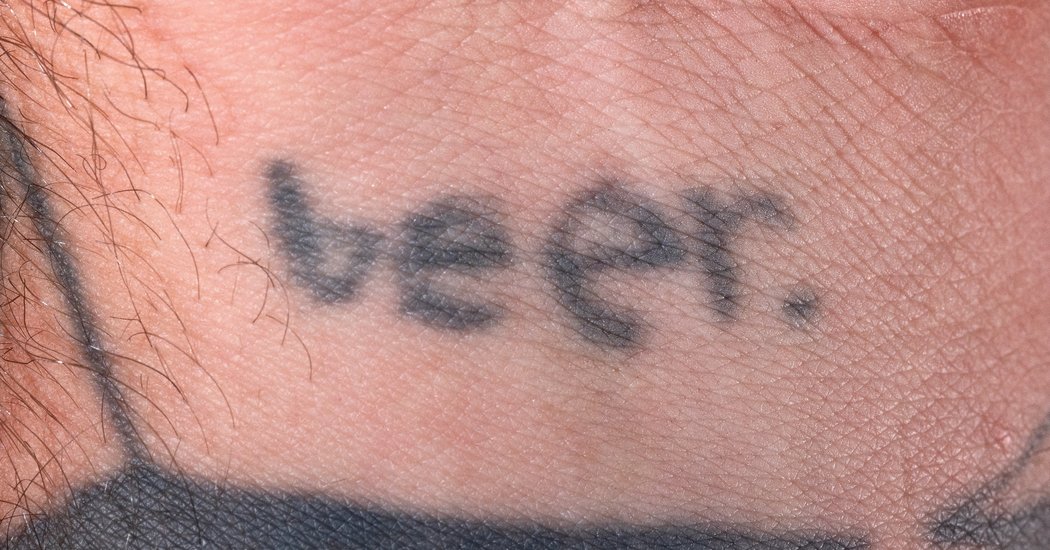

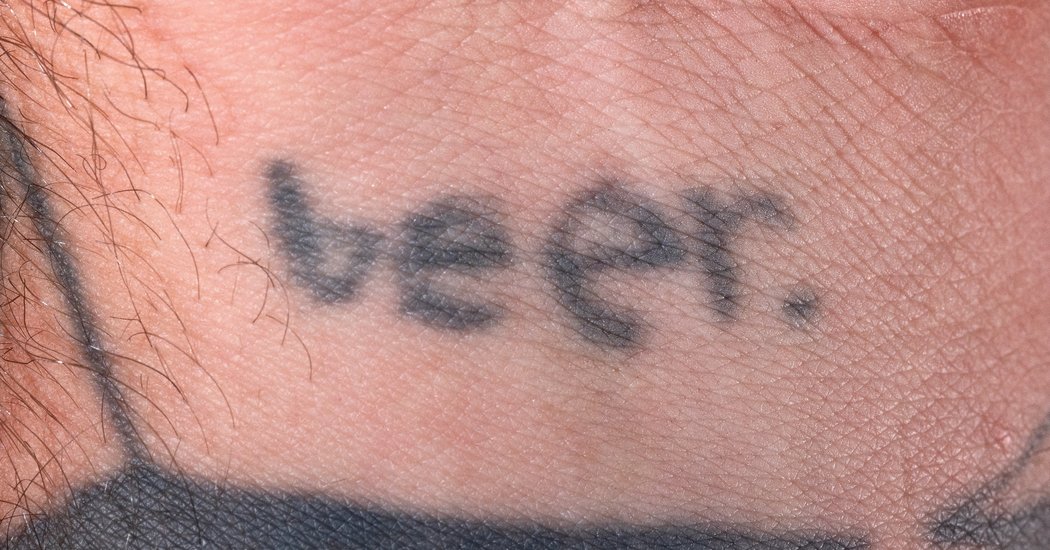

A few years ago, a friend of mine who teaches at a college in upstate New York went to the doctor for a checkup. He’s a big guy, and he removed his blazer and XXL oxford shirt to reveal his torso, which is festooned with homemade tattoos. On his forearm is one I gave him years earlier in a Mexico City hotel room, simply spelling out “HEY.” Beneath his left breast is a tombstone inscribed with his initials and the epitaph “Live Fat. Die.” Once, he inked on his own wrist, in the place where you’d slice the artery if you were suicidal: “beer.”

The doctor was speechless, until finally he asked, “You’re a professor?”

“A lot of things had to happen,” my friend replied, “for me to be me.”

Unlike professional parlor tattoos, which are now so respectable that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada has one (a Haida raven on his left shoulder), stick-and-pokes still retain an air of the illicit. I have a mess of homemade tattoos all over my body — not as many as my professor friend, and none of them quite as ridiculous, but like his, they’re all essentially random. Over the years, they’ve become only more absurd and more ubiquitous, spreading out across my arms, my chest, my feet — vandalism on the decrepit temple that is my 36-year-old body. There’s the jabberwocky phrase on my shins, “upthe monkeys” [sic]; there’s the triangle with eyeballs on my left forearm; there’s the man in a hat smoking a cigarette on my right shoulder, which my professor friend gave me in that same Mexico City hotel room using tequila as an antiseptic (and artistic inspiration).

These tattoos are like a car crash: so ugly you can’t look away. Sometimes people stare and ask how they happened, what it all means. And yet there’s nothing to explain. The inscrutability is part of the appeal: I enjoy when people inquire, and I enjoy not answering, which is different from not actually caring if they ask or wonder. There is power in saying no.

If I were to indulge the curious, though, I’d probably say something about how stick-and-pokes are meaningful precisely because they look so bad. What’s important is the process, not the result — deciding at 3 a.m. that you suddenly, desperately need, say, a paisley sock tattooed on your foot, and enlisting a friend to immediately indulge that desire. The genius of the idea may be fleeting, but the result is forever, and therein lies the fun: It’s a modern-day bonding ritual, an initiation into a version of adulthood in which nothing is too sacred to laugh at, especially yourself. The image itself is mostly beside the point.

Admission to the tribe comes cheap. A stick-and-poke kit costs about $10, and you can find it all at Walmart: “India black” calligraphers’ ink, a needle and sewing thread. First, you boil the sewing needle and blacken the tip over a Bic flame. This should, in theory, sterilize it. Then affix the needle to the butt end of a pencil by wrapping sewing thread around the needle and the pencil to hold them together. The thread should reach almost all the way to the needle’s tip, so it can soak up the ink, leaving enough of the point exposed to pierce the skin. The ink-sopped thread comes into contact with the wound, and voilà, you have a tiny ink dot under your skin.

The design should be simple, because every line you make must be drawn by stabbing an area over and over again to connect two points. The skin scars over the line, sealing it in the dermis, your second layer of tissue. Some people freehand their graphics, but I prefer to first draw the desired image with a fine-tip Sharpie. The marker eventually rubs off, but the skin becomes so perforated that you just trace the raised moguls of irritated flesh, fingering them like Braille. The blood is a central part of the high, too. Stick-and-pokes provide an inkling of the same excitement and intimacy of a one-night stand — an approximation of the bleary fun of waking up and thinking, What in the world did I do last night?

Professional tattoo parlors often warn customers: If I can’t be drunk while I give you this tattoo, you can’t be drunk, either. But that spirit is anathema to the stick-and-poke. You should at least have a few drinks before you get or give one, in part to celebrate your admission to this not-so-exclusive club — and in part to numb the pain. One night, a friend was halfway through working on my chest when we ran out of beer. I quickly sobered up, and each time the needle struck the skin it hit a nerve, sending my left arm skyward with agony.

The friend who gave me that tattoo received a cancer diagnosis recently, and it’s not the kind that typically goes into remission. He, my professor friend and I grew up together, and our bodies bear one another’s handiwork. The tattoo he gave me on my chest is smudgy and faded and looks like a mistake. I won’t tell you what it depicts, and I wouldn’t explain it if you happened to see me with my shirt off, but that’s beside the point: Like all homemade tattoos, it’s a flamboyant declaration that a lot of things had to happen for me to be me. Some of those things were ugly, some were self-destructive, some were tragic. Stick-and-pokes are the scars from a life lived intensely but not too seriously. The images may not make sense, but that doesn’t mean they’re meaningless.