In a Black History Month roiled by tone-deaf scandals in politics and fashion involving blackface, shoes and balaclavas, you may have missed the one about mammy jars.

Grace Coddington, a former creative director of American Vogue, was photographed with a collection of so-called mammy ceramics in her kitchen for a French lifestyle magazine. The images surfaced in early February and were condemned.

“I am ashamed and embarrassed that I didn’t see the mammy jars in the photo until an Instagram commenter pointed them out to me,” the photographer, Brian Ferry, said in a statement. “I’m sorry for my mistake and the hurt it caused,” he added. “I am committed to doing better in the future.” Representatives for Ms. Coddington did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The mammy stereotype portrays black women as obedient maids to white families. Like blackface, racist objects such as mammy jars perpetuate deep-rooted stereotypes about African-Americans by portraying them as docile, dumb and animated. But some white families view these objects as keepsakes, passed down through generations as relics of the past.

More than a century after the heyday of minstrel shows and the peak production of racist objects, some Americans are still learning about the how these cultural products — viewed as forms of entertainment and decorations during the Jim Crow era — dehumanize black people.

This year, February — a month usually set aside for celebrating the achievements of African-Americans — was dominated by a national reckoning with blackface and a series of apologies for racist behavior.

Ralph S. Northam, the governor of Virginia, first apologized for appearing in a photo on his yearbook page that shows a man in blackface standing next to a man in a Ku Klux Klan robe, and then he denied appearing in the photo at all. The governor later admitted to putting shoe polish on his face to dress up as Michael Jackson. Days later, Virginia’s attorney general apologized for wearing blackface at a college party. (Both men are still in office.)

Conversations about racist controversies, in politics or fashion, are often framed in terms of how they are offensive to black people, but that leaves out a crucial issue, according to Chico Colvard, the director of a new documentary about the history of racist objects.

“The other part of the equation is that these are persistent markers of white supremacy,” Mr. Colvard said.

Racist objects were originally used as propaganda tools to spread falsehoods about the Civil War.

Their production spiked in the 1890s, said Rhae Lynn Barnes, an assistant professor of American cultural history at Princeton University.

“A lot of this iconography is specifically around the kitchen and making jokes about cooking and cleaning,” Dr. Barnes said. While blackface, a signature of minstrel shows, was often performed in public by white men to mock African-Americans, black figurines were found in homes, according to Dr. Barnes.

Mammy miniatures — jars, salt and pepper shakers, kitchen bells — show a black woman with exaggerated lips in a red-and-white gown and a matching head scarf. Lawn jockeys depict hunched-over black men holding lanterns. Mechanical banks feature bugged-out eyes that roll back into a man’s head when coins are inserted into his smiling mouth.

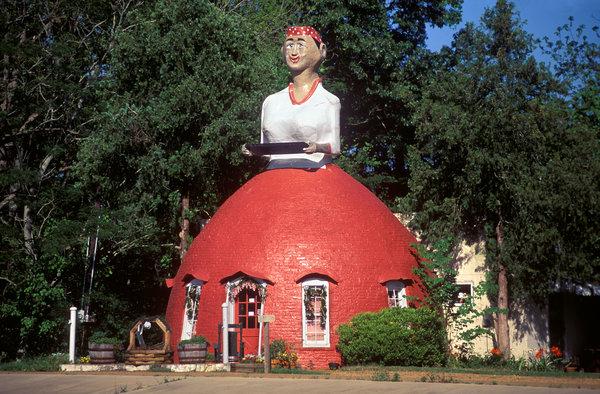

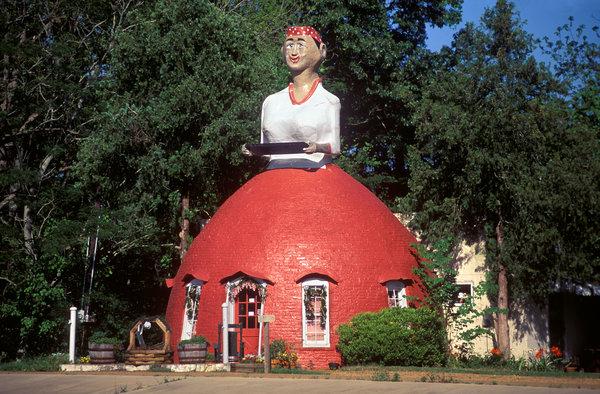

Mammy’s Cupboard, a restaurant and roadside attraction, in Natchez, Miss. The woman’s skin was painted a lighter shade during the civil rights era to address criticism.CreditClassicStock/Alamy

“They were everyday objects which portrayed black people as ugly, different and fun to laugh at,” said David Pilgrim, the founder of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Michigan. “They were, in a word, propaganda.”

The objects still show up in our society today.

When Barack Obama first ran for president, “jolly Obama banks” appeared online as gag gifts.

And in an episode of the Netflix comedy “Master of None,” the main character, Dev Shah, played by Aziz Ansari, ends a series of bad Tinder dates with a promising hookup. His partner asks him to grab a condom from her bedside table, and he finds one stashed in a mammy cookie jar.

“Isn’t it a little racist?” Dev asks the woman, who is white.

She gets defensive and asks Dev why he waited until after having sex with her to comment on the object. “Just show it to a black person sometime,” he replies.

Some people collect the objects as investment pieces: At antique shows a few decades ago, the banks were priced from $400 to $600, and mammy jars were sold for $200 to $400, according to Dr. Pilgrim. But sites like eBay led to lower price points.

“What an interesting culture we have, where you have price guides not just for mammy ceramics and salt and pepper shakers, but also for lynching postcards,” Dr. Pilgrim said.

“Black Memorabilia,” Mr. Colvard’s documentary, which aired on PBS in February, follows a worker who makes mechanical banks at a small factory in China, a woman who sells antiques at a flea market in North Carolina and an artist who grapples with racism through performance art.

Mr. Colvard, who is black, was born in Germany and raised in the United States. He grew up “unconsciously consuming a steady diet” of racist images, he said, from Aunt Jemima on boxes of pancake mix to Saturday morning specials with Shirley Temple in blackface.

“A child is not going to gravitate toward a toy that’s hideous or not well designed,” Mr. Colvard said. “Of course it’s appealing — the colors are bright, welcoming and animated.”

His documentary often weaves in clips from Black Lives Matter protests and the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., to draw connections between the pain African-Americans feel when seeing household caricatures of themselves and the political trauma they experience today.

One scene from the documentary shows Joy, the antiques dealer, at a market outpost in Massachusetts. The camera cuts to a black boy drinking water out of a spigot. “I want the little one, you’re too cute,” says Joy, who is white.

An innocuous comment on its own, her words take on a darker tone in view of the types of items she sells and collects: mechanical banks, minstrel postcards, slave documents, K.K.K. pamphlets. “She sees herself as a preserver of history, of real black history,” Mr. Colvard said in an interview. “She sees this as a history of travail.”

The antiques dealer says she collects the artifacts to “take the wall down between the races.” But profiting from objects that exploit black suffering may suggest a skewed understanding of African-American history and identity. “These are objects used to dehumanize us,” Mr. Colvard said.

Dr. Pilgrim, who is black and has been a collector since he was a child, said some people collect the figurines to keep them off the market.

“I knew people who bought them because they wanted to remind themselves of how far black people had come and how resilient black people had been,” he said.

But others collect them as investment pieces and as a form of nostalgia.

“Where a person like myself is likely to see the vestiges of slavery and segregation,” he said, “someone else might be reminded of good times spent with their parents or grandparents and not see the connection at all.”

Nostalgia for these objects nods to the post-Reconstruction era, a time when the United Daughters of the Confederacy mapped out the blueprint for the Lost Cause, a cultural campaign that denied slavery was the reason for the Civil War.

“These figurines laud that time and present a ‘moonlight and magnolias’ view of slavery,” said Keri Leigh Merritt, an Atlanta-based historian and the author of “Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South.” “They show happy slaves and try to minimize the brutality and the violence and the horror that we know actually happened.”

Dr. Pilgrim, whose museum houses over 5,000 collectibles, hopes the mass presentation of the memorabilia encourages people from various groups to interrogate the messages behind the figurines.

“There’s a reason we need to have these things: To serve as reminders so we’ll never forget,” Mr. Colvard said.

“They shouldn’t be erased from history,” he added, “but I’m not sure they should be casually bought and sold in a regular stream of commerce either.”