The life-changing experience for James A. Duke came as he roamed the lush jungles of Panama in the mid-1960s, munching on the plants indigenous peoples used for food and medicine and learning firsthand about them.

At the time, he was two years into his job as a botanist for the Department of Agriculture and working on a federal project, ultimately abandoned, to determine the feasibility of excavating an alternative to the Panama Canal using low-level nuclear bombs.

And what he found there, and ate, excited his imagination and led him to embrace ethnobotany, a then-emerging field that investigates the healing properties of plants that indigenous peoples have used for millenniums.

His field work, incorporating botany, natural healing and anthropology, took him to remote corners of the world, often in the company of native guides and even shamans — worlds away from his early professional success as a standup-bass player in country, bluegrass and jazz bands.

His peripatetic research made him a widely acknowledged expert at a time, the 1960s, when interest in traditional cultures was on the rise, in tandem with the burgeoning counterculture in Western countries.

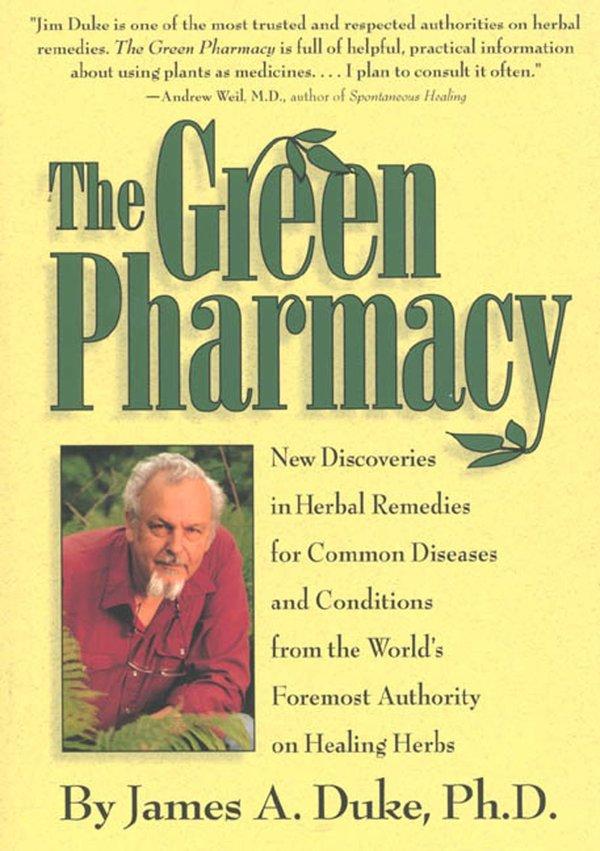

Dr. Duke was also a pioneer in identifying phytochemicals, the now familiar, often beneficial chemical constituents of foods like antioxidants in oregano and flavonoids in green tea. He poured the results of his work into a 1997 book, “The Green Pharmacy: New Discoveries in Herbal Remedies for Common Diseases and Conditions From the World’s Foremost Authority on Healing Herbs,” as well as into an extensive database he compiled for the Agriculture Department.

The book has sold more than 1.5 million copies, according to the publisher, Rodale Press.

For all Dr. Duke’s achievements, however, his death, on Dec. 10, 2017, at 88, did not draw widespread attention; it was reported at the time mainly by organizations devoted to botany or nutrition. The New York Times learned of his death recently while seeking to update this obituary, which was written about four months before his death.

His daughter, Celia Gayle Duke Larsen, said Dr. Duke died at his home on his six-acre herb farm in Fulton, Md. No specific cause was given. In addition to Ms. Larsen, he is survived by his wife, Peggy-Ann K. Duke; a son, John; four grandchildren; and one step-grandchild.

In “The Green Pharmacy,” Dr. Duke wrote that the trip to Panama, his second, involved interviewing local people about the wild plants they ate. The aim was to determine how long they might be displaced from their homes and way of life — “six days, six months, six years, six centuries or six millennia,” he wryly wrote — if the local flora were destroyed in building an alternative canal.

The local people, Choco and Kuna Indians, knew exactly what was going on, Dr. Duke wrote, and sometimes asked if similar nuclear-based efforts were being used in, say, dredging the Great Lakes. The effort, sponsored by the now-defunct Atomic Energy Commission, sputtered and was allowed to lapse.

“The Green Pharmacy” took a folksy, anecdotal, sometimes whimsical approach to describing the herbs, foods and teas that Dr. Duke recommended for various ailments, arranged alphabetically. He named one tea “DyspepsiKola.”

A gentle exhortation often followed a recommendation. After noting that the herb chamomile, which is known to soothe nerves, also has potent anti-inflammatory compounds, he wrote, “If I had carpal tunnel syndrome, I’d drink several cups of chamomile tea a day.”

Dr. Duke stressed that the stories he had heard, whether from indigenous peoples or the doctors and other herbalists cited in the book, often reflected empirical and historical findings about healing plants.

He was critical of pharmaceutical companies and the doctors who zealously prescribed their products. Skeptical of the high prices and side effects of modern drugs, he championed plant medicines as a viable alternative.

“If you and I go around sucking on licorice root, which can guard against ulcers, that’s not going to make any money” for drug companies, he told Anne Raver, a gardening columnist for The Times, in 1991.

Dr. Duke had his own remedies. “To cure a cold, he mashes up the stems and leaves of forsythia,” Ms. Raver wrote. “To help strengthen weak capillaries, he makes ‘rutinade’ from violet and buckwheat flowers, lemongrass and rhubarb stalks, and herbs high in rutin (anise, chamomile, mint, rose hips).”

Dr. Duke’s authoritative reference book from 1997 has sold more than 1.5 million copies, according to its publisher, Rodale Press.

He also made lemonade from the wild plant Mayapple and wrote a ditty about it:

Penobscot Indians up in Maine

Had a very pithy sayin’:

Rub the root on every day

And it will take your warts away!

. . . I’ll venture to prognosticate

Before my song is sung:

This herb will help eradicate

Cancer of the lung.

James Alan Duke was born on April 4, 1929, in Eastlake, a suburb of Birmingham, Ala., to Robert Edwin and Martha (Truss) Duke. His love of plants, he wrote, came from his mother, an avid gardener, and from spending time in the woods of rural Alabama with “country cousins” and an elderly neighbor, who introduced him to edible wild plants, like chestnuts and watercress.

His parallel love of music began when he was 5 years old: He was selling magazines to help earn money for his family when he encountered bluegrass musicians in a local college dormitory.

After the family moved to North Carolina, he learned to play the bass fiddle in high school and began performing with Homer Briarhopper and His Dixie Dudes, a country band he had heard on the radio. At 16, he played on a 78-r.p.m. record that the band cut in Nashville.

Dr. Duke attended the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where his bass playing caught the ear of Johnny Satterfield, a big-band leader who taught there. He recruited Jim Duke as a jazz bassist, on the condition that he enroll in the music program.

His native love of botany kicked in, though, and from 1952 to 1960 he earned bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in botany at Chapel Hill. He did postdoctoral work as a professor at Washington University in St. Louis and curatorial work at the Missouri Botanical Gardens there.

Botany and music continued to be entwined in his life, however. While working, he would pick up gigs at clubs and perform with jazz, blues and country singers.

“The deeper I delved into botanical medicine with its earthy folk roots,” Dr. Duke wrote, “the more comfortable it ‘fit’ with the music I played, which also had deep roots in the same earthy folk experience.”

He married Peggy-Ann Wetmore Kessler, a fellow botanist, in 1960. An illustrator as well, she made all the drawings for “The Green Pharmacy.”

Dr. Duke’s first work experience in Panama involved identifying plants along the last uncompleted stretch of what would become the Inter-American Highway, reaching from Alaska to Chile. His team collected more than 15,000 specimens in the two and a half years he spent on that trip to Panama.

Dr. Duke held various positions at the Agriculture Department. As chief of the Plant Taxonomy Laboratory, he traveled to South America to help the State Department investigate and limit the cultivation of coca, from which cocaine can be extracted. He also visited Vietnam and neighboring Southeastern Asian countries to identify cash crops that might be grown as alternatives to the widely cultivated opium poppy.

He got what he called his “dream job” at the department in 1977, as head of the Medicinal Plant Laboratory. In that job he traveled to China, the Middle East and South America to collect specimens for a cancer-screening program being run jointly with the National Cancer Institute. The program, he wrote, analyzed 10 percent of the world’s known plant species for anti-tumor activity.

After retiring from the Agriculture Department, Dr. Duke sometimes conducted tours, often barefoot, along the Amazon River in Peru. He’d also give tours of his herb farm, the Green Farmacy Garden, in Fulton, about 18 miles north of Washington.

Dr. Duke’s other books include “Handbook of Medicinal Herbs,” an authoritative reference work first published in the late 1980s, and “The Peterson Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America,” which he wrote with the herbalist Steven Foster.

In 1991, Herbert Pierson, a fellow Cancer Institute toxicologist, told The Times that Dr. Duke’s strength as an expert in herbal remedies was in his own firsthand experimentation, measuring the effects of plants on himself.

“He actually practices what he preaches,” Dr. Pierson said. “Nobody should underestimate his knowledge. He knows from folkloric use that these things aren’t used by chance, that they’ve survived the test of time.”

Indeed, in an interview with Ms. Raver in 1992, Dr. Duke spoke about his enthusiasm for dandelion. He liked the roots pickled in old pickle vinegar, and he had eaten every part of the dandelion, from root to seed.

“Dandelions are extremely rich in beta carotene and ascorbic acid, the flowers in particular,” he said. “I sometimes eat 100 flowers in a day. I was trying to see if I’d turn orange from beta carotene, and it didn’t work.”