classical studies and linguistics would not qualify her for. But she discovered that “general bookishness” was the only real prerequisite; anyone nerdy, curious and thrifty enough could get into it.

She said that collecting can be “an exercise in autobiography” — a way of seeing facets of their own experience refracted through the looking-glass of another’s life. For example: Margaret Landis, 30, is an astrophysicist who collects texts related to the cometary discoveries of Maria Mitchell, the first female astronomer in the United States. And Caitlin Gooch, the founder of a literacy nonprofit in North Carolina, collects nonfiction related to Black equestrians.

Ms. Gooch’s father and uncle had been documenting the family’s “cowboy history,” she said, before her uncle died and the collection was lost. “We don’t know where those pictures and videos are,” she said, “so for me, finding these books, even though they’re not directly about my history, means I’ll be able to share the information from them.”

Judging a Book by Its Dust Jacket

Beyond the link they offer to the past, collectors feel drawn to titles and editions that look good. It’s why, as Jess Kuronen put it, the dust jacket of a book plays a considerable role in pricing.

Ms. Kuronen, 29, is an owner of Left Bank Books in Manhattan, which caters to what she calls “entry-level” collectors. At her store, a first edition of “On the Road” without the dust jacket is priced at $500. A “near-fine” first edition with the jacket recently sold for nearly $7,000.

At Rare Book School, Professor Suarez said, students “learn how to read graphical codes, the illustrations, and the social codes” to understand “the life of that book over time in various communities.”

“There’s definitely people who strictly want to buy used books versus newer books,” said Addison Richley, 28, who owns Des Pair Books in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. Once she finishes a book she likes, she scours the internet for “a prettier copy or a more interesting edition.” Recently, a customer declined to buy a new copy of a vintage book they’d seen on the store’s Instagram.

“They explained to me that a used book is more special because it has character,” Ms. Richley said.

Brynn Whitfield, a 36-year-old tech publicist, started collecting antique chess books five years ago. “I’m getting more and more compliments about having these items in my house,” she said. “People think it’s cooler than typical coffee table books.”

Though used book sales thrive online, most sellers believe there’s a serendipity that only browsing in person can offer.

“In our time, so much is trying to sell you what the machine thinks that you want already,” said Josiah Wolfson, the 34-year-old proprietor of Aeon Bookstore, a subterranean shop in Lower Manhattan. “I don’t want to presuppose what everybody is looking for, even if they are collecting a specific thing.”

Sometimes the book that jumps isn’t one a collector would have planned to acquire at all. But, as Mr. Gebremedhin put it, the “emotional logic” of a vintage cover ends up speaking to the collector.

“I just got a first edition ‘Naked and the Dead,’” he said. He’s not a fan of Norman Mailer, its author. But: “It’s a beautiful cover.”

Making Space on the Shelf

The used and rare book market is a circular system of materials and ideas, and many young collectors, including Mr. Wolfson, see their shelves as “fluid.” He frequently culls his personal collection of spiritually inflected titles for Aeon stock, a process he compares to divination. If a book no longer matters to him, he said, “somebody else should really get the benefit.”

Mr. Gebremedhin is considering donating his collection to the Columbus Public Library in Ohio, where he grew up. He gave away 500 books before moving to a new apartment in Brooklyn. “A lot of the books that come into my house eventually find someone else,” he said. “It’s kind of the beauty of reading and sharing them.”

Ms. Brown, who sells books through Instagram, said that “accessibility” is a guiding impulse in her work. The internet, she said, “opens the door to these objects living many more lives that they wouldn’t have lived otherwise.”

Back at the fair, Jesse Paris Smith, 34, and her mother, the singer-songwriter Patti Smith, were looking at a book written by Charlotte Brontë when she was 13. For the two of them, poring over texts and covers has been a source of bonding. (Patti started collecting books around the age of 9, when she purchased “A Child’s Garden of Verses” at a church bazaar for 50 cents; today, it’s worth $5,000.)

“Jesse’s made books, and I’ve sold them,” Patti said. “I’ve done inventory, packed them, gift-wrapped them, charged them.”

The Smiths routinely give books away, too. “It’s painful, but we try to put the ones that we’re not reading back out into the world,” Jesse said.

“But not our special books!” Patti said.