A custom-made drone delivered a kidney this month to a Maryland woman who had waited eight years for a lifesaving transplant.

While it was only a short test flight — less than three miles in total — the team that created the drone at the University of Maryland says it was a worldwide first and a crucial step in its quest to speed up the delicate and time-sensitive task of delivering donated organs.

The team’s leader, Dr. Joseph R. Scalea, an assistant professor of surgery at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said he pursued the project after constant frustration over organs taking too long to reach his patients. After organs are removed from a donor, they become less healthy with each passing second. He recalled one case when a kidney from Alabama took 29 hours to reach his hospital.

“Had I put that in at nine hours, the patient would probably have another several years of life,” Dr. Scalea said Tuesday. “Why can’t we get that right?”

To carry out the project, Dr. Scalea’s team of medical experts worked with colleagues in aviation and engineering at the university, as well as the Living Legacy Foundation of Maryland, which oversees organ donations. He performed the transplant along with two other surgeons at the University of Maryland Medical Center, Dr. Rolf N. Barth and Dr. Talal Al-Qaoud.

The woman who received the kidney, Trina Glispy, a 44-year-old nursing assistant from Baltimore, said she had begun to lose hope before she got a call on April 18, when she learned she had matched with a donor.

Ms. Glispy, who has three children, had discovered her kidneys were failing in 2011, when a patient kicked her at work and her leg swelled dramatically. She started on dialysis three times a week, for four hours each time, draining her energy. It became hard to do the physical labor required at her job at a Veterans Affairs hospital, which she had loved.

So she was thrilled and relieved when she got the call, fittingly, during a dialysis session. The next day’s surgery went smoothly, and 11 days later, Ms. Glispy said she was doing well. She expressed gratitude as she recalled her worst fears during her years of treatment.

“I feel very fortunate, especially after watching so many people pass being on dialysis,” she said. “I’m seeing a lot of people die and I’m like, ‘It’s taking so long, it might not happen for me either.’”

Dialysis can be taxing on the body and does not cure kidney disease. Life expectancy for patients on dialysis varies greatly, but the average is five to 10 years, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Kidney transplants can improve life expectancy and quality of life, but many people who get one eventually need another.

The United Network for Organ Sharing, which manages the American transplant system, says that although the need for organs still far exceeds supply, donations are at historic highs. From January to March of this year, 9,500 transplants were performed, from 4,500 donors.

But there are still about 75,000 people who are cleared to have surgery and are waiting for organ donations. Including those not currently eligible for surgery, more than 113,000 people are waiting for organs.

The shortage of organs has lethal consequences. In 2017, the agency said, more than 6,500 candidates died while on the wait list, or within 30 days of leaving the list for personal or medical reasons without receiving a transplant. That makes the notion of an organ becoming less healthy during transit all the more galling, Dr. Scalea said.

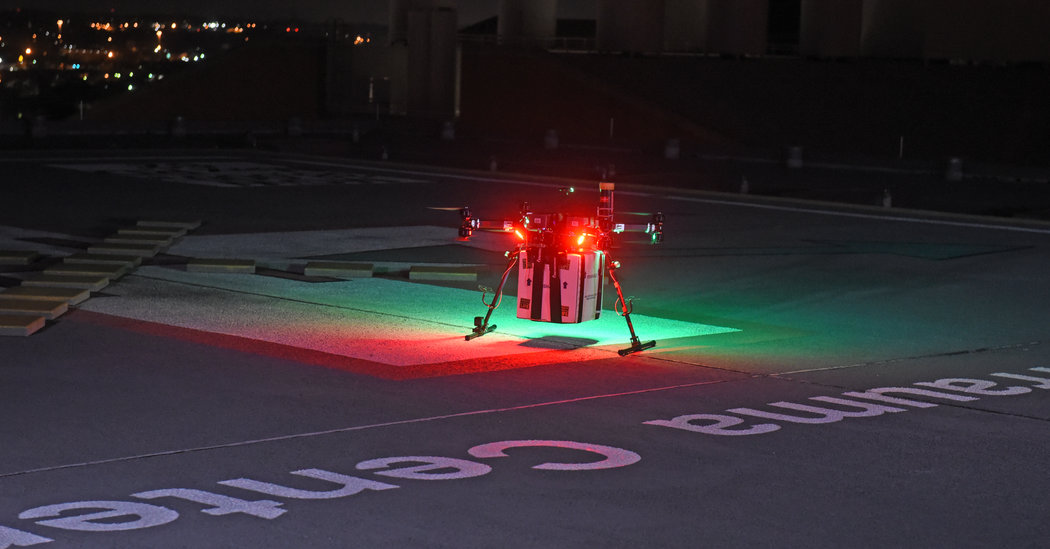

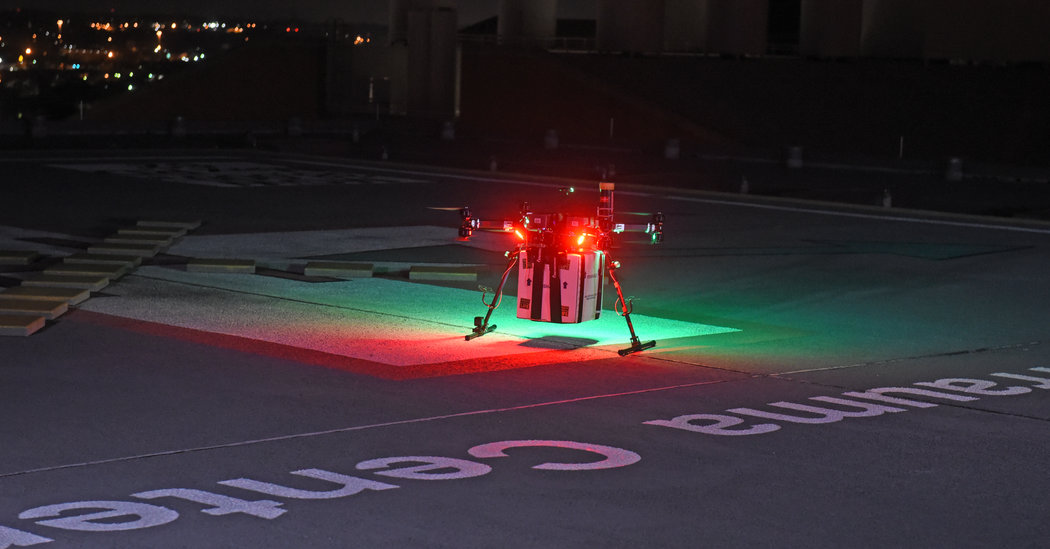

The drone used in this month’s test had backup propellers and motors, dual batteries and a parachute recovery system, to guard against catastrophe if one component encountered a problem 400 feet in the air. Two pilots on the ground monitored it using a wireless network, and were prepared to override the automated flight plan in case of emergency. The drone also had built-in devices to measure temperature, barometric pressure and vibrations, among other indicators.

Dr. Scalea called the flight “proof of concept that this broken system can be innovated.”

He added that current organ transport is “data-blind,” meaning doctors often cannot see an organ’s progress in transit. The drone allows timely updates on its progress, the way you might track an approaching taxi on your phone.

“We can monitor in real time,” Dr. Scalea said. “It’s like Uber for organs.”

The drone flew over 700 hours in 44 test flights before this journey, he added. The exercise allowed the team to overcome logistical and regulatory hurdles involved in transporting a viable organ, and it will now focus on flying “farther and faster,” he said.

Dr. Christopher Marsh, the director of the transplant program at Scripps Green Hospital in La Jolla, Calif., and a member of the American Society of Transplantation, said it was too early to pass judgment on the reliability of delivering organs by drone. But surgeons would be keeping a close eye on developments, he said.

Dr. Marsh, who was not affiliated with the test, noted that the technology could be helpful to avoid traffic in big cities.

“We’re entering a new world,” he said. “Things change, so we have to be open to that.”