A new study investigates calcium and heart disease.

“Heart disease is the leading cause of death for men and women,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Being able to identify people at risk is therefore a crucial public health issue.

One way to determine a person’s risk of heart disease, stroke, or heart attack is by looking at their coronary artery calcium (CAC) levels.

Calcium plays a number of roles in the body, including keeping bones healthy. However, calcium present in coronary arteries can lead to the accumulation of plaque.

Over time, this calcified substance can cause atherosclerosis, or a narrowing of the arteries. Atherosclerosis restricts blood flow and oxygen supply to vital organs, potentially resulting in a heart attack or stroke.

High cholesterol levels can indicate that a person is at risk; but scientists can also test CAC levels directly.

Using a CT scan to take numerous sectional pictures of the heart, doctors can see specks of CAC. A person’s scores tend to range from zero to over 400. The higher the score, the higher the risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

Cholesterol guidelines from 2018 recommend a CAC scan for people ages 40–75 whose risk status is “uncertain,” note the American Heart Association (AHA).

A new study, the results of which now appear in the journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging, has examined the CAC scores of younger people and drawn some interesting conclusions.

Heart abnormalities

The scientists used data from almost 2,500 people to track CAC and heart structure differences between young adulthood and middle age. Women made up 57% of the group, and 52% of participants were white.

They took data from participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, which began in the 1980s with the aim of identifying young adult risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

“We looked at early adulthood to middle age because this is a window in which we can see abnormalities that might not be causing symptoms, but could later increase the risk of heart problems,” explains study co-author Dr. Henrique Turin Moreira.

The researchers compared test results from years 15 and 25 of the CARDIA study period. At the 25-year mark, the average age of the group was around 50.

When it came to their CAC results, 77% of participants had a score of zero in year 15 of the study. However, in year 25, this had dropped to 72%.

A number of factors were linked to a rise in CAC scores, including being older, being male, being black, smoking, having higher cholesterol levels, and having higher systolic blood pressure.

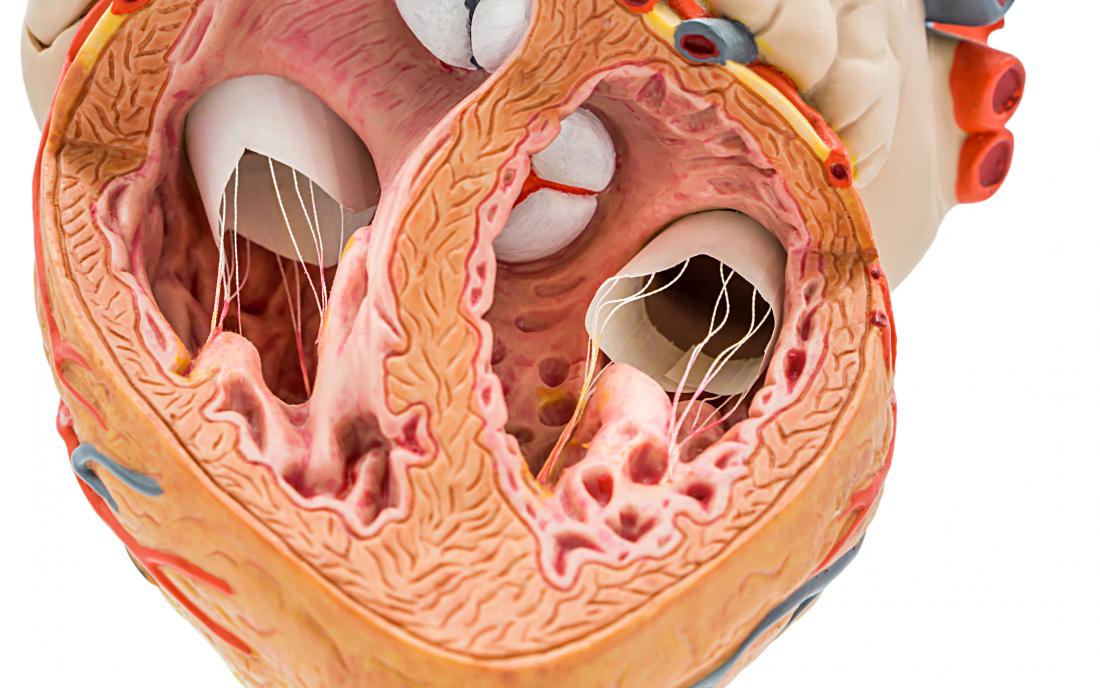

Middle-aged people who had higher CAC scores also showed a 9% increase in left ventricular volume and a 12% increase in left ventricular mass.

When the left ventricle changes in this way, the heart has to put more effort into pumping blood. This, in turn, leads to a thickening of the heart, which increases the risk of heart failure.

The study authors also note that these abnormalities were more significant among black people. For these people, every one-unit change in their CAC score correlated with quadruple the increase in their left ventricular mass.

Future implications

It is unclear why people exhibited such differences depending on their race. Dr. Moreira explains that it could be “due to genetic factors or perhaps greater exposure to cardiovascular risk factors that usually appear earlier” in black people.

What that do already know, however, is that black people are already more likely to develop cardiovascular disease. Although just 43% of white women and 50% of white men have cardiovascular disease, it affects 57% of black women and 60% of black men.

Further research, explains Dr. Moreira, will be needed to “examine the link between coronary artery calcium and heart health” — especially in relation to race. However, documenting the relationship between CAC and heart failure risk factors in a younger age group is significant.

“Given the burden of morbidity and mortality associated with heart failure, these are important findings,” says Dr. Salim Virani, a co-author of the AHA’s 2018 cholesterol guidelines.

“Prior studies from this cohort have also shown that a better risk factors profile in young adulthood is associated with much lower CAC and therefore, these results further highlight the importance of primordial prevention and risk factor modification in early adulthood.”