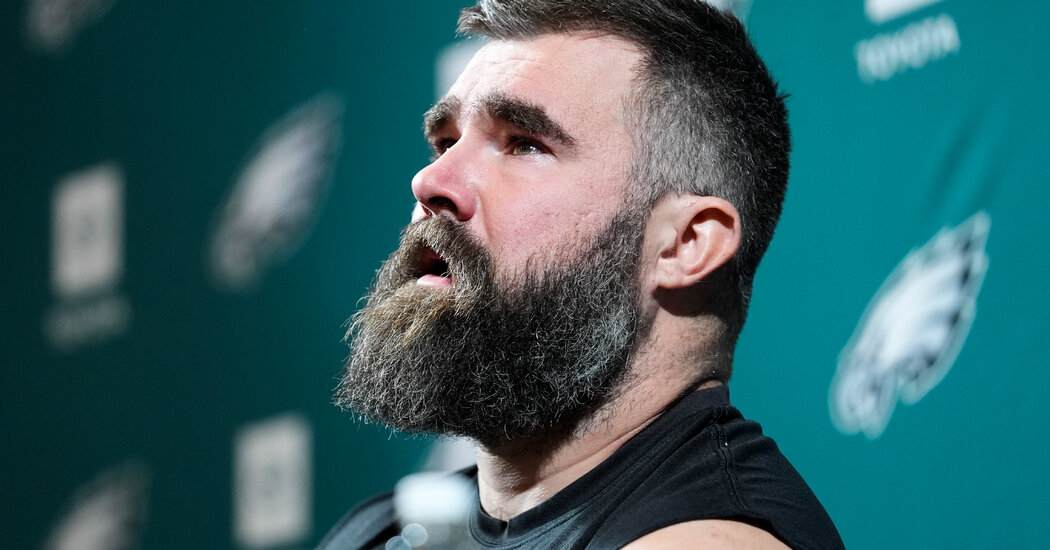

As Jason Kelce strode to a dais on Monday to announce his retirement from the N.F.L. after 13 seasons with the Philadelphia Eagles, he appeared to be playing the role of traditional masculinity to perfection.

His face framed by his familiar Bunyan-esque beard, Mr. Kelce wore a cutoff T-shirt, sandals and a gold Rolex. Taking a seat behind a microphone, he thanked everyone for coming. And then he began to cry.

“Oh, man,” he said through tears. “This is going to be long.”

Sure enough, over the next 40 minutes, Mr. Kelce labored with his emotions as he choked out lines from his speech.

Mr. Kelce cried when he talked about his teammates. He cried when he thanked the Eagles’ owner. He cried when he reflected on the smell of “freshly mowed grass.” He even cried when he recalled instances of other people crying — namely, his father, who, according to Mr. Kelce, had “tears streaming down his face” when Mr. Kelce was drafted in 2011.

But it was only when Mr. Kelce spoke about his relationship with his younger brother, Travis, a tight end for the Kansas City Chiefs, that Jason seemed in danger of having a total meltdown. Travis, of course, was sobbing behind sunglasses in the front row. Someone tossed a towel to Jason so he could mop his face.

“This is where it’s going to go off the rails,” he said.

If not exactly taboo, crying in men’s sports was once considered a sign of weakness. Think Jimmy Dugan, the irascible manager from the film “A League of Their Own,” chastising a woman playing for him by bellowing, “There’s no crying in baseball!” Men like Dugan, both real and fictional, were always free to express anger, because anger was masculine. But tears? Those had no place on a ball field.