The tobacco giant Altria, maker of Marlboro and other top-selling brands of cigarettes, has agreed to pay nearly $13 billion for a 35 percent stake in Juul Labs, the wildly popular vaping company that burst on the scene in 2015 with a mission to render cigarettes obsolete.

To sweeten the deal, part of Altria’s investment involved giving a bonus of $2 billion to Juul’s 1,500 employees, with the exact amount dependent on the length of employment and how much stock they own in the company, which has a valuation now of $38 billion.

The all-cash deal, approved late Wednesday by the company boards and announced before the opening of stock trading Thursday, pairs two businesses whose products have had a profound effect on public health, and, until now, had seemingly divergent paths.

Altria, the parent of Philip Morris U.S.A., which for decades denied the fact that cigarettes cause cancer and other lethal illnesses, is desperate to keep its hold in a declining cigarette market. Juul, a San Francisco start-up, has tried to position itself as offering a safer alternative to combustible cigarettes — but has ended up vilified for the sharp rise in vaping and nicotine addition among teenagers who have never smoked.

[Read what we know about the health effects of e-cigarettes.]

Now Juul is staking its future growth on the very industry it sought to disrupt, while Altria can profit from, and even influence, its would-be slayer.

“We understand the controversy and skepticism that comes with an affiliation and partnership with the largest tobacco company in the U.S.,” said Kevin Burns, chief executive of Juul in a statement Thursday morning. “We were skeptical as well.”

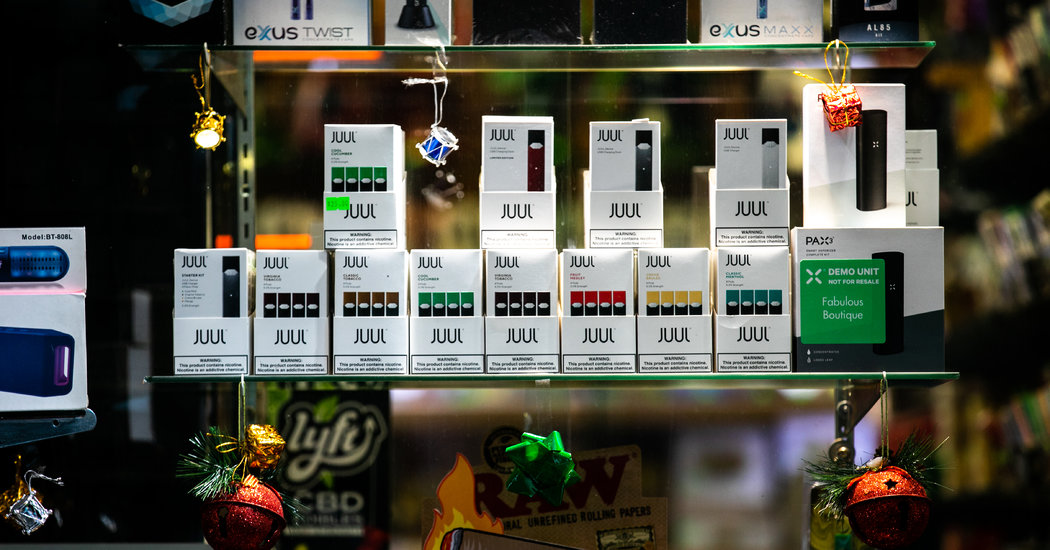

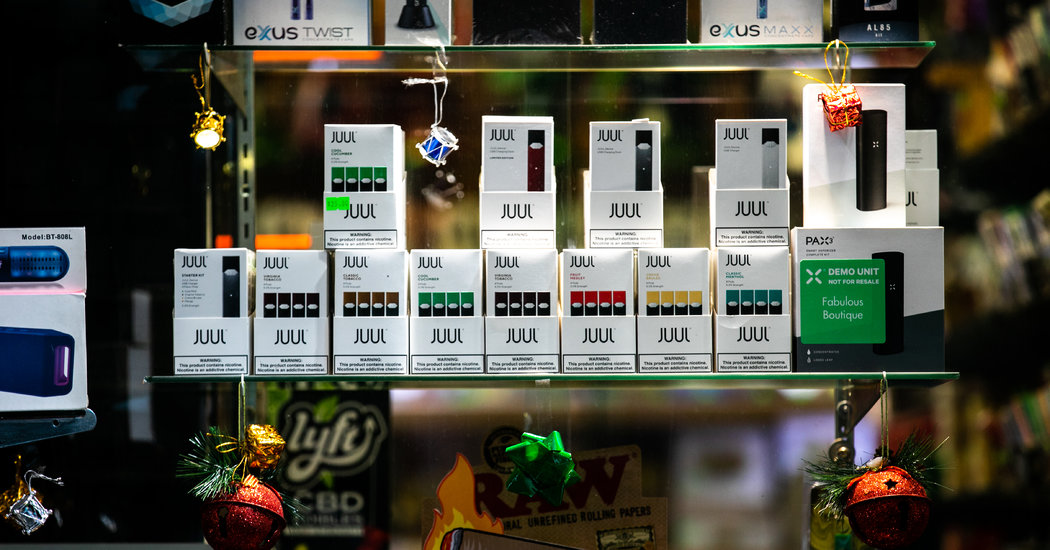

Under the terms of the deal, Altria will get a 35-percent stake in the proceeds from Juul vaporizers and nicotine pods, which have captured more than 70 percent of the United States e-cigarette market in just a few years in business.

In exchange, Juul will get access to Altria’s marketing and distribution muscle, including prized shelf space in convenience stores, but also Altria’s lobbying power and regulatory influence. During the past year, Juul has confronted one public relations disaster after another as its sleek, high-nicotine e-cigarette became the drug of choice for the nation’s youth and the target of federal regulators, parents and school officials.

In a call with investors and analysts Altria’s chief executive, Howard Willard, said his company was ready to help Juul take on the Food and Drug Administration.

“We have years of experience and literally hundreds if not thousands of interactions with the F.D.A. that we’d be happy to provide perspective on,” he said.

Juul is also gambling that other terms Altria agreed to will overcome public mistrust of the deal — including an agreement to allow Juul to advertise its product to smokers through package inserts in Altria’s cigarettes.

The deal comes as the F.D.A. escalates its crackdown on Juul and other e-cigarette makers. The agency’s commissioner, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, was initially a strong advocate for these new products, but has initiated a campaign to limit their reach now that youth vaping has soared.

The F.D.A. has been investigating Juul for months, and threatened to pull the devices off the shelves if the company couldn’t find a way to keep them away from teenagers. At the same time, Dr. Gottlieb is pushing to reduce nicotine in traditional cigarettes to nonaddictive levels, although Altria and other tobacco companies plan to fight the agency on that issue.

With this deal, Juul “suddenly has the resources to refocus from defense to offense,” said David Sweanor, an antismoking advocate who supports using electronic cigarettes as an alternative. “Instead of just trying to survive an onslaught from F.D.A. regulators and abstinence-only campaigners creating a moral panic about their product, they can move to rapidly expanding with a global orientation and funding the R&D necessary to disrupt ever more of the $800 billion global cigarette market.”

To counter the mounting criticism of its product, Juul has spent months hiring public relations firms and lobbyists to try to persuade regulators that the soaring teenage use was an accident, not a deliberate marketing strategy. Juul changed the name of some of its flavors, took others out of stores and secured the services of Washington’s best-connected lobbyists and image consultants.

Any progress in improving its image among public health advocates may be greatly diminished with this deal.

“I think it is beyond question that if Altria acquired a substantial interest in Juul, it would dramatically alter the perception that this was a company whose goal was to reduce, if not eliminate, the use of cigarettes,” said Matthew L. Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “Altria has no interest in seriously reducing the number of people who smoke cigarettes.”

Rather, he contended, Altria sees Juul’s e-cigarettes “as their fail-safe in case the cigarette market keeps declining so that they remain profitable no matter what happens.”

Industry analysts seemed positive about the union. Bonnie Herzog, of Wells Fargo Securities said in an email that Altria’s infrastructure, logistics, sales and distribution strength would be an advantage for Juul. Ms. Herzog also said that she would have expected Altria to have more control of the company than it ended up with.

For Altria, the stake in the popular e-cigarette provides a counterweight to its disappointment at the F.D.A.’s lack of approval for IQOS, the heat-not-burn e-cigarette device made by Philip Morris International, which Altria was expecting to distribute in the United States. Without that product, Juul has had even more time to capture the e-cigarette market. Mr. Willard, however, said Altria was still eager to sell IQOS and believed the F.D.A. would permit its sale.

Altria could see a steep decline in its profits if nicotine was limited in combustible cigarettes. And Altria, for its part, has every reason to pressure Juul to resist such regulations. That’s because Altria, even if it makes 30 percent from the sale of Juul products, still makes 100 percent from the sale of its own products.

Further, it could now serve Altria’s interest if consumers buy both, so-called “dual-use” of cigarettes and e-cigarettes, which is a habit that public health officials loathe because it does little to diminish the threat of cancer among users.

Barnaby Page, editorial director of ECigIntelligence.com, sees the acquisition as indicative of Altria’s future direction. “For Altria, I think we have to see it as part of a larger strategy including the cannabis and beer investments,” Mr. Page said. “Possibly looking forward to a post-Marlboro future in which it is a more wide-ranging sin industry operator, rather than simply a tobacco company.”