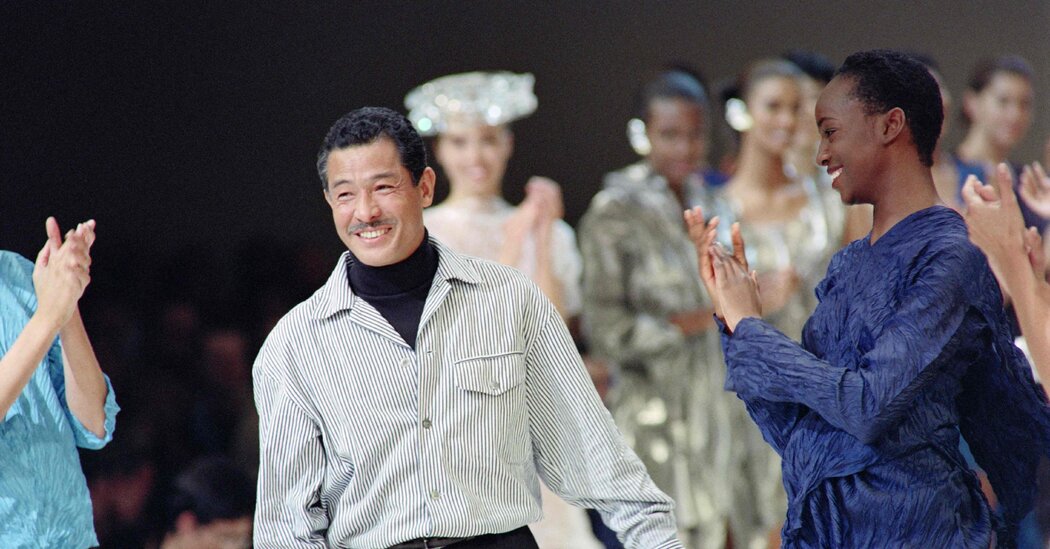

TOKYO — Issey Miyake, the Japanese designer famed for his pleated style of clothing and cult perfumes, and whose name became a global byword for cutting-edge fashion in the 1980s, died on Friday in Tokyo. He was 84.

The death was announced on Tuesday by the Miyake Design Studio, which said the cause was liver cancer.

Mr. Miyake is perhaps best known for his micro pleating, which he first unveiled in 1988 but has lately enjoyed a surge in popularity among a new and younger consumer base.

His proprietary heat treating system meant that the accordionlike pleats in his designs could be machine washed, would never lose their shape and offered the ease of loungewear. He also produced the black turtleneck that became part of the signature look of Steve Jobs, the Apple co-founder.

His Bao Bao bag, made from mesh fabric layered with small colorful triangles of polyvinyl, has long been an accessory of choice for creative industries.

Released in 1993, Pleats Please, a line of clothing featuring waterfalls of razor-sharp pleats, became his most recognizable look.

Mr. Miyake’s designs appeared everywhere from factory floors — he designed a uniform for workers at the Japanese electronics giant Sony — to dance floors. His insistence that clothing was a form of design was considered avant-garde in the early years of his career, and he had notable collaborations with photographers and architects. His designs found their way onto the 1982 cover of Artforum — unheard-of for a fashion designer at the time — and into the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Mr. Miyake was feted in Japan for creating a global brand that contributed to the country’s efforts to build itself into an international destination for fashion and pop culture. In 2010, he received the Order of Culture, the country’s highest honor for the arts.

Kazunaru Miyake was born on April 22, 1938. He walked with a pronounced limp, the result of surviving the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, his hometown, on Aug. 6, 1945. His mother died three years later from radiation poisoning.

Mr. Miyake rarely discussed that day — or other aspects of his personal history — “preferring to think of things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy,” he wrote in a 2009 opinion piece in The New York Times.

He graduated in 1963 from Tama Art University in Tokyo, where he majored in design. After studying in Paris during the student protests of 1968, and a stint in New York, he founded the Miyake Design Studio in 1970. He was one of the first Japanese designers to show in Paris and was part of a revolutionary wave of designers that brought Japanese fashion to the rest of the world, opening the door for later contemporaries like Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo.

He often stressed that he did not consider himself “a fashion designer.”

“Anything that’s ‘in fashion’ goes out of style too quickly. I don’t make fashion. I make clothes,” Mr. Miyake told the magazine Parisvoice in 1998.

“What I wanted to make wasn’t clothes that were only for people with money. It was things like jeans and T-shirts, things that were familiar to lots of people, easy to wash and easy to use,” he told the Japanese daily The Yomiuri Shimbun in a 2015 interview.

Still, he was perhaps best known as a designer whose styles combined the discipline of fashion with technology and art. His animating idea was that clothes should be made from one piece of fabric, and he pursued designs — such as his famous pleats — that incorporated new techniques and fabrics to accomplish that ambition.

There was no immediate information detailing Mr. Miyake’s survivors. A famously private person, the designer was known for his close relationships with his longtime co-workers and collaborators, whom he credited with being essential to his success. He was most closely associated with Midori Kitamura, who started as a fit model in his studio, worked with him for nearly 50 years and now serves as president of his design studio.

Throughout his life, “he never once stepped back from his love, the process of making things,” Mr. Miyake’s office said in a statement.

“I am most interested in people and the human form,” Mr. Miyake told The Times in 2014. “Clothing is the closest thing to all humans.”

Hikari Hida contributed reporting from Tokyo.