Six years ago, Irina Shayk was eight months pregnant and living in Los Angeles when she decided it was time to learn to drive. She was 31, a supermodel, living with her then partner Bradley Cooper, and until that point she’d relied on Ubers without hesitation. But now the back seat made her nauseous, and the whole practice seemed ridiculous. She was a grown woman.

She woke up one morning and decided: “That’s it.” She got her learner’s permit and practiced on Sunset Boulevard, hands at 10 and 2, her growing belly wedged behind the steering wheel. She gave birth to her daughter weeks later, but remained fixated on obtaining her license.

Shayk took 10 lessons, two hours each. When it was time to schedule her road test, people told her to choose an area with few pedestrians to make for a less stressful exam. And a few advised her: Avoid Santa Monica. Too crowded. “So I was like, ‘I want to do it in Santa Monica,’” Shayk says. “‘I want to be ready for everything.’” She took the test. She passed.

Shayk has long since moved to New York, where she seldom drives. She and Cooper have split, although the two remain devoted parents to their now kindergartner, Lea. You have perhaps seen that commitment in action. This summer, paparazzi captured their Italian vacation together with a Werner Herzog–like zeal for documentation.

Providing ample fodder to the tabloids has become a full-time job for some, but Shayk is still a working model. Despite her start in Sports Illustrated and the contention that her look was “too commercial” for high fashion, she has been cast of late in ads for Marc Jacobs and Versace. Furla tapped her to lead its fall 2023 campaign. This past summer, she served as the face of a new Fendi capsule collection. The driver’s license triumph is thus just one example: Irina Shayk—she wants it, she gets it.

I meet Shayk 24 hours after she marches down the waterfront in Michael Kors’s show at Brooklyn’s Domino Park during New York Fashion Week, and about 12 hours before she jets off for London. We sit down for lunch at Via Carota, not far from where she lives in the West Village. She arrives wearing a leopard dress (vintage), a toga-like overdress (Yohji Yamamoto), and a bucket hat.

We start from the beginning. She was born in Yemanzhelinsk, a small town in Russia. Her father was a coal miner. Her mother was a pianist and music teacher. Her parents raised her and her older sister in a 378-square-foot apartment. Now she calls it a “humble background,” but it didn’t occur to her then that she was poor: “I never thought, ‘I want to have a different life,’” she says. Her parents instilled in her a deep love of music that fed eclectic tastes. When she unwinds at home, her playlist runs the gamut, from Bob Marley and house music to Tchaikovsky.

Being a model was not on her radar; she barely understood what a model was. But when she was 14, her father came down with pneumonia and deteriorated fast. Shayk has that Russian mettle, and she is not easily ruffled. But she does get emotional when she recalls her grandmother’s devastated reaction to the news that Irina’s father had died. He had been his mother’s only child. “I remember to this day her face,” Shayk says. “She was trying to get organized. She was so shocked, and she just held herself together for us.”

After that, Shayk felt a colossal responsibility to ease the burden on her mother, who was now a single parent with two daughters. She spent a month painting hospital window frames, earning the equivalent of $10. She handed out flyers in stores. “My dad had always wanted to have a boy,” she says. “He loved us, but when he died, I kind of felt like, ‘I have to take care of the family.’” The role suited her, in a way. “I always thought I was born in the wrong body,” she says. “I hated being a girl. I remember fights with my mom; she wanted to dress me in something flowery. I wanted dark colors and something solid. It wasn’t that I wanted to be a boy, but I felt like, ‘I don’t belong to my body.’” Her sister was obsessed with hair and makeup. Shayk felt “completely opposite.” She remembers clamping down on her lips as a child, hoping to make them smaller.

Most models start working at age 14 or 15. Shayk finished high school and went to college in Russia. She had no idea what she’d do with a marketing degree, but she knew she wanted out. Her ticket arrived in the form of a modeling scout, who noticed her at the cosmetology school where her sister had enrolled and she had dutifully followed. “He said, ‘You want to go to Paris?’” Shayk remembers.

The first time she set foot on an airplane, she was almost 20. She moved into an apartment with a rotating cast of five or six other women and was given around 60 euros a week. She had few responsibilities and one real ambition: She wanted to earn at least €100. You will just have to take her word for it that that proved difficult because her body—that body—was not met with universal favor. She heard casting directors whisper about her curves and her skin tone. “I had agents who said, ‘You have to cut your hair, lose 20 pounds, and become blonde,’” she says. “And I was like, ‘Absolutely fucking no.’”

Shayk explains her stubbornness in astrological terms. (She’s a Capricorn.) But she knows her father’s death was a factor, too. “You have perspective” after something like that, she says. “Whatever happens in my job, I’m like, ‘Everyone is alive.’” Shayk was resolute: “I was like, ‘I’m not going back to Russia.’” Eventually, she booked a job in Spain, which netted her €1,000. “It was so much money,” she says, still marveling. She sent a couple hundred euros to her mother. “She told all her friends, ‘My daughter bought me a sofa,’” Shayk says.

She was 21 when she made her debut in Sports Illustrated’s 2007 Swimsuit Issue. Now New York is home, but the culture shock at first was considerable. In Russia, her parents had had a garden. She spent her summers learning how to grow tomatoes, cucumbers, radishes, and potatoes, and how to pickle them for winter. When she first landed in America, it was the supermarkets that stopped her in her tracks. “I was like, ‘You can buy potatoes?’” In her town, if you didn’t grow it, you didn’t eat it.

It took Shayk years to break into high-fashion modeling. Harry Josh, a friend and hairstylist, notes few swimsuit models are able to make that transition. “She just is very comfortable and confident,” Josh says. “She knows where she came from. So when she’s given an opportunity, that has allowed her to spread her wings and feel very proud of how far she’s come. Most people never make that crossover.” It’s a nice sentiment. Shayk hates that it’s true. “People, not only in fashion, put you in boxes,” she says. “They put hats on you.” (She points to her own hat for emphasis, which we both pause to admire.)

It was Riccardo Tisci who decided to give her a shot. In 2015, he asked her to meet him in Paris. He was designing for Givenchy at that time and casting an upcoming show. When she walked into the room, “He looked at me, and I looked at him,” Shayk says. “And he was like, ‘Walk.’” Shayk says that certain unnameable people advised him not to hire her, but he countered, “‘No, she’s in.’”

Later, she learned that Tisci had also lost his father when he was a child, and grew up with a houseful of sisters. “We just connect,” Shayk says. She feels a closeness with him that she doesn’t feel with most people. “I don’t have a lot of friends,” she says. “[Even] if you count all your friends on one hand, you’re really lucky.”

She’s grateful Tisci took a chance on her. But she finds the whole practice of categorizing models as either “commercial” or “fashion” grating. “I’m so sorry I did this lingerie job,” she says, mock-contrite. Maybe models born to rich parents can afford to be choosy, but she had a family depending on her. When I suggest that at least that period of desperation is behind her, she cuts me off. “It doesn’t matter even if I’m doing it now,” she says. “I have to pay my bills. I don’t have a rich husband. I don’t have a sugar daddy, so I have to pay.”

And besides, she likes what she does. The makeup artist Isamaya Ffrench tells me that Shayk has a reputation for being hardworking—on time, vibrant to the last shot. “I once stuck hundreds of tiny crystals on her face and décolletage, and she stood patiently the entire time,” Ffrench says. Josh remembers shooting with her in Iceland. “It was the dead of winter,” he says. The brand wanted glaciers in the background. “We were in puffers, sock warmers, finger warmers, the whole shebang. She was in panties and a cashmere sweater.” Shayk looked blue and was shivering. But when the photographer picked up his camera, she lit up. “Her mentality was, ‘You have to get the shot.’”

When her daughter complains that Shayk is leaving for work, Shayk prompts her: “You want to go on vacation, right? You want to go shopping? So I’m going to London. You’re going to be with Daddy, because Mama has to work.” Shayk and Lea speak to each other in Russian, their “secret language.”

It pains Shayk now to see the news from her homeland. Her mom and sister live near the Ukrainian border. Like a lot of Russian families, she has relatives who live in Ukraine, on her maternal grandmother’s side. “It’s devastating,” she says. “All you have to do is pray for better and hope it will be finished soon.”

She would rather focus on what she can control—her work, her family. “Looking at my daughter now, she’s growing up in a completely different environment,” Shayk says. “She lives in the West Village. She went to all these countries in two months. But we want her to know the value of stuff. We want to show our daughter, ‘You have to work hard to get something.’”

Shayk will say very little about her ex, but she acknowledges that both of them came from “normal backgrounds.” They’ve made a concerted effort to give Lea as regular a childhood as possible. She lives in New York, which Shayk likes for its diversity. She walks to school. Neither Shayk nor Cooper employ a nanny.

“We both take Lea everywhere with us,” she says. “She’s super easy. Two days ago, I had to go to the gym, so I just got her a drawing book and said, ‘Mama’s working out.’ She was drawing for an hour. Then we went to the Michael Kors fitting. She met all the girls. Michael gave her a bag. She drew him a kitty cat.”

Even when Cooper is shooting a film, he and Shayk hammer out a schedule that works for both of them. “We always find a way,” she says. And reticent though she may be about discussing their relationship, she will say this: “He’s the best father Lea and I could dream of. It always works, but it always works because we make it work.”

Not all exes are so harmonious, and the week we meet, the internet is raging about whether it’s appropriate for a certain starlet to be going out drinking when she has children at home. I wonder if Shayk has ever encountered that kind of judgment. Her lips purse. No, she does not think women should change their wardrobes or behavior because their children exist. “I’m still the same person,” she insists. A person who still wants to wear sheer dresses and thongs on vacation, and still likes to have fun. Ffrench assures me: “Boy oh boy, can that girl get through caviar!”

The fashion industry brims with people pleasers, but Shayk swears she is not one of them. Social media criticism, Page Six analysis—it comes with the job. “That’s what you get,” she says. “Not everybody is going to like you. And I don’t want everyone to like me. I am who I am. I’m not going to change because somebody who has nothing to do in their life is saying some bullshit about me or how I dress or how I’m parenting. No, get your life together.”

For the most part, she chooses not to react—not even when she sees something untrue. She doesn’t want to encourage the attention. But since we’re here, she tells me, “Nobody wants to write something that is truthful. Sometimes I want to be like, ‘Fuck you. It’s absolutely not true.’…Half of the people who they say I’m dating, I’ve never even met them in my life! These people who are literally evil or have nothing to do, sitting there and writing some bullshit and getting away with it,” she says. “They should go to prison for that.” But this is America, so she moderates: “There should be some kind of punishment.”

Of course, now would be a perfect opportunity for Shayk to clear up some details about her personal life. Are she and Cooper getting back together? Or are things ramping up with her rumored love interest, Tom Brady? It’s a romance that the Daily Mail and the New York Post have been obsessing over like it’s a serialized Austen novel. She smiles—all teeth: “No comment.”

“I share my work stuff because I decided to keep my personal life personal,” Shayk continues. “That’s why it’s called personal, because it’s something that belongs to me. If one day I feel like I want to share it, I will.”

A few hours after I leave our lunch, I see photos in the New York Post of Shayk arriving at Tom Brady’s apartment building, minutes after he arrived. (Though, in late October, Page Six reported the three-month relationship had “fizzled.”)

On the morning of the Kors show, Shayk woke up filled with gratitude. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, I’m so grateful,’” she says. “I’m 37. I’m doing this show.” But then she was like, “I’m so swollen. I have a dress, my arms are showing. My arms are fucked.”

It was her first show after vacation. She pinched a wedge of skin to show me. For the record, her arms look fine. And it is bizarre to listen to a supermodel detail her perceived flaws. But harder to believe than the notion that Shayk doubts herself is the fiction that there’s a single person on earth who loves how she looks all the time.

For her, acceptance means knowing that even the most potent insecurities don’t last forever. She teaches her daughter a version of the same lesson: Feelings pass. “It’s just an emotion,” Shayk says. “It’s so good to acknowledge and to have this kind of conversation with yourself: It’s okay to feel that. It’s okay to look like that. It’s okay. It’s you, and it’s part of being alive.”

Whatever Page Six reports, Shayk insists her best relationship—and her longest-lasting—is the one she has with herself. “It blows my mind,” Shayk says. “I’m like, ‘What do you do for a job, take pictures?’ It’s like, ‘Wait, you’re getting paid?’”

Shayk’s mother made $10 a month teaching 30 kids how to sing. Her father did dangerous, backbreaking work. She’d congratulate herself on how far she’s come, but then she worries she might lose some of her edge. It’s a balance, or perhaps it’s more like a tug-of-war. “Give a little sugar,” Shayk says, laughing. “Now give a little whip.”

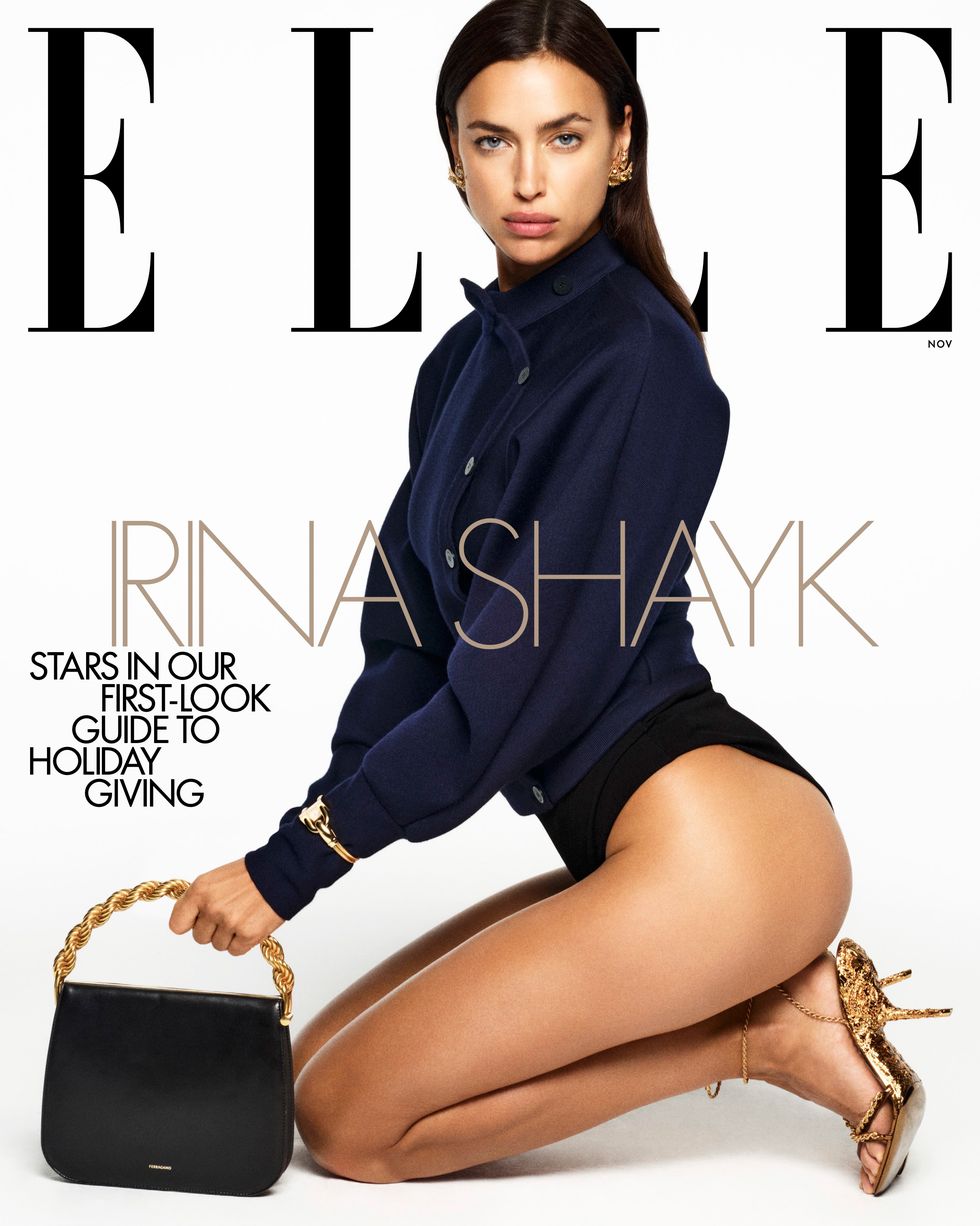

Hair by Bob Recine at The Wall Group; makeup by Fulvia Farolfi for Chanel Beauty; manicure by Rica Romain at Statement Artists; produced by Travis Kiewel at That One Production.

This article appears in the November 2023 issue of ELLE.

Mattie Kahn is a writer whose work has been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Elle, Vogue, Town & Country, and more. She is the author of Young and Restless: The Girls Who Sparked America’s Revolutions.