After the births of my babies in the ’70s, the umbilical cord connecting them to me was cut and trashed. But these days the blood inside can be preserved in a bank. It contains stem cells with the potential to save the lives of patients with leukemia, lymphoma or sickle cell disease.

Stem cell treatments have been in the news lately because some companies are accused of selling unproven treatments that may actually harm patients. Earlier this month, the New York attorney general filed suit against one such company, claiming it knowingly performed rogue procedures on patients with a wide range of medical conditions. But there are legitimate lifesaving uses of cord blood that should not be tainted by these sham companies.

Liars and thieves must not be allowed to detract from meticulous scientific research that has made umbilical cord blood mystic in its regenerative powers.

A reader who is pregnant and whose first child had undergone successful leukemia treatments asked me about cord blood banking recently. Her obstetrician had suggested she bank her new baby’s cord blood as an insurance policy in case her first child suffered a recurrence. Cord blood transplants can be used to reconstitute a patient’s immune system. Blood from a sibling stands a good chance of being a suitable match for a transplant.

Two impediments may influence parents against the risk-free practice of banking cord blood. First, some obstetricians believe that a brief wait before the clamping of an umbilical cord can enhance a child’s well-being, but delayed clamping compromises the volume and quality of collected cord blood cells.

The second potential inhibition, the cost of banking, depends on whether the bank is public or private. The act of donating cord blood to a public bank, not for the use of the baby or family that contributed the cells, is free and provides a genuine service to other Americans. Private banking — for the baby or the baby’s family — has an upfront cost as well as yearly maintenance charges; however, expectant parents who have children with a cancer history can often find financial assistance.

Banked cord blood cells have been used in over 40,000 transplants worldwide to treat genetic disorders, malignant and not. I was surprised to discover that the researcher who played a pivotal role in originating cord blood transplants works at the cancer center that keeps me alive.

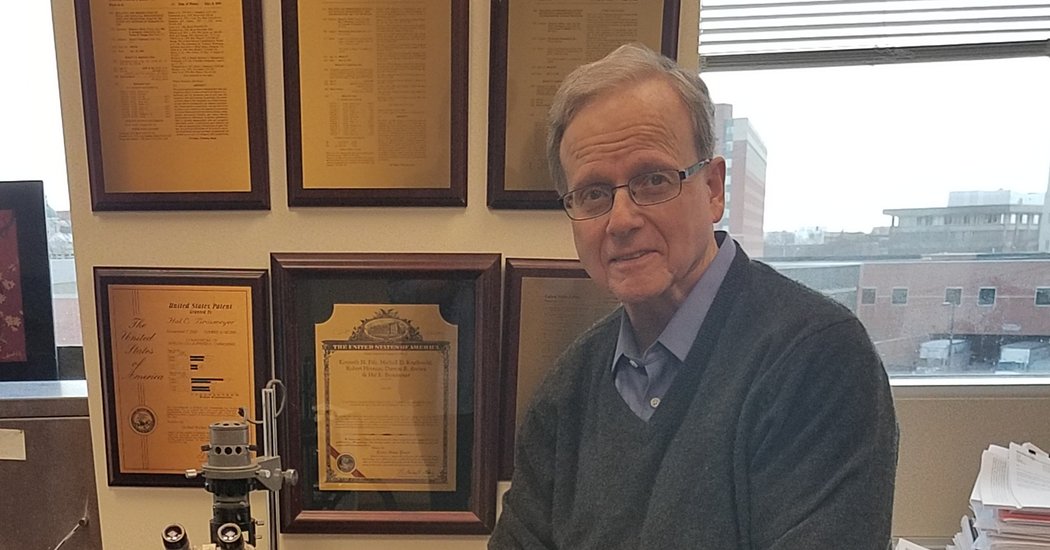

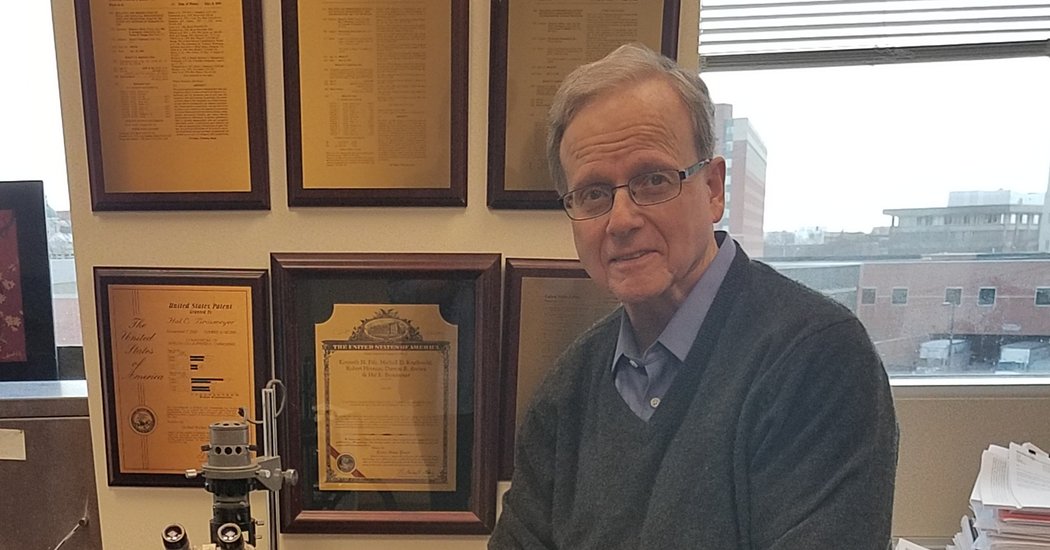

He is Dr. Hal Broxmeyer, a distinguished professor at the Indiana University School of Medicine. I asked him about the benefits of cord blood transplants, as well as when he and his collaborators discovered the idea and where research was headed.

Are cord blood transplants superior to other types of transplants? All have pros and cons, Dr. Broxmeyer explained. Cord blood is easier to collect than bone marrow, generates less life-threatening graft-versus-host disease, and can be used with “less stringent HLA-matching.” However, mobilized peripheral blood (collected from the bloodstream) engrafts faster than bone marrow, which engrafts faster than cord blood. Many investigators now study ways “to accelerate the engraftment of cord blood cells,” as he does.

Which parents should consider banking? Dr. Broxmeyer believes that families have to come to this decision with the help of informed physicians. “I personally would have stored my two sons’ cord blood, had they not been born before we started the field,” he said. “We did have my granddaughter’s cord blood stored.”

How did Dr. Broxmeyer, a biologist, help start the field? His lab, serving as the first proof-of-principle cord blood bank for distant obstetric units, began studying the capacity of hematopoietic (blood) stem and progenitor cells to cure disease in the early ’80s. Dr. Broxmeyer’s team generated enough data to convince the medical community that a cord blood transplant might work. Dr. Eliane Gluckman, at the Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, agreed to do the procedures with cells from Dr. Broxmeyer’s lab and to follow his suggestions in doing so.

In October 1988, Dr. Broxmeyer’s lab sent five ounces of blood overseas for a transplant needed by 5-year-old Matthew Farrow, who had Fanconi anemia: his bone marrow could not create enough healthy blood cells. The five ounces came from the umbilical cord of Matthew’s baby sister. Three weeks after the transplant, Matthew’s blood counts returned to normal and, Dr. Broxmeyer adds with understandable pride, “he is still alive and well.” It was the first cord blood transplant.

Preserved cord blood units were next hand-delivered to hospitals in Baltimore, Cincinnati, Minneapolis — for sibling cord blood transplants. The first cord blood transplant for a young child with leukemia occurred because a grandmother read a one-page article in a magazine that mentioned Dr. Broxmeyer’s work; she persuaded the doctors at Johns Hopkins to use cord blood from his lab. By the early 1990s, he was convinced that “cord blood transplants had a real place in treatment and health care.”

In his discussions of ongoing laboratory and clinical efforts to improve cord blood procedures, Dr. Broxmeyer argues that cord blood is particularly important for patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds who can encounter difficulties finding a compatible donor. Research is underway to determine if cord blood may help deal with birth asphyxia, cerebral palsy, stroke and autism, but he is “waiting for definitive clinical proof for these other uses.”

Work like Dr. Broxmeyer’s advances progress in health care that benefits us all. He himself is a cancer patient. My first oncologist, Dr. Daniela Matei, heard him speaking through a tracheotomy, after surgery for thyroid cancer. He had wanted to share one of his discoveries with his colleagues before it was published, she explained, and then she added, “his genuine love of science was so moving.” A cancer recurrence has only deepened his commitment to better understanding normal and malignant cell processes. “If anything,” he tells me, “I have been more focused and worked harder since the diagnosis.”

Stirred by his achievement, I take a loony pride in the coincidence that Dr. Broxmeyer attended Brooklyn College in the same years I attended City College. Public institutions of higher education: Where would we be without them? Or without all those assiduous grandmas who forward health care articles to mailboxes around the globe?

Susan Gubar, who has been dealing with ovarian cancer since 2008, is distinguished emerita professor of English at Indiana University. Her latest book is “Late-Life Love.”