Episode 11: ‘The Six Million Dollar Claim’

Producer/Director Suzanne Hillinger

Patients suffering from rare diseases who had little hope for a treatment now have access to life-changing medicines, thanks to pharmaceutical companies’ investment in so-called orphan drugs, which treat diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people. But the increasing number of people who would benefit from these treatments may not be able to afford the stunningly high prices, which can reach far beyond $1 million a year.

Reed Abelson and Katie Thomas, who cover the health care and drug industries, examine one ultra-costly drug that threw a union health plan into a crisis as it struggled to pay for an Ohio family’s prescriptions. Reporting for “The Weekly,” Reed and Katie found that pharmaceutical companies hold most of the power to set their own prices, and desperate patients and their health plans have few options and little recourse.

As treatments for rare diseases become more available, costs are skyrocketing and the health care industry is racing to find ways to provide promising new drugs to many more people.

Reed Abelson covers the business of health care for The New York Times, where she’s been a reporter since 1995. Reed writes about health insurance, how financial incentives affect the quality of care people receive and how health care has changed since the Affordable Care Act. Follow Reed on Twitter at @ReedAbelson.

Katie Thomas also covers the business of health care, with a focus on the drug industry and the high price of prescription drugs. Before she began writing about health care in 2012, Katie wrote investigative stories for the Sports desk about issues like gender equity in high schools and colleges, and whether student athletes should be paid. She also covered the Beijing and Vancouver Olympics. Follow Katie on Twitter at @katie_thomas.

Reed and Katie’s Top 3 Takeaways

The most expensive drugs are often the ones you’ve never heard about. Strensiq, which treats a rare genetic condition, has cost some health plans $2 million a year per adult, a price tag no one expected when it was approved in 2015. Many drugs to treat rare diseases are priced according to the weight of a patient. In the case of Strensiq, the initial estimates were based on the weight of a child, whose dosages would thus be much cheaper.

Rare diseases aren’t that rare. An estimated 30 million Americans have a rare disease, about the same amount as people living with diabetes. And though most rare diseases have no treatment, more drugs are coming to market. These new drugs can cost hundreds of thousands — sometimes millions — of dollars to treat one patient, raising questions about how we, as a society, will pay for them and who will get access to them.

Drug prices are a hot topic in Washington and on the presidential campaign trail, with Republicans and Democrats promising to tackle the high cost of prescription medicines. Yet most of the debate has centered on efforts to lower the cost of mass-market products like insulin, which is expensive, but not in the same ballpark as most rare-disease treatments. Companies that make drugs for rare diseases typically have little competition and can set whatever prices they choose.

Where Are They Now?

Dawn Patterson briefly stopped taking Strensiq in May, after she had a bad reaction from an injection. Symptoms from her condition returned when she was off the drug, and she resumed taking Strensiq about a month later. Her son, Will, graduated from high school and will attend Adrian College, in Michigan, in the fall. Melissa is working part time washing dishes at a restaurant and takes Strensiq three times a week.

Lori Jasperson, chief executive of the Boilermakers National Funds, is working with Express Scripts, the plan that covers her members’ prescription drugs, to develop new programs to reduce the union’s costs. The union is also being more cautious about approving new drugs for its members.

Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat from Oregon, released details in July of a bipartisan proposal to reduce prescription drug prices with Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa, who is the Republican chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Debate over the proposal is expected to continue when Congress returns this fall.

Dr. Steve Miller is the chief clinical officer of Cigna, which owns Express Scripts, the company that manages Dawn’s prescription plan. After The Times, Express Scripts and the Boilermakers Funds questioned the price of Strensiq, the drugmaker Alexion said it would cap the price of Strensiq at $1.5 million a year for adult patients covered by Express Scripts’ commercial health plans. The drug industry argues that high prices are necessary to encourage companies to invest in drugs for rare diseases.

Show Notes

Behind-the-scenes commentary about the episode

-

Image

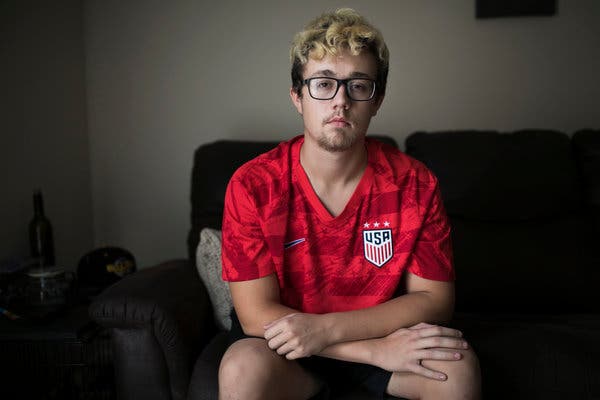

CreditCreditSuzanne Hillinger for The New York Times Katie Thomas went to Perrysburg, Ohio, to film with the Patterson family. Bill Patterson works as a boilermaker — “the best building trades craft there is,” he said.

CreditSuzanne Hillinger for The New York Times

Complete Coverage

Senior Story Editors Dan Barry, Liz O. Baylen, and Liz Day

Director of Photography Victor Tadashi Suarez

Video Editor Geoff O’Brien

Associate Producer Abdulai Bah