Every once in a while a fragrance comes along that causes a rupture in the history of olfaction as we know it, and suddenly it is clear that the scent of the world will never be exactly the same.

Such was the case in October 1994, when CK One had its debut. It was the ultimate anti-1980s, anti-Boomer scent, a riposte to the showy perfumes of the “Dynasty” and Wall Street years, including Calvin Klein’s own best-selling Obsession.

With a bright, citrusy beginning that segued into sweetness and then faded into muskier clarity, it smelled like teen spirit. It was the perfect sensory expression of a generation that grew up at the tail-end of the illusion that was the American dream, without the self-satisfied ambitions of their striving parents, alienated from gold chains, shoulder pads and “Miami Vice” pastels, ambivalent about the concept of … well, pretty much everything.

In its first 10 days, CK One made more than $5 million, according to the company. Twenty bottles were sold every minute. It was available at all 85 Tower Records stores, next to Nirvana albums. (Record stores! Remember them?) Had it been an album, the salespeople said, it would have been the third-best-selling CD of the Christmas season.

In the mid-90s the annual ka-ching count reached approximately $90 million. It “disrupted the fragrance codes of the time,” said Alberto Morillas, the master perfumer who created the scent along with Harry Fremont.

“Everything was a bull’s-eye,” said Mr. Fremont. “Everything was created exactly with this market in mind. And it was a major turning point.”

First, there was the concept itself: the first “unisex” (unisex was the genderless of the ’90s) fragrance, a scent meant for the androgynous slackers that slouched around in one another’s thermals and plaids, that slunk into work in skinny black pantsuits over ribbed tanks and believed in combat boots for all seasons. It was billed as “one for all,” though what that really meant was one for all in this age group, and was greeted as revolutionary. In point of fact, the first perfumes were genderless, and only in the 1930s did the sexes start getting separated. It was then that it occurred to beauty companies that marketing to men might be lucrative. That is to say, CK One wasn’t the first unisex fragrance; it was the first openly marketed unisex fragrance. Which, with its whiff of cynicism, was in itself somehow very Gen X.

That was no accident: According to Mr. Fremont, the original brief came from an extensive study Calvin Klein had conducted on what would appeal to this particular disaffected consumer group.

Then there was the perfume: top notes of bergamot, lemon, mandarin, fresh pineapple, papaya, cardamom, green tree accord; heart notes of florals like violet, rose, lily of the valley; and bottom notes of green tea, oak moss, cedar wood and sandalwood, among others. It was criticized by those who didn’t like it for ultimately being, as one review went, “so intent on being gender-neutral from a perfume aesthetics perspective, that it literally comprises notes that act to neutralize each other, making the most anonymous and androgynous of beige pleasantries ever smelled at the time.”

But that was exactly the point. It didn’t call attention to itself. It lolled unidentifiably on the skin.

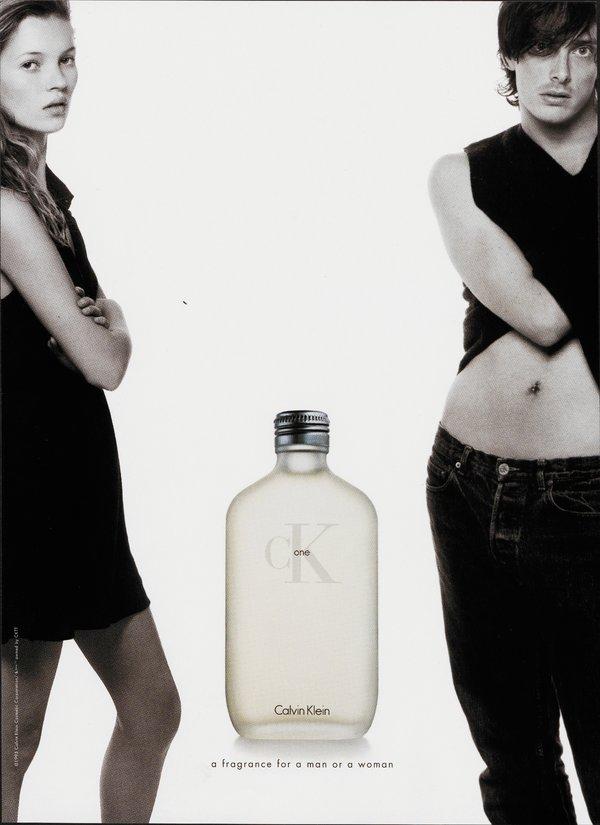

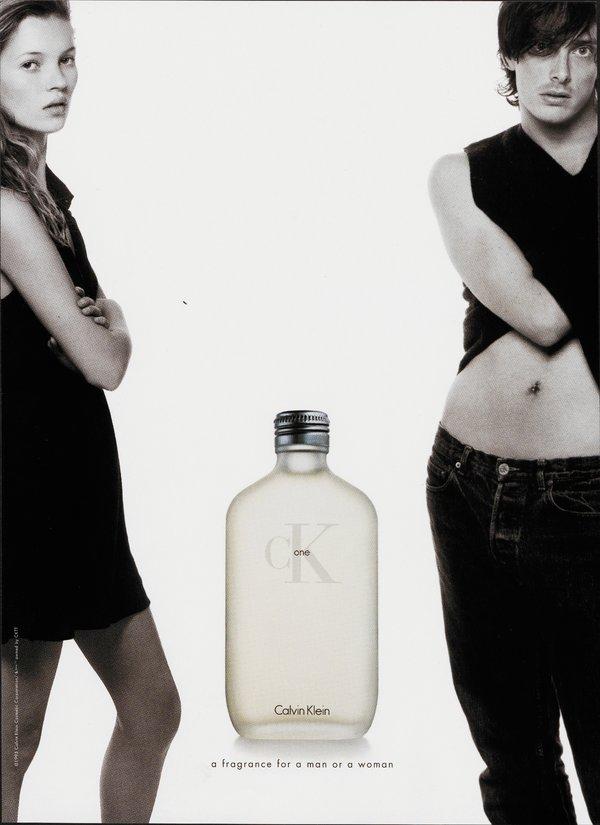

Creditvia Calvin Klein

The bottle was part of it: a frosted glass flask with the thin, lowercase but architectural initials ck (a modified version of the Futura Light font, which pretty much says it all) etched on the front and a screw-on top. It looked like the kind of cheap rum you’d keep in your back pocket; dressed-down like CK, minimal in the Calvin mode, hinting at misbehavior without necessarily doing it.

And so, of course, were the ad campaigns. Shot by Steven Meisel in black and white, they were inspired by a 1969 Richard Avedon photograph of Andy Warhol and the denizens of the Factory. “I wanted to capture a liberal and rebellious attitude, featuring unique people, for our new anti-perfume,” Calvin Klein told Yuka Yamaji in an interview for the Phillips auction house when a book on his photographs was released. “I knew Steven could do that.”

The resulting images featured a rotating cast of weedy, lank boys and girls of all sizes, shapes and shades seemingly free of makeup and artifice, some with long hair, some with shaved heads, sometimes shirtless, sometimes crawling around on the floor for no apparent reason, sometimes kissing, sometimes jumping, often talking.

Kate Moss was there (she was the original spokesmodel, intoning “The only one, CK One, a fragrance from Calvin Klein” at the end of every ad), as well as Jenny Shimizu, the tattooed, openly gay model, and Stella Tennant, the grungy British aristocrat and, every once in while, a more mature fashion insider like Polly Allen Mellen, the fashion editor known for clapping with her hands over her head when excited.

Though its dominance could not last — the scent wheel turned, and fruits and florals made a comeback at the turn of the millennium — CK One remained a defining fragrance for a subsector of the industry. Calvin Klein-the-brand brought it back in different variations (in 2007, with CK in2u, the “the first fragrance for the technosexual generation,” Tom Murry, then the Calvin Klein chief executive, told The New York Times; in 2011 as a lifestyle spinoff). But it never had quite the resonance it had at its introduction, when age group and olfaction had a meeting of the minds.

As Quentin Crisp, the then 80-something flamboyant British writer and actor who inspired the Sting song “Englishman in New York,” said in an early TV ad for the original scent, “What does it all mean?” He was talking about the scent, sure. But also about the whole darn situation.