LOS ANGELES — Kim Gordon is synonymous with New York.

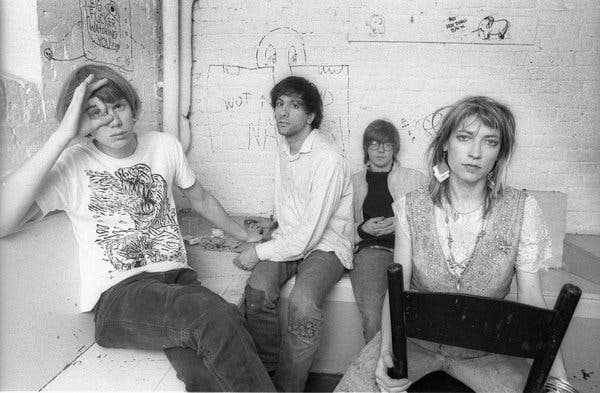

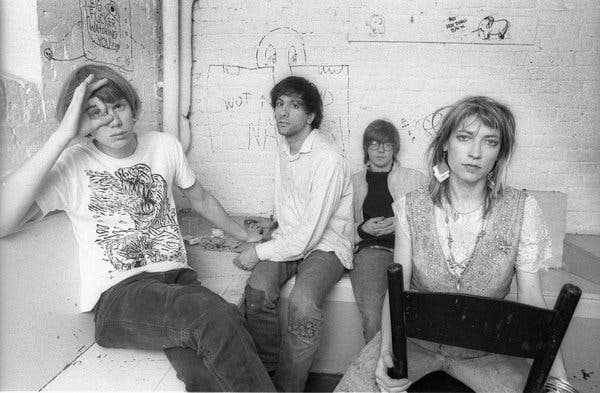

It was in New York that Ms. Gordon, helped found Sonic Youth, probably the most influential New York art-rock band since the Velvet Underground.

It was in New York that Ms. Gordon became a fashion influencer, blending 1980s thrift store campiness with 1960s Anita Pallenberg mod.

And it was in New York that Ms. Gordon achieved hipster emeritus status, a personification of downtown cool captured forever in freeze-frame, icily staring out behind dark glasses against a graffiti-strewn brick wall.

But that Kim Gordon does not exist anymore.

Nearly a decade removed from a rancorous split from Sonic Youth and her husband and bandmate, Thurston Moore, Ms. Gordon, 66, is a solo act in every sense of the term: an ex-rock star, an ex-wife and, yes, an ex-New Yorker.

Ms. Gordon is now a full-time artist and sometimes-musician, living in a four-bedroom house in the Franklin Hills section of Los Angeles, some 2,800 miles from the city that enshrined her.

Her handsome hillside home is decorated in a tasteful West Coast style, with tattered Moroccan rugs scattered on blond oak floors, midcentury furniture and artwork by friends like Christopher Wool, Rita Ackermann and Richard Prince.

Her house is also filled with framed photos of her daughter, Coco Gordon Moore, 25, an artist and poet living in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn.

What’s missing — aside from a footstool emblazoned with the black-and-white illustration from Sonic Youth’s 1990 major-label debut, “Goo” — is any visible reminder of the band that made her famous. Or the man she became famous alongside.

On a recent visit to her Los Angeles home, a few weeks before her first solo album, “No Home Record,” drops, she summarized her thoughts on Sonic Youth and Mr. Moore, in three short words.

“I’ve moved on,” she said.

Lost Angeles

“California is a place of death, a place people are drawn to because they don’t realize deep down they’re actually afraid of what they want,” Ms. Gordon writes in her 2015 autobiography, “Girl in a Band.”

That may sound like a rather gloomy New York take on sunny Los Angeles, but they are notes of a native daughter. Ms. Gordon grew up in Los Angeles, and on a cloudless August morning, with temperatures pushing 90, she was steering her black Toyota Prius through eastern Hollywood on a tour of her reclaimed city.

“I always feel like wherever I am, I sort of take that energy on, and I was a little worried that I wouldn’t be motivated enough in L.A.,” Ms. Gordon said, as the Prius lurched through weekday traffic.

She was dressed in an earth-tone blouson dress with hints of tie-dye and shimmery gold sandals that showed off her lemony toenail polish, but it would be a stretch to call her “sunny.” Yet neither was she the aloof subject that came across in piles of magazine interviews during the Sonic Youth years, in which she tended to defer to her professorial husband, standing by like a rock ’n’ roll sphinx.

Now, she smiled easily and in Southern California fashion, tended to punctuate sentences with a girlish giggle, even when no joke was uttered. But she was vastly more comfortable talking in abstraction, particularly about art, than about herself.

“There was no center, so there was no gravitational pull,” she said, as her hybrid car fell silent at a stoplight. “In New York, you can just feel the buzz of activity around you. Even if you’re not yet participating, you kind of feel like you’re doing stuff. It was sort of comforting to me as a sort of restless soul.”

Born in Rochester, she moved to California when she was 5 after her father, a sociology professor, took a job at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Coming of age when the age was Aquarius, she recalls sitting around in her suburban-like bedroom painting, smoking pot and listening to Joni Mitchell as she dreamed about the creative ferment of Laurel Canyon, the Valhalla of Los Angeles rock where Ms. Mitchell, along with the likes of Cass Elliott (Mama Cass) and Neil Young, lived.

But New York was where the art was, and Ms. Gordon, who graduated from the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, knew she had to be there. “I felt painfully middle-class,” Ms. Gordon said. “I hate the phrase ‘reinvent yourself,’ but it was kind of like I had to live in New York to become who I always wanted to be.”

She arrived at an auspicious time. In 1980, New York was still chaotic and dangerous — even TriBeCa was a little dicey — but if you made it to the Mudd Club on White Street in one piece, you could rub shoulders with Lou Reed, Debbie Harry or Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Ms. Gordon shopped for Warhol superstar outfits at the Patricia Fields boutique on Eighth Street and learned to play bass from artist friends like John Miller. She worked in the office of Larry Gagosian, when he was starting out as an art dealer, and once, when she was at Jenny Holzer’s apartment, a woman she just met gave her a beat-up Drifter guitar.

Not long afterward, a very tall musician named Thurston Moore, whom she knew vaguely, dropped by her Eldridge Street apartment and said, “I know that guitar.” Her life as an artist was about to take a very long detour.

But that was a different time in her life, and after Giuliani, Bloomberg and a tsunami of Wall Street money, that New York is no more. As she writes in her book: “That city I know doesn’t exist anymore, and it’s more alive in my head than it is when I’m there.”

The Los Angeles she has returned is also very different from the one she left in 1980: For one thing, the city is awash with expat artists and designers from New York who are seeking a creative paradise under the sun.

After touring her hillside home, she wanted to head over to MacArthur Park to visit a space shared by the art galleries Reena Spaulings Fine Art and House of Gaga for a show featuring works by Jill Mulleady and Larry Johnson.

But as she drove down Normal Avenue, she pulled the Prius over in front of a Virgil Normal. It calls itself a “gender fluid lifestyle” boutique and sells skater-inflected clothing by indie designers. With its ironic sweatshirts, designer baseball caps, and kitschy 1970s curios, it feels like a 2019 update on the funky boutiques of the East Village in the 1980s.

“It’s quintessentially L.A., in the best sense,” Ms. Gordon said. “It supports a lot of young people in their endeavors with free-form small events that don’t feel commercial. It feels spontaneous.”

“New York,” she said, “feels like one big shopping mall.”

Seeking Bohemia

Her breakup with New York was not the only reason she left.

Even before the Sept. 11 attacks, Ms. Gordon and Mr. Moore were bouncing between a loft on Lafayette Street in SoHo and a house in Northampton, Mass., where they moved to raise their daughter away from New York pressures.

The end of their marriage came quickly.

As she recounts in her memoir, she grew suspicious that her husband was seeing another woman when a friend noticed that he had switched cigarette brands. Before long, Ms. Gordon was finding intimate text messages. She confronted him. They tried counseling. It was not enough.

By late 2011, in what would turn out to be Sonic Youth’s final concert, the stage in São Paulo, Brazil, reminded Ms. Gordon of a kitchen where “the husband and the wife pass each other in the morning and make themselves separate cups of coffee,” she writes, “with neither one acknowledging the other, or any shared history, in the room.”

A marriage of alt-rock’s first couple was over. (“Whyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy!” wrote Jon Dolan, a rock critic for Grantland, capturing the collective angst of Sonic Youth fans.)

Her memoir, a highly out-of-character tell-all, was in part an attempt “to figure out how I got to where I was in my life,” she said.

But there was a more practical reason. “I had to find another way to make money,” she said, “because when the band broke up, it was my primary source of income.”

After the book came out, she considered that chapter closed. She would not be talking about her husband anymore. And indeed, over the course of that day, she mentioned him only once, albeit rather affectionately, in a conversation about wearisome questions from journalists.

(“People doing interviews would always say, ‘So the name is Sonic Youth. You’re how old?’ Thurston always had a good comeback: ‘Well, the Rolling Stones aren’t literally ‘rolling stones.’”)

With her marriage and the band over, and her daughter out of college, there was a lot less keeping her on the East Coast. A move to Los Angeles would provide a clean break and a new adventure.

She considered Venice Beach, where she had lived in the early 1970s, but it was losing its bohemian edge, she said (“You have tech companies taking over.”) After an Airbnb stay in Echo Park (“a little too hipster-ish”), she settled on Franklin Hills in Los Feliz, where she bought a 1930s “mullet style” home (one story in front, two stories in the rear).

She redid the kitchen and front garden, added two rear decks with views of downtown Hollywood, and furnished it with new items. “I didn’t want to bring stuff,” she said.

Los Angeles also offered a blank canvas to create art.

Although Ms. Gordon has worked as an artist since the 1970s (her first solo exhibit was at White Columns in New York in 1981), she showed sporadically throughout the 1990s and 2000s, and is now represented by 303 Gallery in New York.

A solo show earlier this year at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, “Lo-Fi Glamour,” featured graffiti-like paintings scrawled with gut-punch slogans like “#You Don’t Own Me.” It closed this month.

And currently on view at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin is “She Bites Her Tender Mind,” which uses Ms. Gordon’s recent Airbnb stays in Los Angeles to meditate on the meaning of home (a subject she also explores on the new album with her song “Airbnb”).

“People are looking at this utopian weekend getaway as trying on a different lifestyle,” she said. “It appeals to a fantasy. It’s like a clean slate.”

After the detour at Virgil Normal, Ms. Gordon parked the car near MacArthur Park in Westlake a neighborhood that has seen the arrival of luxury lofts, restaurants and, yes, galleries. Gentrification is a topic that figures prominently in her work.

“It’s unfortunate that artists are often on the front lines of gentrification, because they’re looking for cheap places, too,” she said. “There really isn’t the money here,” Ms. Gordon added, as she perused works by Juliana Huxtable and Reynaldo Rivera in the soaring brick-walled gallery. “Hollywood money is not Wall Street money, to be quite crude about it.”

Indeed, artists in Los Angeles are freer to flourish, and fail — something that Ms. Gordon seems to appreciate.

“Sometimes I think the art here is more eccentric,” she said, before adding, “there is something nice about not being under a microscope.”

An Unwilling Icon

In the eight years since Sonic Youth broke up, Ms. Gordon has not missed the touring, the videos, the grind. It is hard to tell if she even missed the music.

“I never thought of myself as a musician,” she said. “Punk rock kind of pulls people in.”

As an artist, however, she felt that she still had something to say. Earlier this decade, she began collaborating with Bill Nace, experimental musician, on a project called Body/Head. Pitchfork described the duo’s 2013 album, “The Switch,” as a “sonic ecosystem” as “mesmerizing as a hypnotist’s swinging clock.”

When asked what she hoped to accomplish with “No Home Record,” her first solo album, due out on Oct. 11, she responded with an amused snort: “Uh, nothing?”

The nine-track album was recorded in the home studio of her producer Justin Raisen, known for his work with Santigold and Sky Ferreira, and could be seen as a coming to grips with her new life in Los Angeles.

No one is going to confuse the new album for a Beach Boys homage. The music is a swirling aural collage with splashes of vintage Sonic Youth noise rock, offset by jagged, impressionistic lyrics.

The song “Earthquake,” for example, merges a distinctly West Coast sense of dread with an unspecified relationship crisis (“If I could cry and shake/I’d lay awake, for you”).

With its references to hashtags and “shopping off a cliff,” “Get Yr Life Back” conjures images of the Instagram Pollyannas of Santa Monica, DM-ing toward the “end of capitalism.”

For lunch, Ms. Gordon suggested Restaurante Tierra Caliente, a no-frills storefront taqueria near Dodger Stadium that she said has the best mole tacos in Los Angeles.

“I could use a beer,” she said as she exited the car. A quick trip to a nearby bodega produced two bottles of Pacifico, and after pouring them furtively into Styrofoam cups, Mr. Gordon girded herself for more questions — this time about her legacy, pretty much the last topic that she ever wants to discuss.

Harper’s Bazaar once called her a “countercultural icon,” Vice crowned her an “art rock legend,” and the Los Angeles Times pronounced her a “beacon of feminist strength.”

What does she make of the accolades? “You end up feeling like you have impostor syndrome,” she said. “Being referred to as an ‘icon,’ blah blah blah. What does that even mean?”

Did cutting her first solo album, after decades in a major band, allow for more personal statements with her music?

“I don’t really look at it like that,” she said. “My priority is doing visual art.”

“In fact,” she added wearily, “what I was really thinking was, ‘Well, if I do an album, I’m going to have to do interviews.”