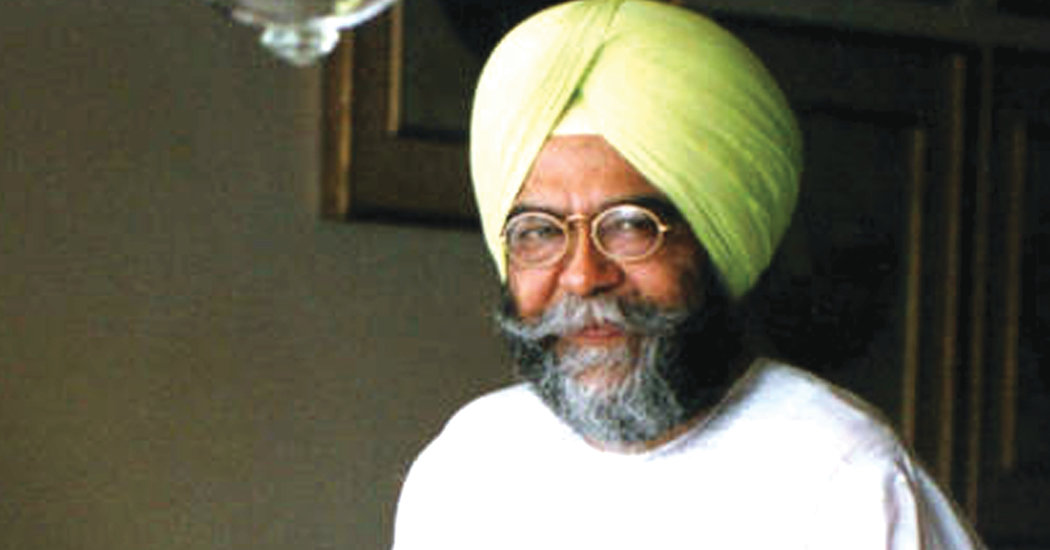

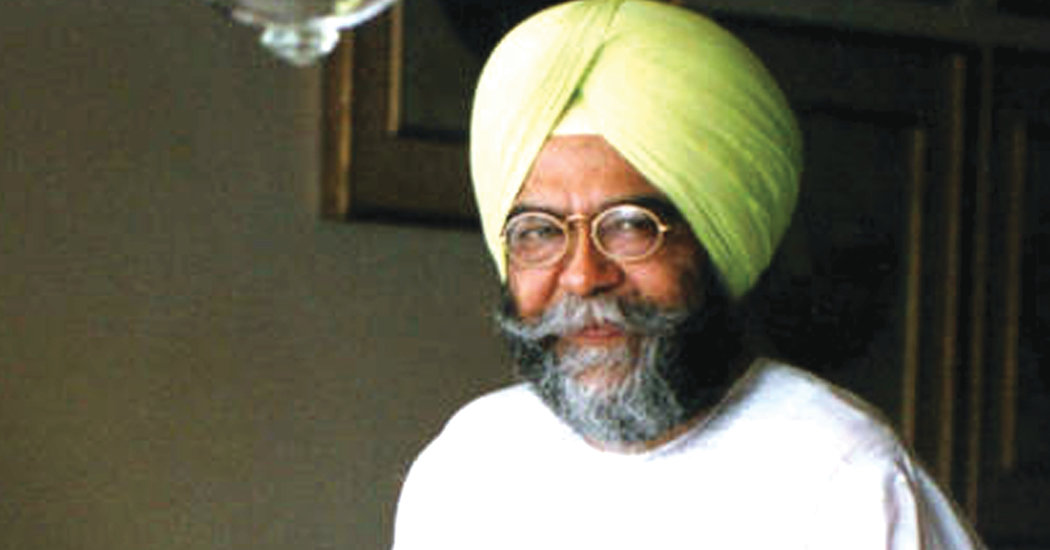

Jiggs Kalra, a food writer who helped elevate Indian fine dining, and a gastronome who threw the spotlight on little known chefs, making their recipes accessible to generations of home cooks, died on Tuesday at a hospital in New Delhi. He was 72.

His death was announced by his son Zorawar Kalra, a leading Indian restaurateur, who said the cause was heart failure. He said his father had been ailing for some time and had used a wheelchair after a stroke several years ago.

Through his newspaper columns and cookbooks, Mr. Kalra sought to preserve and promote local culinary traditions at a time when Indian food was not considered haute cuisine. In India, eating out often meant going either to restaurants at five-star hotels or to fast food outlets. Regional dishes and ingredients were not seen on menus in big cities.

Mr. Kalra wrote about innovative restaurants, unusual ingredients and new and old techniques in Indian cuisine. He was “one of the pioneers of the Indian food movement,” Floyd Cardoz, a New York City-based chef from Mumbai, wrote on Twitter.

With his encyclopedic knowledge of North Indian cuisine, Mr. Kalra was often the last word on authenticity; he was frequently sought out by restaurants and hotels to perfect recipes and develop menus.

His efforts in particular to chronicle and promote Awadhi cuisine, based in the royal city of Lucknow, with its delicate pulaos, savory kebabs and emphasis on slow cooking (known as “dum pukht”), is said to have changed Indian restaurant menus across the world.

His extensive research and travels yielded several collections of recipes, including “Prashad: Cooking With Indian Masters” (1986), which profiles top chefs like Manjit Gill and Arvind Sarawast and incorporates dishes from across India. Many refer to it as the bible of Indian cooking.

For home cooks, “Prashad” pulled back the curtain on restaurant staples, showing how to use a base of sauces and pastes to assemble any dish quickly. It went beyond classic dishes to showcase innovations like Tandoori lobster and shrimp salad.

Though commonly mistaken for a chef, Mr. Kalra never claimed to be one. He had no formal culinary training; rather, his love of food began in a very traditional way — with his mother’s cooking.

Jaspal Inder Singh Kalra was born on May 21, 1947, in the Punjab region to Pritpal and Joginder Singh Kalra, a brigadier in the Indian Army. In addition to his son, Mr. Kalra is survived by his wife, Lovjeet; another son, Ajit; and four grandchildren.

Mr. Kalra attended Mayo College, an elite boarding school in Rajasthan, where he was captain of the basketball team (and where he may have acquired the nickname Jiggs). Soon after graduating, he started working as a trainee journalist at The Times of India in Bombay.

His friend, Bikram Vohra, described a chaotic bachelor life: big parties with good food, lots of alcohol and notable guests, including Bollywood stars and a neighbor who would become the frontman for the rock group Queen, Farrokh Bulsara, better known as Freddie Mercury.

Mr. Kalra went on to cover the 1971 India-Pakistan war for a sister publication, The Illustrated Weekly of India, working under its iconoclastic editor, Khushwant Singh, while pestering him to commission a food column. It was Mr. Singh who later called him “the tastemaker to the nation.”

Mr. Kalra moved to The Evening News in New Delhi and got his food column, “Platter Chatter,” reviewing restaurants and culinary trends in the capital. It was one of the few such columns in India at the time, and he viewed his role as to appraise restaurants, not criticize them; his son Zorawar said Mr. Kalra did not want to hurt any restaurant’s business.

In the 1980s, Mr. Kalra was host of one of India’s first television cooking shows, the popular “Daawat” (“Banquet”), in which he brought on chefs to cook their signature recipes on camera and share their techniques.

Mr. Kalra delighted in putting little known chefs in the spotlight.

When the ITC Maurya luxury hotel invited him to help its flagging restaurant, he persuaded the management to take its chef, Imtiaz Qureshi, out of the kitchen and make him the face of the enterprise in its marketing. He also had the management change the restaurant’s name to Dum Pukht, to highlight the Awadhi slow-cooking tradition in which the chef had trained.

“Other hotels followed suit” by putting chefs front and center, Vir Sanghvi, a journalist and longtime friend of Mr. Kalra’s, said in a telephone interview. “He did more for Indian chefs than any other person.”

Mr. Kalra organized culinary festivals at hotels in New Delhi, bringing in street food and small-town cooks and introducing new fare to suburban Indians. “He could find a kebab guy on a street in Lucknow and get the Oberoi hotel to host him,” Mr. Sanghvi said, referring to one of New Delhi’s most exclusive hotels.

Mr. Kalra had remained active despite his declining health. He was working with his son on a new book compiling hundreds of recipes based on rice, and the two developed the menus and themes for a restaurant line that bears his name: Masala Library by Jiggs Kalra. It has branches in Dubai, Mumbai and New Delhi and serves what Mr. Kalra described in a New York Times review in 2014 as “Indian cuisine version 2.0,” traditional fare with a modern twist.