A paradise for skiers, the Italian Alps of South Tyrol offer a more placid pastime that’s surging anew. A host of spas are sprouting up in isolated tracts among the highlands, and though there’s hiking, biking and access to some of the Alps’ easier ski slopes, sports are a mere afterthought here. The spas draw skiers and nonskiers alike to spend days soaking in hot tubs, besotted by the view of these commanding, ice-shrouded peaks.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, when mineral springs became Europe’s cure-all for medical ills, wellness seekers flocked to the region’s famous waters and sanitariums. Today’s alpine spas are updating this long tradition as the present-day search for wellness has reinvigorated the desire for their timeless sedative effects.

For those of us who have forgotten what a multitude of stars looks like, the Italian Alps offer an immersion into lost wonders of contemporary life. Untrammeled snow. Unsullied air. A velvet cloak of silence. And the immeasurable reprieve of poor cellphone receptions.

It’s little surprise that these mountains have become the locus of a cluster of modern spa destinations designed to draw city dwellers to a place where tranquillity imposes itself by the very nature of the landscape.

The San Luis Retreat Hotel & Lodges near Merano opened in 2015. The San Luis has individual cabins of one or two floors.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

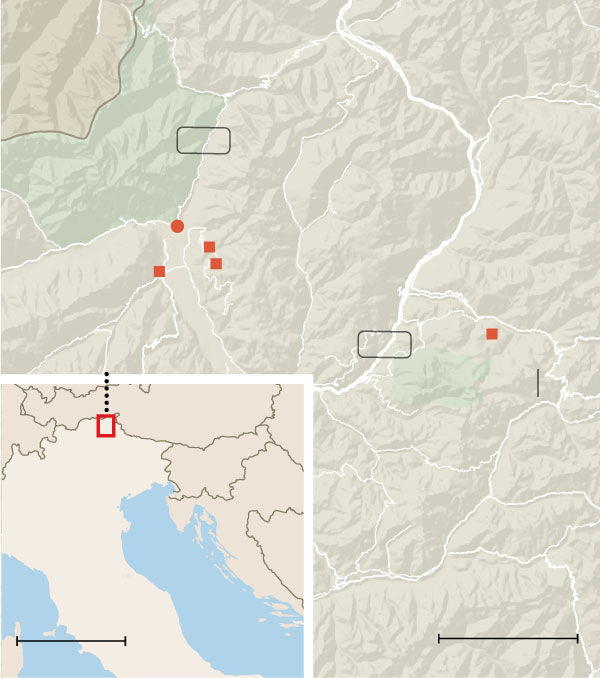

In December, I headed to the Alps to see how these age-old cures stood up to our high-intensity era of stress and self-care, visiting four contemporary spas set amid the summits of Italy’s South Tyrol region.

These spa hotels are dramatically modern, with bold architecture and cutting-edge restaurants. Their pools, saunas and hot tubs are designed for a forward-looking aesthetic and include outdoor heated pools that allow visitors to enjoy the mountain views alfresco, even when surrounded by snow. Though the look is up-to-date, the cures — hot soaks, massages, mountain air — are classic, and beckon a new generation in search of health and relaxation.

In their heyday, spas were metropolitan affairs, situated in cities like Merano. Health-seekers flocked to them for their restorative waters and for the society they provided at the theaters, casinos and dance halls that were common resort amenities.

In ancient times, the bathhouses that the Romans adapted from the Greek tradition were even more integral to cosmopolitan life. There were 952 bathhouses in Rome by 354 A.D.; they often included libraries, gyms, lecture halls, medical treatment facilities and gardens. The Baths of Diocletian alone accommodated up to 3,000 visitors at a time.

Today bathhouses are rare on our city maps, and serenity is a luxury reserved for infrequent vacations. Spas now must be deep in the woods, the dislocation and the staggering view of the mountains the only way to finally subdue us.

Modern Alpine spa resorts reimagine the mountains’ traditional wooden huts as lofty architectural temples of repose. On the sprawling plateau of the Alpe di Siusi in the Dolomites, set upon a grassland slope dotted with diminutive log cabins, the Adler Mountain Lodge mirrors the rustic little dwellings of its neighbors, but in palatial form. Built in the raw timber of local spruce trees, the double-gabled main hotel and a dozen surrounding chalets for rent are fronted by full glass walls, offering an awe-inspiring gaze at the serrated monoliths of the Sassopiatto and Sassolungo mountains, which rise like spiky arrowheads to lance the sky.

To pull back the morning curtains on this jagged expanse — the rocky massifs jangling in the bright sun or softened by fields of fresh falling snow — is to wake up to the grandeur of the greater world that, in our insular daily lives, we so easily forget.

Of course, the mountain views are just the beginning. There is a spa. A saltwater, womb-warm pool, constructed of the local silvery quartzite rock and filled by a nearby spring, extends from inside to out, where steam rises off the surface into the chilly air as visitors bob and recline, enveloped in Jacuzzi bubbles as they contemplate the horizon’s mammoth stony outcroppings. Two pinewood saunas, one filled with Tyrolean hay and its sharp, dry-earth perfume, offer panoramic views of the rough-chiseled topography. In the saunas — as in all the saunas of this area — genders are mingled and nude or lightly wrapped in towels. But as long as you’re comfortable glimpsing bare bodies, the personal sensation of simmering your own swimsuit-free body is, frankly, worth it.

Adler’s spa offers a post-excursion massage using Alpine arnica extract and mud to soothe overexerted legs, but no one seems to be in a great stink to get sporty here. There are options, though: The area offers a paradise for hikers, electric bikes are available in the summer and you can ski right out of the locker-room door onto mountain paths in the winter. The trails are wide and easy, and guests generally hit the slopes for a couple of hours at most. “Our slopes are good for cruising and enjoying the view,” says Nicol Lobis, a staff member at Adler Mountain Lodge. “But people come here to relax, not to burn their thighs to the max on black diamond slopes.” And besides, the bar is open all day.

For all its healthy overtones, Adler is an all-inclusive resort, serving up plentiful, thrice-daily meals and snacks in between. An all-hours bread and cheese buffet, like the well-stocked bar, is self-serve, giving the stay a decidedly more indulgent slant.

The restaurant’s dishes reflect South Tyrol’s unique history. A territory of Austria until World War I, the region’s primary language is still German; and smoked fish, caraway seeds, horseradish, beets and the very distinctive taste of milk thistle oil mark its cuisine as more Central European than Mediterranean, despite belonging to Italy for the last century. Yet the Adler dedicates Italian-style special attention to superbly high-quality local ingredients.

The hotel opened in 2014 and was the first resort of its kind in this Arcadian area of the Alpe di Siusi, which, as part of the Unesco-protected Dolomites, allows only a handful of cars and even fewer building developments.

In Italy’s Alps, the modern movement of forest spas launched with the opening of the Vigilius Resort in 2003. Designed by the renowned architect Matteo Thun, the hotel is a starkly contemporary expanse of glass and lumber 5,000 feet up the mountainside, reachable only by cable car. In its first years, the Vigilius won awards for its sustainable energy approach and introduced the idea of the eco resort to the area, setting the bar for subsequent spas’ natural material use and extreme energy efficiency. The Vigilius’s glass-fronted sauna and indoor-outdoor heated pool immerse visitors in a dramatically dense view of larch trees and craggy peaks, but the resort is in need of a refresh to keep up with the high style introduced by more recent eco resorts in the vicinity.

Atop the isolated Avelengo plateau visible on a mountaintop opposite the Vigilius, the San Luis Retreat Hotel & Lodges is a collection of modern chalets and “tree houses” on stilts, all splayed on a meadow around a central lake, with hills of larch trees rising behind. There are no rooms at this hotel; instead, there are individual cabins of one or two floors, with rosy exteriors of aged, untreated wood that face the water and the nighttime fire pits along its piers. Their hardwood interiors pair polished modern interpretations of farmhouse furniture with a crackling fireplace, a private hot tub on the deck and a sauna with a panoramic glass wall, so guests can enjoy spa time in solitude — perhaps the most romantic setup of the resorts in South Tyrol.

“Everyone lives in cities, but they all dream of a house in the woods,” said Ilse Meister, who, along with her husband and two grown children, launched the San Luis spa resort in 2015, a countryside complement to the urban Hotel Irma that the family has run in Merano for generations. “We were convinced that in the future, the thing that would be most important for our guests would be total silence.”

As evening falls amid the dimly lit cabins, the only sounds are the occasional bather languidly splashing in the burbling Jacuzzi, and the soft popcorn snaps of newly lit fires, as the last sun rays fade behind the delicate, silhouetted web of pine branches surrounding the ridge. Chimney smoke and the balsamic pitch of evergreen needles scent the clean breeze. At the center of the grounds, a soaring wood-beam lodge — the candle-filled main hall — contains the dining room of the full-board (excluding alcohol) hotel and its main sauna and steam room. A fireplace marks the heart of the glassed-in, gabled-roof barn that holds the heated pool, which opens to an outdoor pool and a Jacuzzi perched on a pier in the middle of the lake, its warm vapors swirling and rising into brisk evening air.

There are no cold-plunge pools here, or seemingly anywhere in South Tyrol — surprising, as the ancient Romans themselves were great practitioners of hot/cold immersion therapy, a practice continued today in many bathing cultures. A frigid shower after the sweat of the sauna will never induce the dazzling, purifying tingle of a full icy dunk: a stupefying feeling that your entire body is mentholated, a trick that keeps you warm through wintry days.

But at the San Luis, you can improvise with a bracing roll in the snow (tried and recommended) or a leap in the lake, depending on the season; and the chalets’ big, free-standing baths can be adapted for cold immersion after partaking of the personal sauna and hot tub (also recommended).

A short car ride away, the Hotel Miramonti is “a mountain hotel in the city,” says Klaus Alber, who opened it in 2016 with his wife, Carmen. It’s distinctly more urban than the other Alpine spa resorts, but its position — secluded on a promontory 4,000 feet above Merano, along a steep country road winding past apple orchards, flocks of grazing mountain goats, a lovely 14th-century Romanesque church and antique castles — is still detached from the hustle and bustle seen vertiginously below.

The red fir lumber exterior of the boutique hotel’s triple-peaked lodge mirrors the mountains across the Merano valley, a majestic palisade of zigzagging, snow-crowned geometry at the sky’s edge that’s visible from each of the hotel’s weathered wood balconies. The rooms — of which the lofts are the coziest — are fitted with raw planks of oak and fir as at the other resorts, but contrasted here with stark white walls and minimalist Scandinavian furniture from Copenhagen’s &Tradition brand; more urban design hotel than chic chalet.

Merano, its illuminated tangle of city streets visible straight down the hotel’s front cliff, is just a 15-minute drive away, and guests often descend for dinner or a day trip. Yet the Miramonti, built on porphyry rock amid a thicket of trees, still has miles of woodland paths just out its back door, and the Merano 2000 ski slopes are a short shuttle ride away.

Set a few steps outside the hotel’s lodge, an elevated pinewood and glass cabin — Miramonti’s forest sauna — allows guests to enjoy Finnish heat while surveying the surrounding copse of firs and the mountain crests in the distance. A hot tub is tucked into nearby bushes. Smart, ash-gray linen recliners line the indoor and outdoor observation deck with a view over the valley. But this slickly modern spa shines brightest with its design-forward, photo-ready outdoor infinity pool, partially covered by a pitched cottage roof and jutting out to seemingly hover above the precipice. Floating at the water’s edge, with the city beneath silenced by its remoteness, the pool’s projection offers a vantage point of quiet calm; the hushed, hulking mountains seem to be all yours.

What does it take to relax these days? As the stresses of work, life and the modern world pile up, perhaps we ought, like Romans, to let our heads float in womb-like bubbles more often.

At the San Luis, I tried a massage, although days of spas had — I thought — already rendered my body the tender consistency of a jellyfish. Yet the masseuse paused as her fingertips alighted on my spine. “Do you spend a lot of time working at a desk?” Well, yes.

She kneaded a constellation of unexpected knots around my shoulder blades, clucking that everyone she saw these days had the same condition. “You need a massage once a week, or you’ll damage your back.” Need, she told me. Need. Did the Romans, with their weekly spa-time and scheduled self-care, have knots in their backs? Perhaps the masseuse is right. Need indeed.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.