Blake Nordstrom was a model Nordstrom. He was nice about being competitive and competitive about being nice.

He would wish employees happy birthday a day early, so that he would be the first to do so. He would carry consultants’ luggage without being asked. As a teenager, if he noticed that his brother Peter’s car had gotten dirty, he would wash it; otherwise, he’d say, it would drive him crazy.

As an adult, he would replenish Peter’s woodshed when it was running low. (Peter: “I can order my own wood!”)

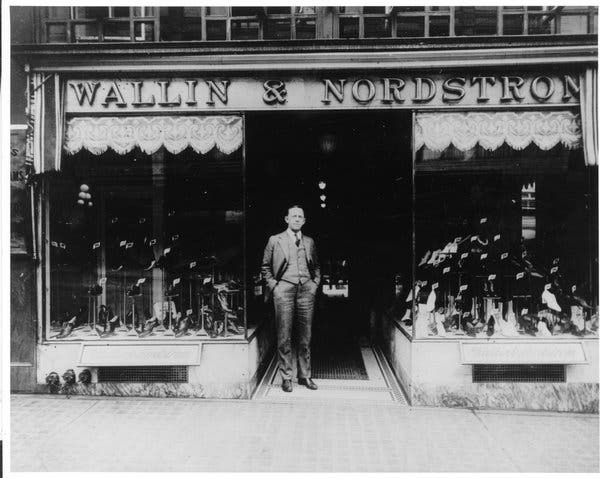

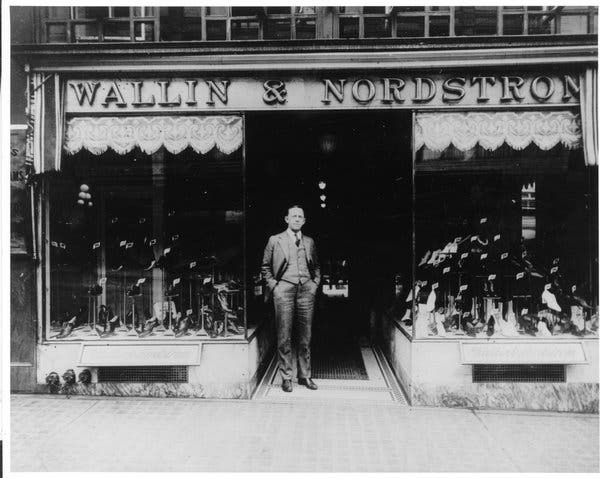

Nordstrom, the department store chain that has been spreading gradually from the Pacific Northwest since it was founded in 1901 by two veterans of the Alaskan Gold Rush, was struggling in the 1990s. It was being run by committee — by multiple people not named Nordstrom.

In 2000, Blake took the reins. He argued that the corporation should cut the fat, oust the consultants and return to its core value of customer service. The company steadied and began to grow again, even as the internet was transforming, or dooming, retail.

In 2012, Nordstrom announced that it would open a flagship store in New York City. Once, the Nordstroms had simply wanted to have the best store on a Seattle avenue. More than a century later, their ambition had expanded with their company.

“If we are going to be the best business of our kind in the world, we’ve got to be in New York,” the 86-year-old family patriarch, Bruce Nordstrom, said recently.

The store opens on Oct. 24. It is a seven-level behemoth on 57th Street and Broadway, near the corpses of Bonwit Teller, Henri Bendel and the gravely wounded Barneys.

Less than a year before the opening of this store, Blake Nordstrom was diagnosed with lymphoma. His decline was swift: Feeling ill during a vacation in January, he and his wife returned home. He died on a Wednesday in Seattle.

Peter Nordstrom and his younger brother, Erik, now run the company. They are the fourth generation of Nordstroms to head the store and, almost certainly, the last.

Meet Pete

Peter’s band Stag shares its rehearsal space with a strip club in Seattle called Dream Girls SoDo. At a recent rehearsal, Peter, who is 6-foot-5 and called Pete by everyone, had untucked his immaculate white dress shirt from his slacks, perhaps in an effort to fit in with the T-shirts around him. But his Dries Van Noten shoes clashed with the dirty sneakers of his bandmates. “The strippers love this,” he said, as the four-piece banged out a version of their song “Pied Piper.”

(Peter, 57, has been in other bands, including one called The Retailers. “Coming up with a band name is perhaps the toughest and worst part of being in a band,” he said.)

The Nordstrom brothers were not particularly rebellious. Peter, who is in charge of the company’s merchandising, has strayed farthest from his family’s natural conservatism. He has broadened Nordstrom’s world, thanks partly to his interest in pop culture.

He didn’t care about schoolwork but knew everything about the television he watched. Sunday nights, he would hide a radio under the covers to listen to the Top 40 countdown. In college, he worked security at concerts, doing what he could to protect the dignity of bands like Rush, Styx and Blue Oyster Cult.

As a buyer in Southern California in the 1990s, he was the first at Nordstrom to purchase Doc Martens and later Birkenstocks. And he has hired employees unconventional for Nordstrom, which tends to promote safely from within.

If Blake’s role was to re-Nordstromify things after the 1990s confusion, part of Peter’s role has been to expand the idea of what Nordstrom can be.

A Crash Course in Department Stores and the Forces That Have Threatened to Destroy Them

Urbanization: With the development of the modern American city came the rise of the department store. It sold just about everything: clothing, home furnishings, books, toys, televisions, electronics, even cars sometimes. The stores were named for the families that ran them, merchants integral to their cities.

Suburbanization: As Americans departed cities for suburbs, there arose a new kind of shopping center to which they could drive and shop their little midcentury hearts out. By the end of the 1950s, a name was in circulation for these wonderlands: malls. Savvy, quick-moving department stores found a home in malls. Others, like Best and Co. (New York) and Boggs and Buhl (Pittsburgh), went out of business.

Specialization: The suburbs opened up access to real estate and along came the specialty stores, around the 1980s. A trek to a department store to get consumer electronics, or books, or toys became unnecessary. Smaller retailers, more agile and expert in the goods they sold, didn’t have to compete with one-stop destinations anymore. Goodbye, Wanamaker’s (Philadelphia) and Thornton’s (Abilene).

Digitization: In 1994, Jeff Bezos drove halfway across the country to the Nordstroms’ hometown. Within several years, the business that would fundamentally change retail had gone public. Twenty-five years after Amazon was founded, the remaining department stores struggle to compete. With their traditional customers aging, they, like other legacy businesses (glossy magazines and newspapers, for instance), are staring down a cliff. Once those customers are gone, who will shop at department stores?

Online-ish

Nordstrom is fairly good at the internet, as far as enormous corporations run by the middle-aged go. A third of its sales are made online, it says. The company has figured out what in retail is called, horrendously, “omnichannel,” which means coordinating between selling online, offline and in between. The Nordstroms don’t love the term.

“Customers, they don’t even know what you mean when you say ‘channel,’” said Jamie Nordstrom, 46, Pete and Erik’s cousin and the company’s president of stores. “They want great experiences, they want access to the best merchandise, and on and on and on. They don’t think about channel.”

There’s a Venn diagram of life online and offline, and retailers are starting to understand that monopolizing its center is good for making money. This is exemplified in a new type of store called a Nordstrom Local, where no clothes are sold. They are strange little places that offer, along with the free shipping and returns the company is known for, the chance for customers to do errands that are best accomplished in person.

Such as: tailoring, styling and, at the Nordstrom Local on the Upper East Side, stroller and car-seat cleaning by something called a “tot squad.”

Nordstrom Locals started two years ago in Los Angeles. Customers seem to like them. Analysts see them as the future. Kelsey Groome, a retail consultant, said they were key to the success of the entire Manhattan enterprise, and an extension of Nordstrom’s much-admired “commitment to omnichannel.”

Meet Erik

“He’s the smartest,” Bruce Nordstrom said of his youngest son. Also: “In college he was 6-foot-5, 170 pounds and he ate like a pig.” Additionally, Erik, who will turn 56 the day the New York store opens, is the funniest Nordstrom, which takes time to see because Erik is also the shyest.

When, during a recent family lunch, the HBO show “Succession” (which focuses on a family-run company) came up in discussion, he apologized for the fact that his own family was so dull by comparison, with the subtle Swedish irony that is key to Nordstrom humor.

Erik speaks thoughtfully and deliberately on most any subject but clams up when the subject is himself. Asked what his responsibilities are at the company and what he hopes to accomplish each month, he asked for clarification. “Me, personally?” Then, he gave his stock answer: “Well …”

All Nordstroms are competitive. But Erik was the best at school. Also, he was the best basketball player of the three according to his high-school coach, who noted in particular his adaptability.

That quality helped when Erik was dispatched to oversee the Nordstrom store at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minn., in the early 1990s. He thought the post “seemed super-random.” His apprehension grew when an uncle predicted sales of $30 million in the store’s first year. Erik had previously managed a store with sales over $50 million.

“I was crushed,” Erik said. “Did I get demoted and not know it?”

The Mall of America was viewed skeptically by Minnesotans. Their beloved department store, Dayton’s (which, after a merger, gave birth to Target), wasn’t there. Nordstrom’s mall store was competing for tourist money with other national retailers.

But the company focused on service, which, Erik explained, meant that customers would return.

“Local people started coming,” he said. “And they weren’t necessarily coming and going on a roller-coaster ride after shopping.”

The store sold more than $60 million worth of merchandise in its first year.

The Retailers

Nordstrom family members are an infinitesimal percentage of Nordstrom employees. And in recent years, Nordstrom employees have been asked, many of them by Peter Nordstrom, to remake the way it does business. Here are three people who attempt that:

Teri Bariquit: Recently became the company’s first chief merchandising officer. Helped save Nordstrom from perennial overstocking problems in the 1990s. Now figures out how Nordstrom can compete, with “strategic pricing of brands,” “exclusive distribution with partners” and other tricks. Talks fast.

Olivia Kim: Former superstar buyer at the avant-garde emporium Opening Ceremony, now Nordstrom vice president of creative projects. Helps normal people understand how to wear fancy clothing by designers like Chanel. Likely the coolest person who works at Nordstrom. Doesn’t care.

Sam Lobban: British retail veteran who came up at the men’s wear site Mr Porter. Loves “omnichannel”; makes up for it through fervent fandom of the British proto-punk band Suicide. Wears all black. Vice president of men’s fashion.

Stockroom Boys

Ask a Nordstrom about being a Nordstrom at the company that bears his name, and he is likely to underplay its importance.

Peter: “I never felt like I got something that I didn’t really deserve. I was slugging it out just like everybody else, and I don’t know that I was any better than anyone else but I certainly didn’t think I was any worse.”

Erik: “It was never ‘graduate from college and who’s going to get the corner office, whose parent is going to push for that.’ It was: We were selling shoes and ‘you can be a third assistant manager.’ And then ‘you can be a second assistant manager.’ It really did feel very natural.”

The culture in the shoe stockrooms where the brothers started at the age of 12 was competitive and thoroughly male. After work, Nordstrom colleagues tended to go out for beers.

At those gatherings, the lines between the professional and the personal, already far less carefully maintained than today, barely existed. Dating within Nordstrom used to be widespread and many higher-ups met their spouses there, the company said; there are now explicit rules covering work relationships.

In 2001, a former employee and ex-girlfriend of Peter’s filed a lawsuit claiming that he had harassed her. The two had started dating in 1993 and had seen each other on and off for about seven years. She was well known to the family.

A court said no reasonable person “could conclude that she was anything other than a willing participant in a mutual, consensual relationship.” (She sued The Stranger for defamation, and lost. Multiple attempts to reach her for this story were unsuccessful.)

The Stranger reported that another ex-Nordstrom employee had filed a lawsuit against Peter, in San Diego. The lawyer that woman initially retained stopped representing her.

The plaintiff did not show up for court and the lawsuit was dismissed, according to court documents reviewed by The New York Times. She did not respond to requests from The Times for comment.

The Stranger also reported that Peter had dated at least 13 employees since he started working for the company as a teenager. Nordstrom disputes that number, saying he dated five.

Peter, who was married in 2007, seemed to refer to this history unprompted when asked a general question about career regrets.

“I was probably too socially connected with people I worked with,” he said. “I was a guy in my early 30s, a single guy in my early 30s at Nordstrom. There was a real social thing.”

Asked if he was talking about dating co-workers, he said, “Well, sure. And you know we had parties and were going out for beer together. It was all harmless stuff. It is what it is. It’s a very social place, and I was a young person just trying to do the best I could. I took my work seriously and I worked hard at it but I also felt like if I had to do it over again, knowing what I know today, I probably would have had a little more distance.”

‘A Bunch of Dumb Swedes’

In the midst of fashion week last month, Nordstrom hosted a dinner with the industry website Business of Fashion. The high-profile guests were representative of Nordstrom’s importance to the fashion industry.

Tommy Hilfiger, for instance, was present, as were Tory Burch and the models Karolina Kurkova and Ashley Graham.

Peter gave a toast, in which he attempted to explain why the new flagship was so important. “I guess my response to why now and why here is we’re big believers in New York,” he said.

Chris Wanlass, 43, will run the New York market, which along with the new store includes the men’s store that opened in 2018 and the Locals. (New York’s Nordstrom Racks — the company’s discount stores — will be run separately.) Mr. Wanlass has used his career at Nordstrom to move from Utah County, Utah — where “Footloose” was filmed — to some of the bigger cities in the world.

When asked how he would explain the New York store’s importance to a 12-year-old, he said that it “was critical to give us that visibility globally, and to be taken seriously.”

Bruce Nordstrom put it plainly.

When he started working at the company, during World War II, there were two stores and being the best was a local matter. Then, in 1957, Nordstrom expanded to Oregon and it was a regional matter. And in 1978, it opened in California, where the investment guys, as Bruce called them, made it something bigger.

“I was told in so many words by the experts, you know, ‘you guys are basically a bunch of dumb Swedes selling to another bunch of dumb Swedes, up in Seattle, in the woods up there,’” he said. “‘And you’re going to California? Do you understand how sophisticated and hip it is?’ It got under my fingernails so bad.”

The goal became to be the best department store in the world. And the best department stores in the world were in New York.

A city whose proudest retail once rose from the Jewish dealers of the Lower East Side and the Italian garmentos in Midtown is already host to a bevy of globally oriented, Scandinavian-tinged companies and products, to H&M and its holdings, Ikea, Flying Tiger Copenhagen, cardamom buns and hygge. This week, Nordstrom will join them.

The Nordstrom Legacy

Asked what it’s like to see Peter and Erik running his grandfather’s company, Bruce brought up his eldest son.

“I had a son Blake too,” he said. “And he was the best out west. Just a tremendous young man. And dies at the age of 58. That’s not the way it’s written up there. And I’m 86 now and I’m still flopping around like I am. I would have traded places, if someone would give me a chance.” His voice broke.

Even apart from Blake’s death, Nordstrom has had a trying year, with sales down and dim prospects for retail depressing the company’s stock. Erik said that, especially given the challenges, he still reflexively reaches for Blake’s advice all the time.

“Something will come up and I’ll have this thought in my head like, ‘Oh, Blake’s better at that,’ or ‘That’s Blake’s strength’ and then, ‘Oh, I can’t go there.’ And the reason I can’t go there is because he’s not here. And the emotional part comes.”

But as Peter and Erik mourn their brother’s absence, they feel lucky to work in a place where so many people know who he was. Part of him is in the culture of Nordstrom, they say. In the New York store, casts of his footprints will be in two separate places, one looking out over the city and the other in the shoe department.

Peter and Erik feel similarly about their own legacies, about likely being the last Nordstroms to run the company. Though Peter’s children are young, he and Erik seem fairly sure that their successors will not be Nordstroms.

“I just think it’s a different deal for our kids,” Peter said. “There’s a lot of work to get from here to there.”

It’s true that in the absence of total failure, the Nordstroms were headed for the C suite. But it took this generation more than 20 years to get there. If their children were interested, they say, it would take just as long.

Instead, the family sees the future of its store in people like Olivia Kim and Sam Lobban, Teri Bariquit and Chris Wanlass. The Nordstrom lineage comes across in conversation with these non-Nordstroms. They all share the Nordstrom dedication to their work and a certain Seattle-style modesty, a quality not natural to the city in which the company is making its latest bet.

“New Yorkers are funny,” Bruce said. “They want to see everything and experience things but if they don’t like it, they’re gone. This store, people are going to go out and say to their neighbor, ‘Go out and see Nordstrom. It’s something!’ And it is something.”

He paused.

“It better be something,” he said.

Candice Reed contributed reporting. Susan Beachy contributed research.