Last year, right before the winter holidays, the nurse practitioner palpating my breast paused and returned to a certain spot.

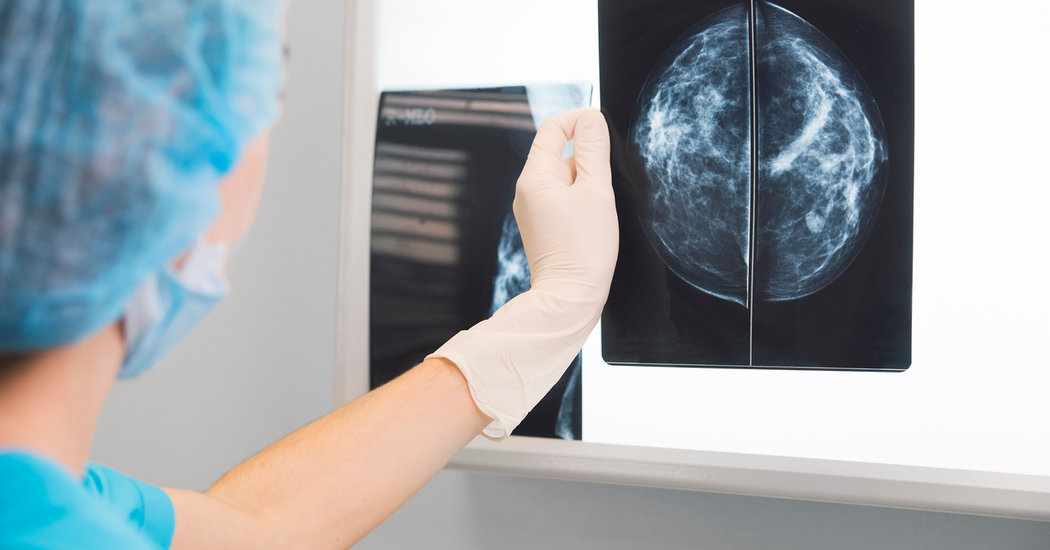

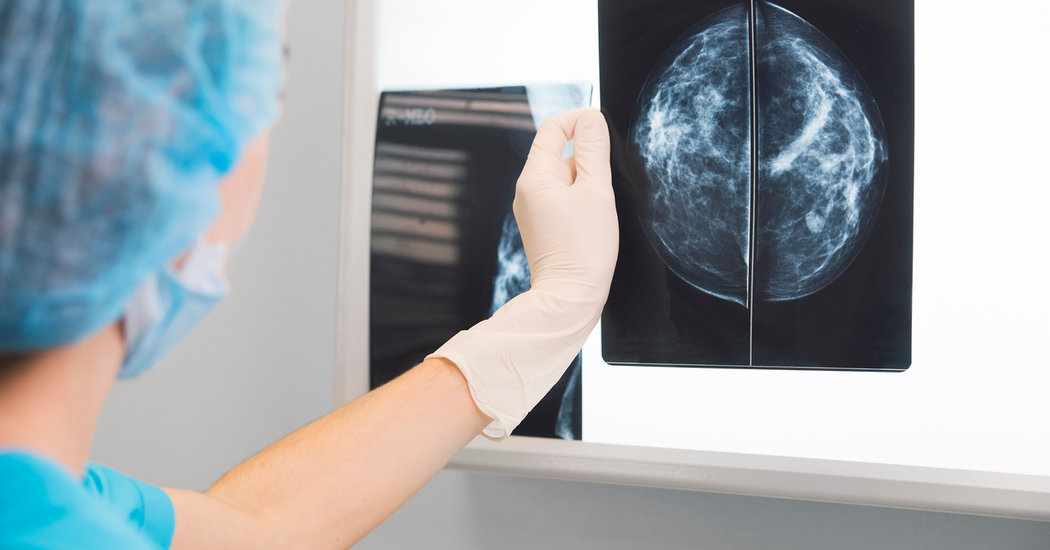

It was just below the port embedded in my chest that has been used for years of ovarian cancer treatment and above the scar from a previous lumpectomy. The terror that must overwhelm countless women engulfed me. “Maybe nothing,” she said, guiding my fingers to feel what she felt. “I’ll set up a mammogram.” I grimaced, knowing that anxiety always swamps me before scans.

No matter how long I deal with ovarian cancer, scanxiety threatens to assert its nasty vigor in advance of periodic blood tests and abdominal CTs. During my last breast cancer scare less than a year earlier, I had scanxiety over a mammogram and then a biopsy, which led to that lumpectomy. There would be seven fretful days between the detection of this second lump in the same breast and the scheduled scan. If the finding turned out to be indeterminate, should I “wait and see” since the last breast biopsy was painful? If the new growth was a recurrence, should I get a prophylactic double mastectomy?

Yet I knew from experience that this sort of frightful perseverating about potential — but not inevitable — decision-making squanders spirit and time. Without solid evidence, stressing over unknowns does not alter what the outcome will be; it only escalates angst. Yet scanxiety — by prompting us to stew about the future — eclipses the present. Even when no pending test looms on the horizon, the misuse of time and spirit depresses those of us who suffer from the condition patients call cancerchondria.

Like hypochondriacs, cancerchondriacs imagine every cough, twinge, bump or rash as a malignancy stealthily creeping back. Since cancer can recur with or without producing obvious symptoms, we may fritter away a remission of months in obsessive brooding. The dread of relapse hisses, snorts, whimpers, roars, drowning out all else. Checking our bodies for indications of disease, searching the internet for the causes of possible warning signs, we lay waste our powers. Healthy people can also suffer from cancerchondria, sometimes because a specific type of the disease is said to “run” in their family.

During my week of waiting, I had no choice but to cultivate a skill that seasoned cancer patients practice assiduously: The fine art of trying not to fret or fuss. Here are the techniques I used, though I am always on the lookout for more.

Counter-Irritants

It helps to fixate on urgent problems about which something should and can be done. In a lucky break, a book manuscript of mine had just been copy-edited. There were zillions of nitpicky queries about style and grammar that had to be answered immediately. Work of any kind inevitably offers exasperating diversions.

Worse Cases

Despite the self-absorption that unfortunately accompanies cancer scares, most older patients realize that there are others worse off than we are. While worrying about my own health, I saw a video about a mother grieving over a little boy dying of cancer. It reminded me that I had been given the gift of three-score-and-ten and should be relieved that my daughters were not facing my situation. Assisting someone worse off even more effectively derails compulsive introspection. Perusing the daily news can jolt us into an appreciation of the ghastly vulnerability of defenseless people and maybe motivate us to do something for those in our midst.

Escape Routes

The second season of “The Crown” appeared so I could engage in binge watching. When I’m anxious, the focus needed for my favorite pastime, reading, eludes me, but more physical enterprises like cleaning a closet or a car sometimes work. A friend embarks on what she calls retail therapy.

Repetitive Activity

Walking, woodworking, weeding, video games, sporting events or playing an instrument succeed for some. What helped me was yoga and writing in my diary, where I could concentrate on crafting the best sentences to convey my emotions rather than the emotions themselves.

Speech or Silence

Some people want to vent about their qualms, but others need to button up. For the most part, I’m mum.

Self-Medicating

If administered responsibly, martinis, beer, wine, tranquilizers or a few CBD-infused gumdrops can provide succor, as can a soothing bath, a massage, a quiet session of meditation or prayer.

The day before the scan, not thinking about it became impossible. I did not want my aging husband schlepping from our home in Bloomington, Ind., to the Indianapolis hospital to which we would have to traipse if I needed surgery. I didn’t want to be lopsided or to wear what a friend calls a “foob” (a fake boob). But could my weakened body withstand a double mastectomy? By the time I arrived at the imaging center, I was a wreck.

Last December, the mammogram technician informed me that there would also be a sonogram, after which a doctor would explain the results. It took about two hours, at the end of which the radiologist cut to the chase: “You’re fine,” he said. “Just scar tissue.” I broke into tears as I thanked him for a gift at the start of Hanukkah. I was about to rush out into the waiting room to tell my husband the good news, when the technician gently guided me to the locker where I had left my clothing.

One and a half days between the scheduling and the scan had been wasted, but not all seven: a mini-miracle! And then there was the high that, alas, only some cancer patients experience: the reprieve of not having to undergo yet another medical intervention.

There should be a word for that rush of euphoria when there is no evidence of further disease.

If you readers have suggested coinages, please leave them in the comments. After all, even a rose by another name needs a moniker. The next time I face cancerchondria or scanxiety, I hope to use your inventions, for the words patients create illuminate our worlds.

Susan Gubar, who has been dealing with ovarian cancer since 2008, is distinguished emerita professor of English at Indiana University. Her latest book, “Late-Life Love,” came out Tuesday.