Matter

Scientists are focusing on a relatively small number of human genes and neglecting thousands of others. The reasons have more to do with professional survival than genetics.

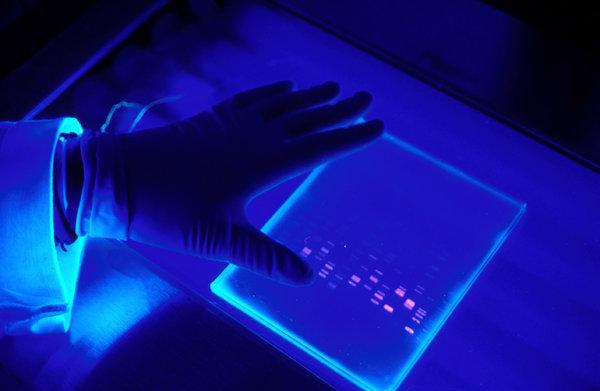

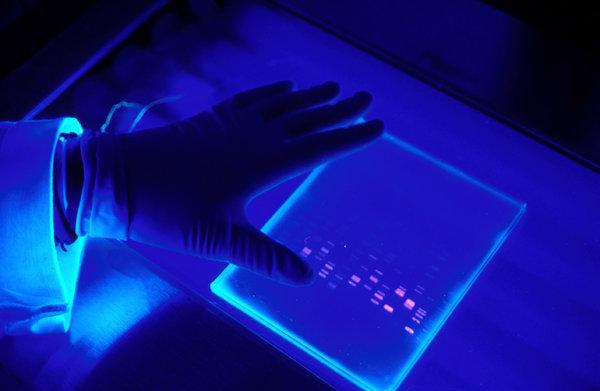

DNA being sequenced in a process called gel electrophoresis. An enormous chunk of the human genome remains unstudied despite significant technological advances.CreditCreditEurelios/Science Source

You have a gene called PNMA6F. All people do, but no one knows the purpose of that gene or the protein it makes. And as it turns out, PNMA6F has a lot of company in that regard.

In a study published Tuesday in PLOS Biology, researchers at Northwestern University reported that of our 20,000 protein-coding genes, about 5,400 have never been the subject of a single dedicated paper.

Most of our other genes have been almost as badly neglected, the subjects of minor investigation at best. A tiny fraction — 2,000 of them — have hogged most of the attention, the focus of 90 percent of the scientific studies published in recent years.

A number of factors are largely responsible for this wild imbalance, and they say a lot about how scientists approach science.

Researchers tend to focus on genes that have been studied for decades, for example. To take on an enigma like PNMA6F can put a scientist’s career at risk.

“This is very worrisome,” said Luís A. Nunes Amaral, a data scientist at Northwestern University and a co-author of the new study. “If the field keeps exploring the unknown this slowly, it will take us forever to understand these other genes.”

A gene may come to light because scientists encounter the protein it encodes. At other times, the first clue comes when scientists recognize that a stretch of DNA has some distinctive sequences that are shared by all genes.

But giving a gene a name doesn’t mean you know what it does.

Consider a gene called C1orf106. Scientists found it in 2002 but had no idea of its function. In 2011, researchers found that variants of this gene put people at risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Yet they still had no idea why.

In March, a team of researchers based at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Mass., solved the mystery. They bred mice that couldn’t make proteins from C1orf106, and found that the animals developed leaky guts.

That protein, the scientists discovered, keeps intestinal cells properly glued together. Now investigators have a new way to look for treatments for inflammatory bowel disease.

Researchers noticed that something was wrong with the study of human genes as early as 2003. Just a small group of them attracted most of the scientific attention.

Genetics has changed dramatically since then. Scientists now have a detailed map of the human genome, showing the location of just about every gene on the human genome, and the technology for sequencing DNA has become staggeringly powerful.

Recently, Dr. Amaral and his colleagues checked to see if researchers had broadened their focus by analyzing millions of scientific papers published up to 2015. Our knowledge about human genes, the team found, remained wildly lopsided.

Not only did Dr. Amaral and his colleagues document the ongoing imbalance, they tested 430 possible explanations for why it exists, ranging from the size of the protein encoded by a gene to the date of its discovery.

It was possible, for example, that scientists were rationally focusing attention only on the genes that matter most. Perhaps they only studied the genes involved in cancer and other diseases.

That was not the case, it turned out. “There are lots of genes that are important for cancer, but only a small subset of them are being studied,” said Dr. Amaral.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Just 15 explanations mostly accounted for how many papers have been published on a particular gene. The reasons have more to do with the working lives of scientists than the genes themselves.

For example, it’s easier to gather proteins that are secreted than ones that stay trapped inside cells. Dr. Amaral and his colleagues found that if a gene creates a secreted protein, that gene is much more likely to be well studied.

It’s also easier to study a human gene by looking at a related version in a mouse or some other lab animal. Scientists have succeeded in creating animal models for some genes but not others.

Genes that are studied in animal models tend to be studied a lot in humans, too, Dr. Amaral and his colleagues found.

A long history helps, too. The genes that are intensively studied now tend to be the ones that were discovered long ago.

Some 16 percent of all human genes were identified by 1991. Those genes were the subjects of about half of all genetic research published in 2015.

One reason is that the longer scientists study a gene, the easier it gets, noted Thomas Stoeger, a post-doctoral researcher at Northwestern and a co-author of the new report.

“People who study these genes have a head start over scientists who have to make tools to study other genes,” he said.

That head start may make all the difference in the scramble to publish research and land a job. Graduate students who investigated the least studied genes were much less likely to become a principal investigators later in their careers, the new study found.

“All the rewards are set up for you to study what has been well-studied,” Dr. Amaral said.

“With the Human Genome Project, we thought everything was going to change,” he added. “And what our analysis shows is pretty much nothing changed.”

If these trends continue as they have for decades, the human genome will remain a terra incognito for a long time. At this rate, it would take a century or longer for scientists to publish at least one paper on every one of our 20,000 genes.

That slow pace of discovery may well stymie advances in medicine, Dr. Amaral said. “We keep looking at the same genes as targets for our drugs. We are ignoring the vast majority of the genome,” he said.

Scientists won’t change their ways without a major shift in how science gets done, he added. “I can’t believe the system can move in that direction by itself,” he said.

Dr. Stoeger argued that the scientific community should recognize that a researcher who studies the least known genes may need extra time to get results.

“People who do something new need some protection,” he said.

Dr. Amaral proposed dedicating some research grants to the truly unknown, rather than safe bets.

“Some of the things we would be funding are going to fail,” he said. “But when they succeed, they’re going to open lots of opportunities.”

Advertisement