Just to get it out there: Yes, bacon is on the list.

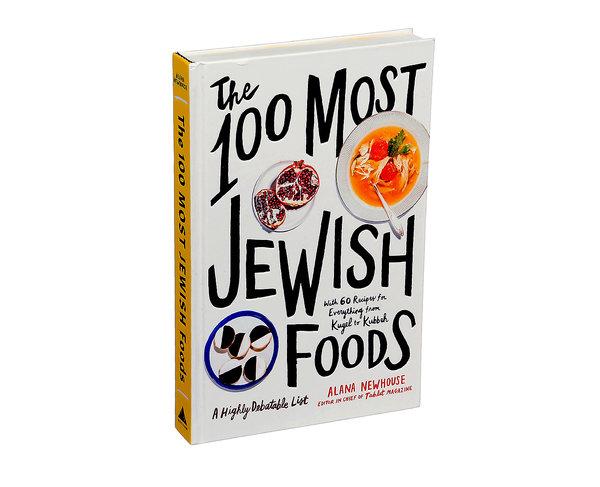

“The 100 Most Jewish Foods: A Highly Debatable List” is a new book from Alana Newhouse and Tablet, the innovative and occasionally irreverent online magazine about Jewish culture.

Ms. Newhouse, Tablet’s founder and editor in chief, said that she and a team of editors initially assembled this quirky collection of essays as a web feature, starting with a call-out to all the writers on food, Jewish identity or both that they could think of. (Sixty recipes were added for the book, published by Artisan in March.)

They knew from the outset, she said, that just as not all the writers would be Jewish, not all the foods would be kosher.

“This is a list of cultural touchstones, the things that define Jewishness,” she said. “How could we not include the one thing that is the most taboo, the most charged?”

So, bacon belongs here, alongside shrimp cocktail and cheeseburgers, in the entry for “treyf” — foods that are never acceptable for Jews who observe kosher laws, such as pork, shellfish and any combination of meat and dairy at the same meal.

The initial shortlist had 300 to 400 entries. How to narrow it down? The editors had to be wary of weighting the list toward Ashkenazi foods, from the Central and Eastern European Jews who carried bagels and babka along on great 19th- and 20th-century waves of immigration. Those might be the most Jewish-American foods, but the much older global diaspora of Jews has pulled in food from Yemen, India, Spain, Greece, Tunisia and beyond.

“The 100 Most Jewish Foods” was published in book form in March, with 60 new recipes.CreditSonny Figueroa/The New York Times

Even within the Ashkenazic world, deli foods alone had 50 spots on the shortlist.

Solomonic choices had to be made. Rye bread or pumpernickel? (Goodbye, pumpernickel.)

Rabbinic debates had to unfold. Is coleslaw a pickle? Are corned beef and pastrami two entities, or just different treatments of one food? (Both are made from salted brisket of beef.) Chicken soup and matzo ball soup were deemed two foods, not one.

“Jewish texts are rooted in arguing,” Ms. Newhouse said, referring to the Talmud, the vast commentary on the teachings of the Torah, written by numberless rabbis over centuries, that is the primary source of Jewish philosophy and law. “Why should this one be any different?”

In the end, most entries turned out to be quite lighthearted.

There are celebrity pairings: Zac Posen on beets and borscht (an ode to color), Dr. Ruth Westheimer on pomegranates (an ode to fertility); Joshua Malina on gribenes (crispy bits of chicken skin that are themselves an ode to chicken fat).

There are unlikely ones, like Eric Ripert, the great French seafood chef, on gefilte fish; Edward Lee, the Korean-American chef, who fell in love with chopped liver as a kid in Brooklyn, long before he had any idea what it was; and Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs, the self-declared WASPs and founders of the website Food52, who suffer from brisket envy. (They grew up on pot roast, which employs lean, boneless chuck instead of fatty, juicy brisket.) “WASPs love their unforgiving meats, just as they love stony silences at the table,” they conclude.

Many spots had to be reserved for the foods that are mentioned in the Torah and still part of Jewish observance: honey, apples, wine, lamb. Also, foods specific to Passover, which begins on Friday night: matzo, horseradish and haroseth, the sweet fruit-and-nut paste that represents the mortar used by Jews as enslaved bricklayers in ancient Egypt.

Space was made for the sacred foods of the Ashkenazi Jews, from Eastern Europe — bialys, lox, seltzer, cheesecake — as well as foods of the Sephardic-Mizrahi (Mediterranean) diaspora: Persian rice, Tunisian lamb-and-bean stew, Roman fried artichokes.

Cheesecake also appears on the list, a creamy, sweet counterpoint to braised brisket. CreditEtienne Voss/Getty Images

And of course, the ultimate New York Jewish cliché: Chinese food, which belongs to another culture entirely. The entry, written by the musician and chef Action Bronson, is a vivid illustration of the affection Jewish New Yorkers feel for Chinese cooking. Historians argue that this relationship was born in the multicultural tenements of Lower Manhattan at the turn of the 20th century, where Jews embraced the food sold by their Chinese neighbors as less self-evidently treyf than the Italian and Polish storefronts that held sausages and ham.

Then there are the head-scratchers, which make the most interesting reading.

Canned tuna fish? It was one of the first American convenience foods to receive kosher certification. As families began to move out of Jewish enclaves, to travel and to eat at nonkosher restaurants, canned tuna and salmon went along and became a familiar, safe and nourishing staple.

Hydrox sandwich cookies? Until 1997, Oreos contained a bit of lard in their fluffy white filling. Generations of children in kosher households knew only Hydrox — which, it turns out, were actually invented first.

Carob? Marjorie Ingall, a regular Tablet contributor, said some foods are on the list mostly because they evoke nostalgia, like the carob pods from Israel that used to appear at Jewish-American schools in the 1970s and ’80s.

“Our feelings about Israel were relatively uncomplicated then” she said. “All we knew was that it was sunny, and the Jews there were scrappy, and they looked like Paul Newman.” (Mr. Newman, who was born Jewish, starred in “Exodus,” a 1960 Hollywood blockbuster about the founding of the state of Israel.)

Long before Israeli clementines and cherry tomatoes were sold in American supermarkets, the fibrous dried pod of the carob, a tree that is native to Israel, had to represent all the fruits of the Holy Land at the spring holiday Tu Bishvat.

“Even though it was dry and brown, it was very special,” Ms. Ingall said. “If you chewed it long enough, you got the tiniest hint of chocolate, and that was a kind of victory.”

Unlike other lists that Tablet has published — of Jewish books, songs and films — this collection is made up of not the “greatest” or “best,” but the “most” Jewish foods.

That’s a good thing, because it would be hard to argue that Sweet’N Low, for example, is the best food in any category. But generations of American Jews grew attached to the cheery pink packets their mothers and aunts carried in their purses, weapons to battle the effects of a lifetime of rich, starchy Jewish-American food.

“People would eat meals of brisket and kugel and cheesecake, but they’d replace the half-teaspoon of sugar in their coffee,” Ms. Newhouse said. (Also, the father-and-son team who invented it in the 1950s? Jewish.)

But food is different from books, music and film. While stories and songs are elements of virtually every human society, food has defined Jewish heritage in specific ways. Because Jews lived within cultures that were not their own, and where they were not always welcomed, kosher food became a defining marker of difference.

For example, adafina. After the Spanish crown forcibly converted or expelled all the Jews in Spain in 1492, the Inquisition sent prosecutors searching for Jews practicing in secret, armed with lists of kosher practices. They searched out homes where olive oil was used for frying instead of lard, or where a paella was suspiciously lacking in shellfish. But if a housewife made adafina, a spiced stew of meat and vegetables often cited in Inquisition records, inspectors would be hard pressed to know exactly what the ingredients were.

“How could we not be obsessed with food,” Ms. Newhouse said, “when so often it has been a life-or-death matter?”