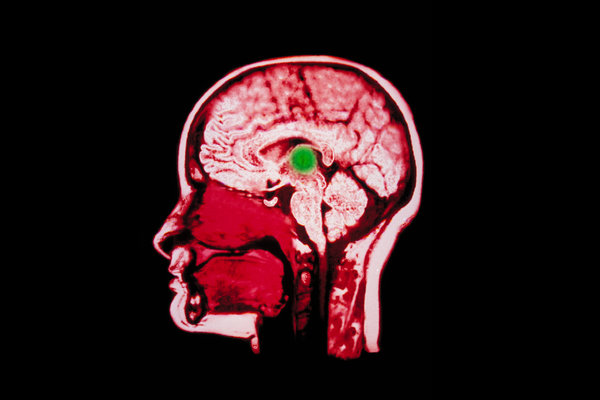

Doctors have known for years that some patients who become unresponsive after a severe brain injury nonetheless retain a “covert consciousness,” a degree of cognitive function that is important to recovery but is not detectable by standard bedside exams. As a result, a profound uncertainty often haunts the wrenching decisions that families must make when an unresponsive loved one needs life support, an uncertainty that also amplifies national debates over how to determine when a patient in this condition can be declared beyond help.

Now, scientists report the first large-scale demonstration of an approach that can identify this hidden brain function right after injury, using specialized computer analysis of routine EEG recordings from the skull. The new study, published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that 15 percent of otherwise unresponsive patients in one intensive care unit had covert brain activity in the days after injury. Moreover, these patients were nearly four times more likely to achieve partial independence over the next year with rehabilitation, compared to patients with no activity.

The EEG approach will not be widely available for some time, due in part to the technical expertise required, which most I.C.U.’s don’t yet have. And doctors said the test would not likely resolve the kind of high-profile cases that have taken on religious and political dimensions, like that of Terri Schiavo, the Florida woman whose condition touched off an ethical debate in the mid-2000s, or Karen Ann Quinlan, a New Jersey woman whose case stirred similar sentiments in the 1970s. Those debates centered less on recovery than on the definition of life and the right to die; the new analysis presumes some resting level of EEG, and that signal in both women was virtually flat.

But the EEG approach, once tested more broadly and refined, will likely change standard practice, some experts said, helping guide treatment decisions in the excruciating first days and weeks after a brain injury.

“This is very big for the field,” said Dr. Nicholas Schiff, a professor of neurology and neuroscience at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. “The understanding that, as the brain recovers, one in seven people could be conscious and aware, very much aware, of what’s being said about them, and that this applies every day, in every I.C.U. — it’s gigantic.” The finding, he added, “should change practice requirements around the world.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Other doctors said it was still too early to predict the impact of the new technique. “This approach is not ready to be incorporated into standard practice at this time, as we are just not able to reliably predict outcomes early after injury,” said Dr. Flora Hammond, chair of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Indiana University School of Medicine.

In the new analysis, researchers at Columbia University and New York University tracked 104 unresponsive patients in Columbia’s neurological I.C.U., taking EEG recordings from each in the first few days after injury. The brain injuries had a variety of causes, including blows to the head, heart attack and internal bleeding. During each EEG recording, the researchers gave the patients instructions through headphones, including, “Begin opening and closing your right hand,” and “Stop opening and closing your right hand.”

The researchers fed the EEG data into a machine-learning algorithm, which compared the brain activity following each command to resting-state activity, looking for distinct and consistent differences — the chatter of motor signals, filtered from the background noise. And in 16 patients, hidden activity became evident. Previous research, in patients who had been unresponsive for years, had found that a subset showed hidden brain function. The new study is the first to use this approach to examine a large number of patients just after the injury.

“Somewhat to our surprise, we found that about 15 percent of patients who were not responding at all had this brain activation in response to the commands,” said Dr. Jan Claassen, medical director of the neurological I.C.U. at Columbia and the lead author of the paper. “It suggests that there’s some remnant of consciousness there. However, we don’t know if the patients really understood what we were saying. We only know the brain reacted.”

The researchers tracked the progress of all of the patients for a year following injury. Patients in both groups showed real improvement, but those with the hidden brain activation had a better prognosis overall, the study found. After a year, seven of the 16 patients with covert activity had recovered to the point where they could function without help for at least eight hours. By contrast, 12 of the other 88 had reached that level of recovery.

The research team will need to study more patients, for longer, to better understand the relationship of EEG activity to eventual outcome and to the underlying biology of the injury, Dr. Claassen said.

But for now, many neurologists believe that the field is on the verge of gaining useful insight into the mute, immobile but very human patients in their care. “This approach is not perfect; there are false-negative results, and false-positive ones,” said Dr. Brian Edlow, associate director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Neurotechnology and Neurorecovery. “But this study suggests that there are compelling reasons to acquire these types of data. And it’s not hard to imagine a future where I.C.U.’s routinely get these data and send them off for analysis.”