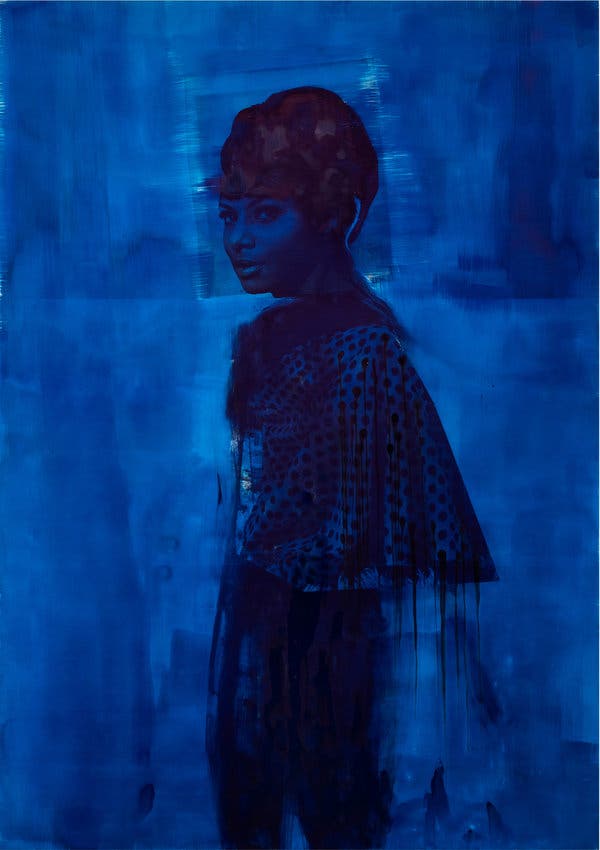

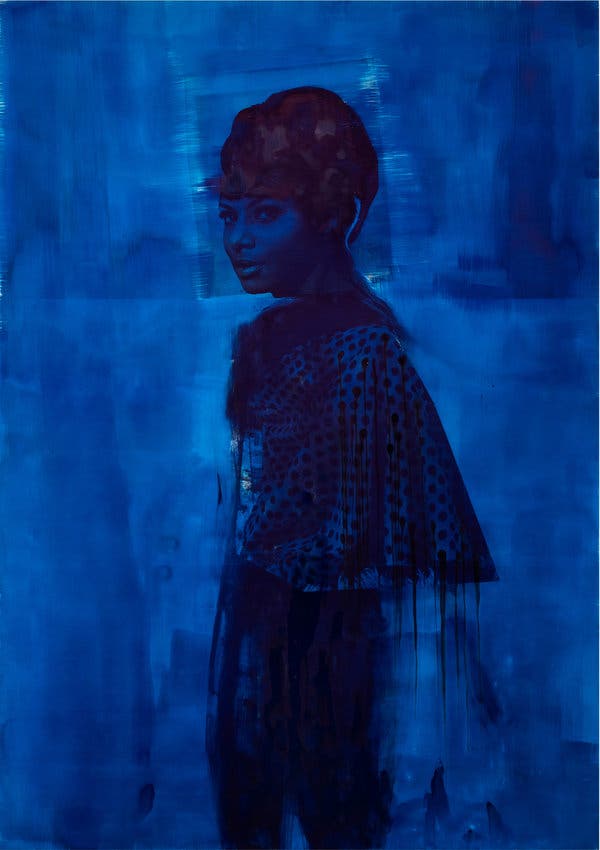

The mood is blue in the new paintings of Lorna Simpson. Blue like glaciers in polar night. Blue like a frigid ocean. Blue like premonition, blue like the blues.

“Dark times, to me, mean dark paintings,” the artist said recently, in her spacious new studio at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Big, brooding landscapes, up to nine feet tall, lined the wall. Dark blue tones — cobalt, navy, midnight — nearly saturated them, with areas of respite in turquoise and a bleary, overcast gray. Other paintings, slightly smaller, of superimposed faces of black women against abstract backgrounds were intimate, but just as engulfing.

At 58, Ms. Simpson is taking measure of the moment — political, personal — in her distinctive way: indirectly, with open-ended meanings and an element of mystery.

Her paintings, currently on view at Hauser & Wirth, in Chelsea, mark a formal change. She has long been known as a photographer, whose black-and-white portraits of subjects looking away or cut off by the frame, with fragmentary captions that read as if lifted out of an unfolding story, announced her in the 1980s as a major voice in black feminist art. Her work expanded into a rich range of photo, video, and installation that was seen in a midcareer survey at the Whitney Museum in 2007.

She had not painted, however, since her early days of art school at the School of Visual Arts, four decades ago. She began to experiment with it just five years ago, with a set of works that her friend, the curator Okwui Enwezor, included in the 2015 Venice Biennale.

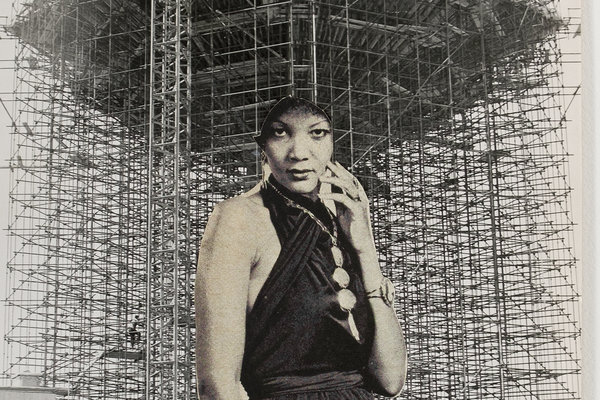

Lorna Simpson’s “Source Notes,” 2019, ink and screenprint on gessoed fiberglass.CreditLorna Simpson and Hauser & Wirth

“I did them in this really red-hot way and then went on to other things, and wanted to return to that language and see how I might handle it now,” she said.

As seen in the show at Hauser & Wirth, titled “Darkening,” Ms. Simpson’s paintings in fact contain a cascade of connections to her earlier art-making that manifest once the elements of method appear, making this new phase more an evolution than a break.

“She’s taken everything she’s made and moved into new territory,” said Thelma Golden, the director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem and a close observer of her work.

Ms. Simpson begins with vintage photographs: century-old black-and-whites of polar expeditions for the landscapes; pictures in ads and articles in Ebony magazine, one of her go-to sources, from the 1950s through 1970s for the portraits.

These are digitally enlarged, screenprinted, and transferred onto her painting surfaces, mostly fiberglass board. She also introduces vertical strips of text, sliced from Ebony pages then magnified, that flash across the composition, too narrow to decipher.

Only then does she paint, using ink — an ingredient, she pointed out, imported from her recent work in drawing and collage, now deployed at massive scale.

“I love trying to figure out how to have that same quality,” she said. “The liquidity of the ink, but also its iridescence, the way that it pools, the way that I can make areas opaque.”

This work of obscuring disrupts the landscapes, some of which are already composites of several source images. The tones and densities of ink merge land and water, cover horizon lines, streak and tumble across the frame. The effect is a reverting, toward something illegible, inchoate.

In the studio, Ms. Simpson called the glacial pieces “abstractions of landscapes.” She paused. “Maybe, in a particular way, they’re suggestions.”

The dark times, for Ms. Simpson, have been both private and collective. In the past year, she said, several people to whom she was close have passed away — most recently Mr. Enwezor, the celebrated and influential curator, who died in March at 55.

“There’s been a lot of death,” she said. “You go to the studio, and you’re like, ‘I don’t feel like doing anything today but crying.’ That kind of sadness. But I’ve learned that it’s so much better to push yourself and do work, and embrace that state.”

The other part of it is the political situation.

“It feels very much like living in the moment of fascism in the United States, that spreads and gives permission all over the world,” she said. “That permission it’s giving is very scary. In our safety, on an individual level, I feel it.”

The draw toward images of harsh Arctic settings stems in part from these emotions. Allusions to climate change, though she does not reject them, are not the main aim. But her choice of source images from early polar expeditions points elsewhere.

“I haven’t figured out everything yet,” she said. “But it does feel like a preoccupation with an environment that is historically inhospitable, with very dire rules for survival.”

Daily life in America, she said, was becoming a “heightened inhospitable condition.”

With Ms. Simpson, however, there is always another layer. The exhibition opens with a few lines by the poet Robin Coste Lewis, from “Using Black to Paint Light: Walking Through a Matisse Exhibit, Thinking About the Arctic and Matthew Henson.”

The poem refers to Henson, the African-American explorer who made multiple expeditions alongside Robert Peary near the turn of the 20th century, learning from the Inuit how to dwell in the terrain, but was neglected in most histories until long after his death in 1955.

The excerpt that Ms. Simpson chose from the poem evokes the landscape: Endless blueness. White is blue. And then: It makes me wonder — yet again — was there ever such a thing as whiteness? I am beginning to grow suspicious. An open window.

The poetry recalls Ms. Simpson’s own texts in early photographs such as “The Water Bearer” (1986), possibly her most famous piece, and her mid-1990s series “Public Sex,” of photographs printed on felt. In that series, she showed cityscapes devoid of human figures, the setting as vessel for the emotions in play.

“They were about this sense of self in a public space, and the psychological machinations of how one operates in a particular space and time of day,” Ms. Simpson said. Likewise, she viewed her new polar landscapes as “parallel to a psychological state.”

“Even her early work was about a sort of interior landscape,” Ms. Golden said. “They were intellectual landscapes informed by how we thought about personhood and self.”

Younger than Carrie Mae Weems and older than Kara Walker, Ms. Simpson is a major figure in the generation that forced institutional attention, and ultimately recognition, of black artists — particularly black women artists — at the vanguard of the culture at large.

Born in Brooklyn, she grew up in Queens, with a Jamaican-Cuban father and African-American mother. While in art school at S.V.A., she hung around the downtown club and performance scene. She interned at the Studio Museum, seeing up close the practice of David Hammons, among others, who was an artist in residence.

Her conceptual photography crystallized in the early 1980s, in graduate school at the University of California, San Diego, where she overlapped with Ms. Weems. When she returned to New York, she joined the budding black bohemia in Fort Greene.

Women artists such as Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman had led major advances in photo-based work, but the Pictures Generation scene, as Ms. Simpson remembers it, evinced little interest in black artists.

“I think sometimes there’s a lack of honesty about how segregated it was,” she said.

The Brooklyn milieu was young and interdisciplinary. Ms. Simpson was part of the theater collective Rodeo Caldonia, a feisty crew of women visual artists, performers and playwrights. The broader crowd included the Black Rock Coalition and the just-emerging Spike Lee.

“We were of a mind that you were never going to get permission to create the world you wanted to live in,” she said. “But people of like mind were just going to go for it.”

Her work, in that spirit, proceeded from a feminist point of view that was natural and taken as a given, with no need for polemics. Today, it is part of the evolving contemporary canon. Several of her early pieces capped, for instance, the landmark 2017 exhibition “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85” at the Brooklyn Museum.

“Lorna’s role is as a great innovator of the generation,” said Kellie Jones, the art historian and Columbia University professor who is her friend and contemporary. “People in many ways continue to see her as a photographer, but that’s going to become harder, because the innovation with materials is going to take over these designations.”

Ms. Simpson hinted that her mostly-blue period, in turn, might lift soon — if not from improvements in the world at large, then at least out of the intellectual restlessness she has made, throughout her career, into an artistic imperative.

“It’s more about the ideas,” she said.

Lorna Simpson: Darkening

Through July 26 at Hauser & Wirth, 548 West 22nd Street, Manhattan; 212-790-3900, hauserwirth.com.