Dr. James S. Ketchum, an Army psychiatrist who in the 1960s conducted experiments with LSD and other powerful hallucinogens using volunteer soldiers as test subjects in secret research on chemical agents that might incapacitate the minds of battlefield adversaries, died on May 27 at his home in Peoria, Ariz. He was 87.

His wife, Judy Ketchum, confirmed the death on Monday, adding that the cause had not been determined.

Decades before a convention eventually signed by more than 190 nations outlawed chemical weapons, Dr. Ketchum argued that recreational drugs favored by the counterculture could be used humanely to befuddle small units of enemy troops, and that a psychedelic “cloud of confusion” could stupefy whole battlefield regiments more ethically than the lethal explosions and flying steel of conventional weapons.

For nearly a decade he spearheaded these studies at Edgewood Arsenal, a secluded Army chemical weapons center on Chesapeake Bay near Baltimore, where thousands of soldiers were drugged.

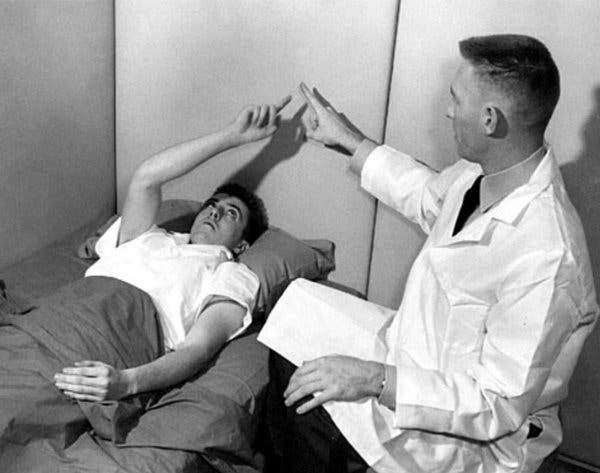

Some could be found mumbling as they pondered nonexistent objects, or picking obsessively at bedclothes, or walking about in dreamlike deliriums. Asked to perform reasoning tests, some subjects could not stop laughing.

It sometimes took days for the effects to wear off, and even then, Dr. Ketchum wrote in a self-published memoir, many displayed irrational aggressions and fears. He built padded rooms to minimize injuries, but occasionally one would escape. Some soldiers smashed furniture or menaced others, imagining they were running from hordes of rats or killers.

“The idea of chemical weapons is still preferable to me, depending on how they are used, as a way of neutralizing an enemy,” Dr. Ketchum told The New York Times in an interview for this obituary in 2016, a half-century after his groundbreaking experiments. “They are still more humane than conventional weapons currently being used, if the public can ever get over its psychological block of being afraid of chemical weapons.”

In 2006, in a self-published memoir, Dr. Ketchum described the effects of LSD and other drugs used in experiments with soldiers who had volunteered for the project.

A Cornell Medical School graduate who joined the Army and served his internship and residency at military hospitals in the 1950s, Dr. Ketchum had become a passionate believer in nonlethal chemical warfare by the time he finished his medical training, and in 1961 he jumped at the chance to join the Medical Research Volunteer Program at Edgewood Arsenal, a facility built during World War I, when chlorine and mustard gas had devastated troops.

The research program there, a Cold War project, had no connection with the notorious mind-control experiments conducted by the C.I.A. in the 1950s, in which LSD was tested on unwitting civilians.

Starting as an ordinary researcher, Dr. Ketchum moved up to chief of psychopharmacology, head of clinical research and then chief of behavioral sciences, designing and orchestrating all program research.

Army investigators said that some 5,000 soldiers were tested with drugs during Dr. Ketchum’s tenure at Edgewood, and that no one had died or been seriously injured in his experiments. The Army ended drug testing at the site in the 1970s, concluding that using chemical agents to incapacitate enemy forces, especially on a large scale, was impractical.

In his memoir, “Chemical Warfare Secrets Almost Forgotten: A Personal Story of Medical Testing of Army Volunteers” (2006), Dr. Ketchum said he had embraced the program in hopes of developing mind-altering chemical weapons that might save lives and limit maiming on the battlefield.

“I was working on a noble cause,” he wrote. “The purpose of this research was to find something that would be an alternative to bombs and bullets.”

Critics said that his test subjects had been induced to volunteer with offers of extra pay, weekend passes and light duties, and that they had been misled by legalistic waivers, signed for each experiment, that minimized the risks and the consequences of the drugs they were given. But Dr. Ketchum insisted that his subjects — screened to eliminate drug abusers and criminals — were fully informed about test methods and the probable effects of the drugs, which were identified only by code names.

“We were in a very tense confrontation with the Soviet Union,” The New Yorker magazine, in a 2012 profile of Dr. Ketchum, quoted him as having once told a radio audience, “and there was information that was sometimes accurate, sometimes inaccurate, that they were procuring large amounts of LSD, possibly for use in a military situation.”

Dr. Ketchum with a subject of his Army drug experiments in the 1960s. “The idea of chemical weapons is still preferable to me, depending on how they are used, as a way of neutralizing an enemy,” he said in 2016.Creditvia Judy Ketchum

While the experiments used popular recreational drugs of the 1960s counterculture — marijuana derivatives, mescaline and lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD — many subjects were exposed to a more powerful compound called BZ (3-quinuclidinyl benzilate), which produced acute anxiety, paranoia and delusions.

To test soldiers’ performance under the influence of BZ, Dr. Ketchum in 1962 had a fully equipped communications outpost constructed at Edgewood — an enclosed mock-up resembling a Hollywood set. One soldier received a placebo, but three others were given varying doses of the drug. All were locked up in the “communications center” and for three days subjected to barrages of commands and messages suggesting that they were under attack.

Dr. Ketchum, who often filmed his experiments with a theatrical flair, called this scenario “The Longest Weekend.” As hidden color cameras rolled and radio warnings of chemical assaults intensified, soldiers panicked, donned gas masks, tried to escape and lapsed into deliriums that lasted up to 60 hours. The Army concluded that BZ could disable a small military unit in a compact space, and for a time produced stockpiles of volleyball-size BZ bomblets.

But to test BZ in battlefield conditions, Dr. Ketchum in 1964 developed a sprawling experiment, code-named Project Dork, at the Army’s Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, to determine if clouds of BZ could incapacitate enemy troops at 500 and 1,000 yards. He deployed soldiers in goggled masks and protective clothing, two prefabricated hospitals staffed with doctors and nurses, a generator to create BZ clouds, and television cameras to make a documentary.

He called this 45-minute black-and-white film “Cloud of Confusion.” With Bela Bartok’s “The Miraculous Mandarin” as mood music, a white cloud engulfs soldiers as a narrator intones, “And on this desert this cloud was unleashed so men could measure the dimensions of its stupefying power.”

The soldiers are seen disoriented, stumbling about in confusion. But Army officials ruled the test a failure because there was no way to control the psychedelic cloud.

On leave from Edgewood from 1966 to 1968, Dr. Ketchum studied at Stanford University, made documentaries of San Francisco’s psychedelic subculture, and treated drug-overdose victims at a clinic in the Haight-Ashbury section of the city.

He continued experiments even after the Army had rejected using hallucinogenic agents as weapons in the Vietnam War. He left Edgewood in 1971, served at Army posts in Texas and Georgia and resigned his colonel’s commission in 1976 to return to civilian psychiatry.

Edgewood Arsenal today is a collection of derelict buildings attached to a military proving ground, its records housed in the National Archives.

James Sanford Ketchum was born on Nov. 1. 1931, in Manhattan, the older of two sons of Milton and Cecilia (Matson) Ketchum. He grew up in Brooklyn and the Forest Hills neighborhood of Queens. His mother was a secretary, and his father was a telephone company manager and a deacon of the Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan, whose pastor, Norman Vincent Peale, wrote “The Power of Positive Thinking.” James and his brother, Robert, attended public schools in Queens.

After graduating from Forest Hills High School in 1948, James attended Dartmouth College. He later transferred to Columbia University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1952. He received his medical degree from Cornell in 1956, joined the Army and served an internship at Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco and a residency at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington.

Dr. Ketchum was married five times. His marriage in 1951 to Joan O’Leary ended in divorce in 1953. His marriage in 1959 to Doris Fautheree was annulled in 1967. His third marriage, to Phyllis Pennington, in 1968, ended in divorce in 1973. He married Margot Turnbull in 1973, and that marriage, too, ended in divorce, in 1986. He married Judy Ann Schaller in 1995.

In addition to his wife, his survivors include a son, Kevin, from his second marriage; a daughter, Robin Ketchum, from his fourth marriage; a brother, Robert; and a grandson. A daughter from his second marriage, Laura, died in 2017.

After returning to civilian life, Dr. Ketchum taught medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles; worked in hospitals and clinics; and treated alcohol and drug abuse cases in private practice until retiring in 2001. He wrote many treatises on pharmacology and other subjects.

His wife said he was to be given a military burial at National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona in Phoenix.

In The New Yorker profile, Dr. Ketchum was asked if he had continued to wrestle with the ethical dimensions of his experiments on soldiers in the 1960s — whether he had placed the interests of the nation, as he saw them, above those of individuals.

“I struggle with these things,” he said. But, he added, “I have always had the feeling that I am doing more the right thing than the wrong thing here.”