Kaiser Permanente reached a tentative deal with more than 75,000 of its health care workers Friday morning, a week after a three-day walkout that disrupted appointments and services at many hospitals and clinics.

The labor dispute was the latest in a series between health care organizations and their employees, many of whom cite exhaustion, burnout and frustration with severe staffing shortages that have persisted long past the worst of the pandemic’s crushing workload.

The proposed four-year contract would include significant wage increases, setting a new minimum of $25 an hour in California. The unions said the proposed wage hikes were essential to attracting enough workers to provide adequate staffing at Kaiser’s facilities. The agreement would raise the hourly rate to $23 in other states and would stagger a 21 percent increase in wages over four years. It also includes what the union described as important protections against Kaiser’s ability to outsource jobs.

“Millions of Americans are safer today because tens of thousands of dedicated health care workers fought for and won the critical resources they need and that patients need,” Caroline Lucas, the executive director of the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, which represents about half of Kaiser’s work force, said in a statement. “This historic agreement will set a higher standard for the health care industry nationwide.”

Kaiser officials also applauded the proposed settlement. They said in a statement: “The new four-year agreement will offer Coalition-represented employees competitive wages, excellent benefits, generous retirement income plans and valuable job training opportunities that support their economic well-being, advance our shared mission and keep Kaiser Permanente a best place to work and receive care.”

Kaiser and the unions both credited the involvement of Julie Su, the acting U.S. labor secretary, for helping broker the tentative deal. Ms. Su traveled to California Thursday night to rejoin the talks, and the proposed settlement was reached early Friday.

“I’m very happy, very elated, very exhausted,” said Georgette Bradford, an ultrasound technologist at a breast imaging center in Sacramento, who served on the union’s bargaining team. Ms. Bradford, 48, who has taken part in several contract negotiations over her 19 years at Kaiser, said this agreement felt particularly special because of the camaraderie across other sectors during what she referred to as a “hot labor summer.”

“That support from others in the community was never seen to this level before,” she said. “It was overwhelming.”

Union members will vote on whether to ratify the deal on Wednesday.

Kaiser Permanente health plans cover 13 million people in eight states through its own network of hospitals and doctors.

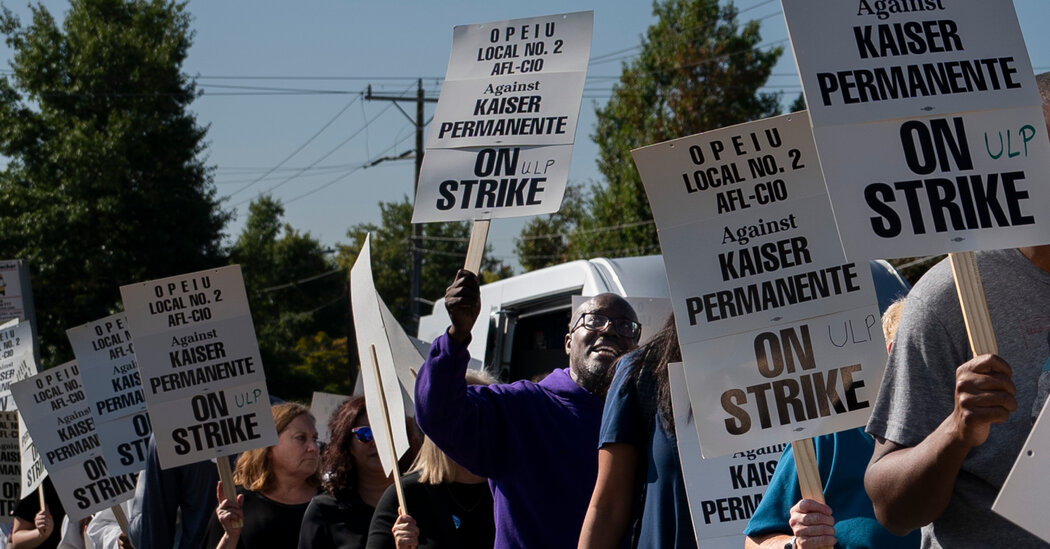

The 72-hour walkout that ended nearly a week ago put a lot of pressure on Kaiser sites, which had to operate without thousands of medical assistants, laboratory technicians, receptionists and sanitation staff members who formed picket lines outside dozens of its buildings.

The work stoppage forced Kaiser to move many appointments online and to postpone procedures that weren’t considered urgent, like colonoscopies or mammograms. The company brought contingency workers into hospitals and urgency care centers, but more than 50 labs in Southern California were shut down, and dozens of other facilities throughout the West Coast either closed or limited their hours. Union leaders called it the largest strike by health care workers in recent U.S. history.

Kaiser’s stalemate drew the attention of Ms. Su, who traveled last week to San Francisco during the strike to meet with officials from both sides of the negotiations. But talks broke off, with the labor coalition threatening a weeklong walkout for early November if the two sides could not settle a contract beforehand.

The deal reflects a pivotal moment in the health labor market, after a significant exodus of staff members throughout the industry has left the supply of workers far below the demand. The dynamic has created a sense of urgency on each side: Workers trying to treat patients amid staffing shortages report record levels of burnout, while their employers are under pressure to preserve their workforces and offer packages that attract new workers.

Analysts say the situation has most likely provided union workers with leverage to get more at the table, and many are seizing the opportunity. More than a dozen health worker strikes have taken place this year in New York City, California, Illinois, Michigan and elsewhere.

The settlement, particularly the agreement on a higher minimum wage affecting low-income employees, “will impact health care workers outside of Kaiser,” said John August, who was the executive director for the coalition of Kaiser unions until 2013 and is now a program director at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. “It’s a great pressure point for the rest of industry, for sure,” he said.

About 1,500 health workers began a five-day strike against Prime’s St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood, Calif., on Oct. 9, citing dangerous short-staffing practices. Pharmacy staff workers at some Walgreens stores in Oregon, Washington, Arizona and Massachusetts walked out on the same day, citing workloads so excessive that they could not safely fill prescriptions. Without a formal union, they organized on Facebook and Reddit.

The New York State Nurses Association entered a new contract with Mount Sinai Hospital, which includes an enforcement mechanism for nurse-patient staffing ratios.

But companies like Kaiser are under pressure to limit their expenses, and the organization emphasizes that it needs to make sure its care is affordable. The organization, which had operating revenue of $95.4 billion, reported an operating loss of $1.3 billion in 2022. In recent months, Kaiser has returned to profitability.