Dr. LaSalle D. Leffall Jr., a surgeon and educator who as the first black president of the American Cancer Society was a leader in promoting awareness of the risks of cancer, particularly among African-Americans, died on May 25 in Washington. He was 89.

His son, LaSalle Leffall III, said Dr. Leffall himself died of cancer at a hospital.

A son of the small-town, segregated Florida Panhandle, Dr. Leffall was also the first black president of the American College of Surgeons in 1979 and the first black person to head the Society of Surgical Oncology and the Society of Surgical Chairs.

In 2002, President George W. Bush appointed him chairman of the President’s Cancer Panel, an influential advisory role that he held until 2011. He also served as chairman of Susan G. Komen, the breast cancer foundation.

As president of the American Cancer Society, beginning in 1978, Dr. Leffall launched a campaign to promote early diagnosis and other preventive measures to reduce the higher rates of lung, stomach, pancreatic and esophagus cancer among black men and uterine cancer among black women — diseases attributed in part to social and environmental factors, like insufficient access to health care and exposure to industrial carcinogens.

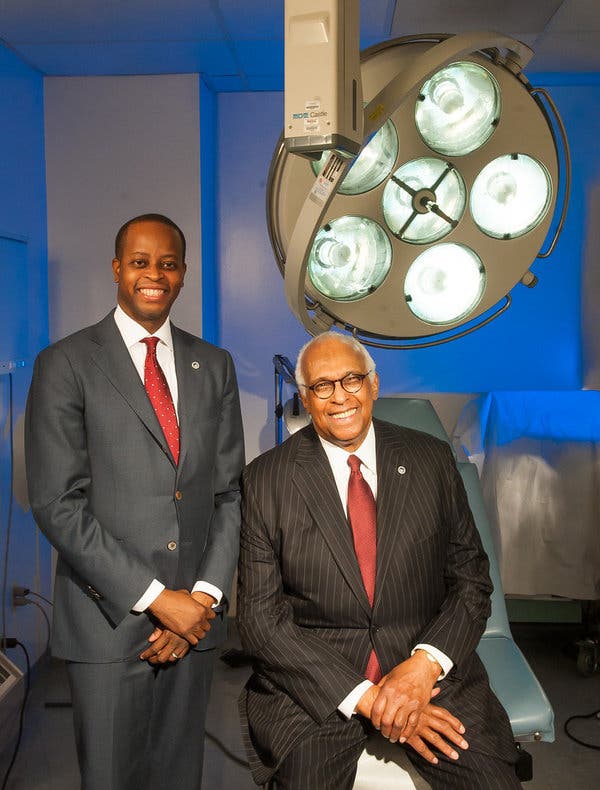

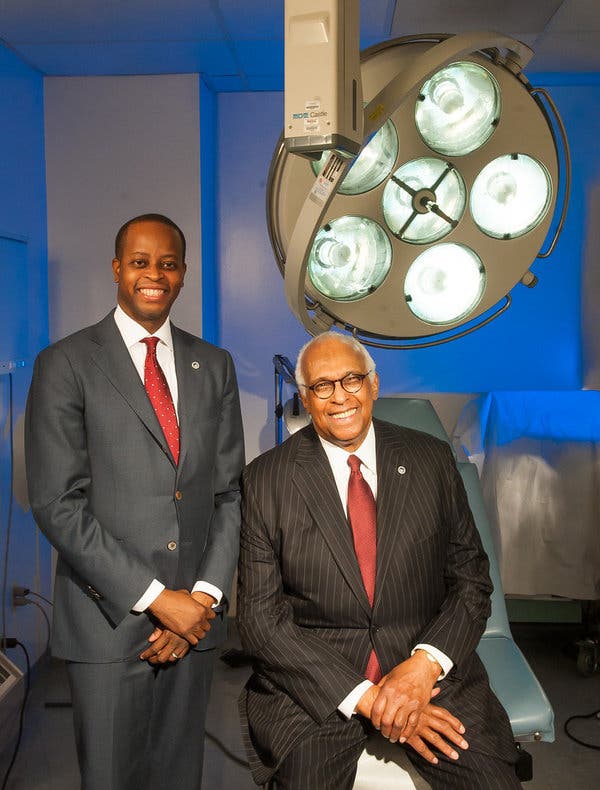

Dr. Wayne A. I. Frederick, who studied under Dr. Leffall and became the president of Howard University, where Dr. Leffall chaired the medical college’s department of surgery for 25 years, described him in a statement as “a surgeon par excellence, oncologist, medical educator, civic leader and mentor, to me and so many others.”

Dr. Leffall, who began teaching at Howard in 1962, estimated that he had trained about 6,000 of Howard’s future physicians and hundreds of prospective surgeons.

He would remind his protégés of the value of education and of the pressures he felt as a black man never to be considered second-rate.

“I can’t afford ever to do less than the best,” he told The Washington Post in 1979. “I don’t mind being the first, but I don’t want to be the only.”

Dr. Leffall performed surgery until he was 76, practiced medicine until he was 83 and remained on the Howard faculty as a lecturer until his death.

LaSalle Doheny Leffall Jr. was born on May 22, 1930, in Tallahassee, Fla., on May 22, 1930. His father taught agriculture at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College (now University) and was later a high school principal. His mother, Martha (Jordan) Leffall, was also an educator. He was raised in nearby Quincy.

“With a good education and hard work, combined with honesty and integrity, there are no boundaries,” Dr. Leffall recalled his father telling him. To which his son would respond skeptically, “You shouldn’t be saying that, because look, I see things,” like local movie theaters that either barred black people or forced them to sit in balconies.

Dr. Leffall, right, with Dr. Wayne A.I. Frederick, the president of Howard University, in an undated photo. Dr. Frederick called him “a surgeon par excellence, oncologist, medical educator, civic leader and mentor.”CreditHoward University

“You would ask questions about why,” he said, in an interview for the National Library of Medicine in 2010. “They would say, ‘Well, this is not right, but that’s the I way it is.’ ”

His godmother’s husband was a doctor, the only black physician in Quincy. But what committed Dr. Leffall to a medical career was an experience he had at 9 years old, when he nursed an injured bird back to health. He placed the bird’s leg in a splint made of tongue depressors, and within three days the bird could fly away.

“I believe that, more than any other experience, influenced me,” Dr. Leffall said.

In 1948, after finishing high school at 15, he graduated in three years from Florida A&M, where he majored in biology and minored in English, and, with a boost from the college president, was admitted to Howard University College of Medicine. He graduated first in his class.

Dr. Leffall completed his surgical oncology training at what is now Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and specialized in colorectal, breast, and head and neck cancers.

In 1956 he married Ruth McWilliams, who survives him, along with their son, who goes by Donney, and Dr. Leffall’s sister, Dolores C. Leffall.

Before being deployed overseas with the Army Medical Corps, Dr. Leffall was assigned to Texas, where he and three white fellow soldiers went to the movies one day. An attendant refused to admit him.

“Of all the things I have experienced, I think that hurt worse than anything else,” he recalled in a 2013 interview with the American College of Surgeons. “Here I am, on my way to help the men and women who are defending our country, and I can’t go to a movie with my colleagues.”

He was discharged as a major after serving as chief of general surgery at the Army hospital in Munich.

He was named a full professor at Howard in 1970. In 1992, he was appointed Charles R. Drew professor of surgery, a position named for a pioneering black surgeon. In 1996, Howard established a professorship in Dr. Leffall’s name. He wrote a memoir, “No Boundaries: A Cancer Surgeon’s Odyssey,” in 2005.

An avid tennis player and jazz enthusiast (he was a friend of the saxophonist Cannonball Adderley), Dr. Leffall was also a language maven. He was quoted in William Safire’s New York Times column in 2001 distinguishing between an operation, a procedure and surgery.

“Every operation is a procedure, but not every procedure is an operation,” Dr. Leffall said. “You can say ‘a surgical procedure,’ but it would be redundant to say ‘a surgical operation.’ ”

In 2013, Dr. Leffall told The ASCO Post, a newspaper in partnership with the American Society of Clinical Oncology, that survival rates and quality of life for cancer patients overall had progressed during his 65 years in medicine, but that his hope was to eliminate the disease altogether.

“With ongoing basic and clinical research, we will continue to make progress that could eventually lead to a universal cure for cancer,” he said. “When that happens, I’ll applaud from Heaven.”