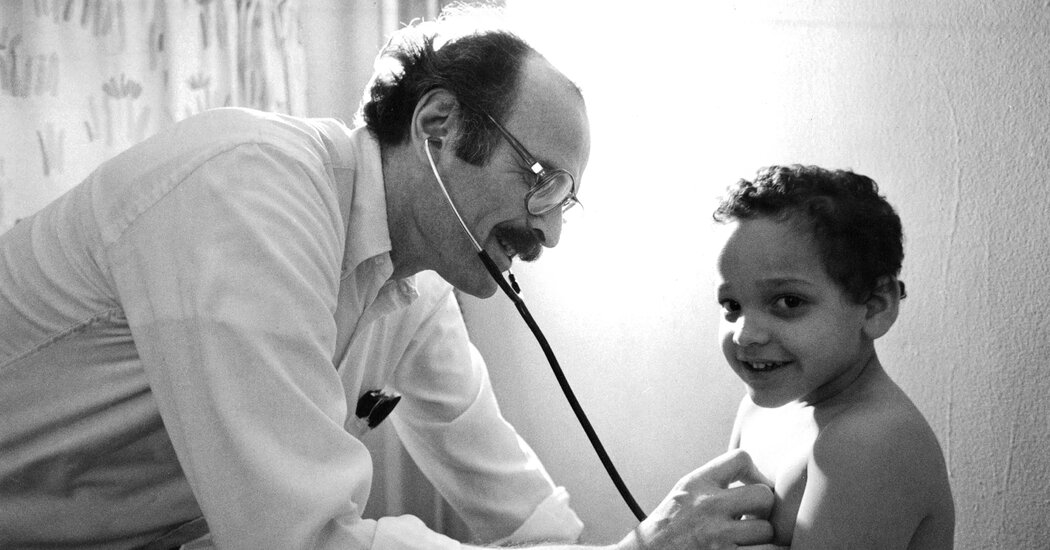

Nicknames captured his intensity and good will. To a fellow doctor, he was “the Last Angry Man”; to a longtime patient, he was “the Guardian Angel of Avenue D”; and to the cartoonist Stan Mack, who depicted Dr. Kramer several times in Real Life Funnies, his weekly comic column for The Village Voice, he was “Dr. Quixote.”

Joseph Isaac Kramer was born on Dec. 7, 1924. His parents, Selig and Frieda (Reiner) Kramer, ran Kramer’s Bake Shop in Williamsburg. Joe would pitch in as a cashier — resentfully. Sent out to run the occasional errand, he took breaks to do what he really wanted — play stickball.

He earned a diploma at Boys High School in Brooklyn, graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1949 from the University of Kentucky, then left for Europe to find an affordable medical school that would accept Jews. He graduated from the University of Mainz, in Germany, around 1960. In 1963, he married Joan Glassman shortly after they had been introduced by friends.

Dr. Kramer’s Lower East Side practice lacked a nurse, leaving him to devote hours each day, and every weekend, to filling out forms. In one instance, he requested $19 from Medicaid after spending 10 hours helping a suicidal young patient and got only $11. Continually enraged by what he saw as the stinginess and inaccessibility of the American medical system, he developed severe hypertension.

He quit the practice in 1996, occasioning a final wave of attention from the news media. “It wasn’t the rise of AIDS, the spread of TB, the resurgence of measles,” The Associated Press wrote in explaining his departure. “It wasn’t his 71 years, and it wasn’t the money. It was the paperwork.”

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by his wife; a son, Adam; and two grandchildren.

Every August, Dr. Kramer attended a reunion of Lower East Side old-timers at East River Park. In a phone interview, Tamara Smith, a patient of his when she was a little girl, recalled hundreds of people swarming around Dr. Kramer as he entered the park for one such gathering — confirmation of his legacy as a “country doctor” who had treated generations of families.

“He couldn’t even get off the ramp to get into the park,” Ms. Smith said. “He was every child in the ’hood’s doctor. I don’t know how he managed that, but he saw every one of us.”