T’s May 19 Travel issue is dedicated to pasta in Italy, diving deep into the culinary traditions, regional variations and complicated history of the country’s national symbol. Click here for a field guide to stuffed pasta, as an accompaniment to this article.

FOR MUCH OF Italy’s history, ravioli was a luxury reserved for banquet tables or feast days. All pasta was a rarefied food in the Middle Ages, but few forms captured the popular imagination as completely as stuffed pasta, considered the noblest of the species. In “The Decameron,” a 14th-century collection of stories by Giovanni Boccaccio about a group of young Florentines who abandon the city for the countryside during the plague, one of the characters, Maso del Saggio, describes an idyllic landscape to entertain the friends: “On a mountain, all of grated Parmesan cheese, dwell folk that do nought else but make macaroni and raviuoli.” Centuries later, every corner of Italy has its own version of filled pasta, which is broadly referred to as ravioli throughout the country. The “Encyclopedia of Pasta” (2009), the Italian food historian Oretta Zanini De Vita’s decades-long effort to catalog Italy’s most popular food, identifies more than 80 types of pasta ripiena (“stuffed pasta”), allowing for countless variations.

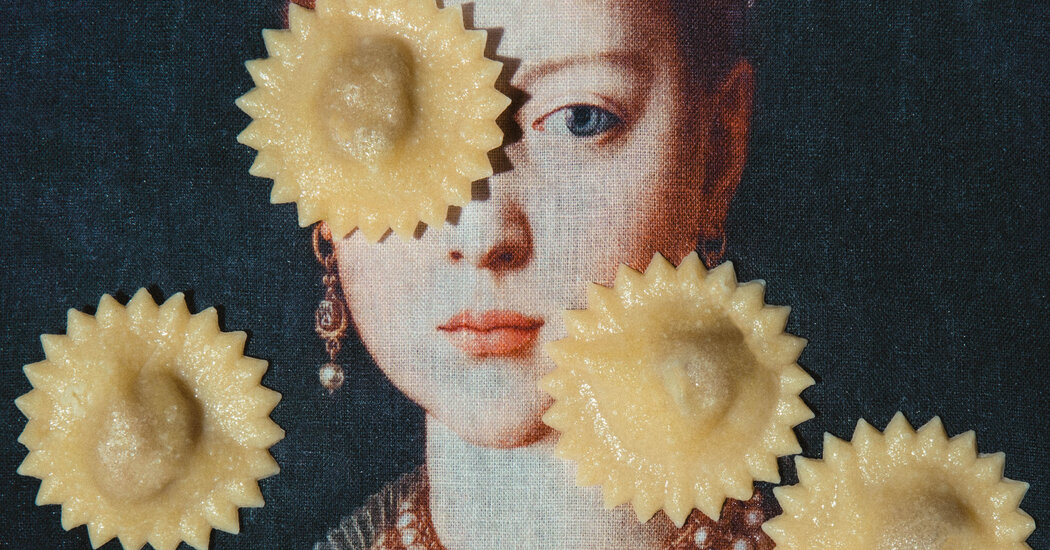

Stuffed pasta seems to particularly lend itself to creative interpretation. There are those filled with sweetbreads, pancetta, pears, chard, winter squash or mint-scented ricotta; twisted at the ends like a candy wrapper or serrated on the edges; folded into a triangle or rectangle or made to resemble a coin, a hat or a handkerchief; boiled in salt water or fried and simmered in milk. Sometimes the dough is kneaded with wine, olive oil or spinach.

Until Italy’s unification in 1861, its territory was carved up into several kingdoms, duchies and city-states, each with its own culinary practices. “Pasta may be the country’s pre-eminent food, but that doesn’t make it a unifying dish,” writes the cookbook author Carol Field in the foreword to the “Encyclopedia of Pasta.” “If anything, the hundreds of divergent shapes accentuate Italy’s regional differences and draw attention to the distinctions that define local identities.”

I’d long wondered how one species or subspecies might take hold in a certain area but not another just next door, and how a dish so deeply rooted in a place might morph over time, even if it often didn’t travel more than a few miles. I wanted to know what was behind this “fanatical attachment to tradition,” as the food historian Luca Cesari has called it. Last November in Piedmont, one of the northwestern regions especially known for its stuffed pasta, I set out to trace the origins and evolution of one local specialty, agnolotti del plin, shaped like a tiny, bulging envelope and traditionally stuffed with meat (typically a combination of veal, pork and rabbit), seasonal greens (maybe savoy cabbage, escarole, spinach or borage), eggs and Parmesan. It’s an unusually demanding type of pasta to construct and is particularly ubiquitous in the area known as the Langhe, a hilly swath of land planted with row after row of nebbiolo grapes in the southern Piedmont, about an hour’s drive south of Turin. First documented here in the mid-1800s, agnolotti del plin (in the Langhe dialect, plin means “pinch”) has only grown in popularity in the past few decades, and now populates virtually every menu, Sunday lunch or holiday feast in the area.