Hudson Valley bricks are an “inescapable presence” in New York City, George V. Hutton, a retired architect, wrote in his book about the once-booming industry.

Mr. Hutton, despite his clear bias — he was from a prominent brickmaking family in Kingston, N.Y. — was not wrong.

It’s fairly safe to assume that any brick building constructed between 1800 and 1950 includes some form of sediment from the banks of the Hudson River. The Empire State Building, the Museum of Natural History, the arches of the Brooklyn Bridge, Delmonico’s and countless residential buildings — including the Parkchester development in the Bronx and Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan — were all built from Hudson Valley bricks.

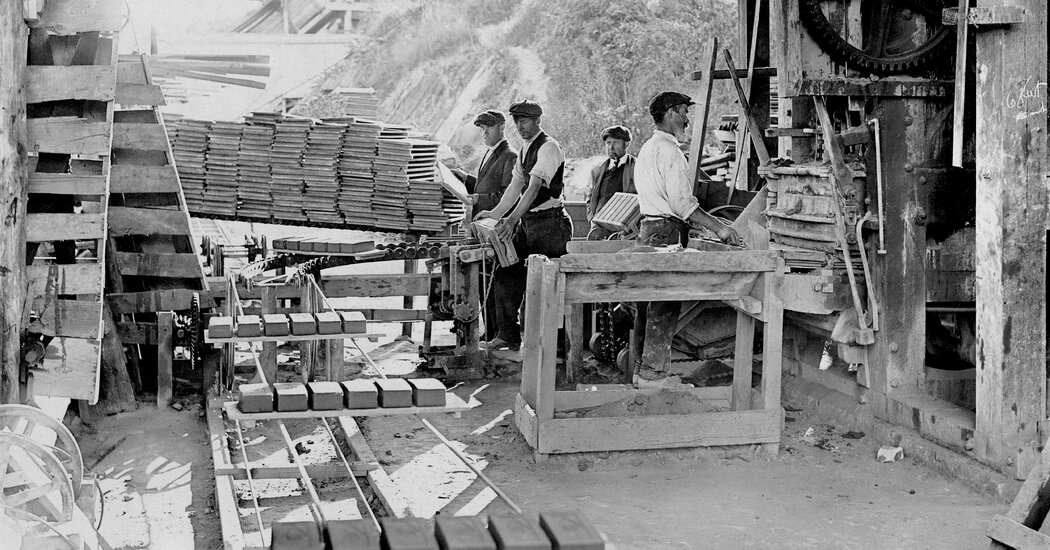

During the industry’s turn-of-the-century heyday, there were more than 135 brickyards along the riverbanks mining seemingly endless deposits of clay. In Ulster County alone, 65 brickyards were once in operation. In 1904, 226,452,000 bricks came out of Ulster County, according to its archives office, and most of them were sent directly to New York City.

Hutton Company Brick Works in Kingston, which opened in 1865, was the longest-running brick plant in the Hudson Valley. When it stopped operations in 1980, representing the end of an era, the grounds were all but abandoned.

But plenty of artifacts remain. There are three massive steel-frame kiln sheds, partly sunken barges and a crane that once transferred bricks onto barges. These old crumbling, rusted out sites in Kingston provide physical proof that brick factories ruled the local economy just a century ago.

“This was basically all a skate park,” said Taylor Bruck, 30, who grew up in Kingston and whose great-great-grandfather worked at a brickyard in Glasco, 10 miles north. He is also the archivist for Ulster County and Kingston’s official historian. “All the kids from the neighborhood that needed space to play, we’d come here.”

The 73-acre riverfront site is also awash with old bricks. Instead of sand or rocks, the shore is blanketed with the vintage rectangles, or chunks of them. Underwater lie thousands more. On the grounds, brick corners poke up from the grass, and anyone digging just a few inches is likely to uncover a brick or two.

It’s an urban explorer’s dream. Or it was. Seven years ago, a developer saw some potential in the derelict brickyards and bought the property. Since then, Karl Slovin of MWest Holdings has carefully salvaged, remediated and restored what he could, including the kiln sheds, crane, pavilions and a few brick buildings. In 2014, he opened an events space among the ruins, where Bob Dylan performed three years later.

And now the old site has become a boutique hotel and retreat. This month Mr. Slovin and his operating partner, David Bowd of Salt Hotels, opened Hutton Brickyards, which has 31 stand-alone cabins, an open-air restaurant in one of the old pavilions, a spa and walking trails where you might spot remnants from the factory.

“The brick is woven throughout the guest experience, and we’re really trying to honor that past,” said Kevin O’Shea, a founder and the chief creative officer of Salt Hotels.

Hutton Company Brick Works was initially called Cordts and Hutton, after its two founders, John H. Cordts and William Hutton. In the early years, Mr. Cordts was the hands-on owner who lived on-site (in a circa-1873 mansion on a hill above the brickyards, which was recently purchased by Mr. Slovin and will become part of the hotel) and ran things day to day. After Mr. Cordts retired, Mr. Hutton became the sole owner. In 1880, the plant was “one of the largest brickyards on the Hudson between Haverstraw and Albany,” Nathaniel Sylvester wrote then in “History of Ulster County.”

In the 1800s, Haverstraw, in Rockland County, was a brickmaking hub and the site of much innovation. It’s where coal dust was first added to the clay mixture in 1815, which halved burning time in the kilns, and where Richard A. Ver Valen invented the first automatic brickmaking machine in 1852. By the middle of the century, Haverstraw was producing millions of bricks a year.

“At this point, two-thirds of the buildings in New York City were made with bricks from Haverstraw,” said Rachel Whitlow, acting executive director of the Haverstraw Brick Museum. “Most of the Hudson River towns were made with Haverstraw bricks, but New York City got the good bricks.”

Brick had become the material of choice for new buildings in the city ever since two disasters — the Great Fire of 1835 and the Second Great Fire in 1845 — destroyed much of Lower Manhattan. That, plus the construction around the same time of the Croton Aqueduct, which was made entirely of bricks, meant that the clay deposits along the banks of the Hudson were of great value. Factories sprung up in the Hudson Valley, with the number of brickyards nearing 100 by 1860.

By the latter half of the 19th century, thousands of people were employed at the brickyards. The trade offered a good living for many immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Germany, Hungary and Romania.

“You had immigrants from all over the world coming to Haverstraw; they would get off the boat in Ellis Island, and there were people from the brickyards there, telling them, you don’t have to live six people to room, it’s nice and open, and you can have a job,” Ms. Whitlow said. “In one generation, if you were an immigrant, you could have money in your pocket and you could send your children to school, and by the second generation, you were already often investing in something else or you would go upriver and make a new brickyard.”

By the early 20th century, as part of the Great Migration, Black Southerners were also being recruited by brickyard owners, who would pay for their travel expenses.

Most brickyards offered company housing, which then expanded into thriving, engaged communities in or near river towns like Newburgh, Beacon, Kingston and the capital of the industry, Haverstraw.

But on Jan. 8, 1906, tragedy struck Haverstraw: A landslide caused by the continuous excavation for clay killed at least 19 people and destroyed countless streets, shops and houses. To this day, the town holds a memorial service every January for the victims, and exhibitions about the landslide are on permanent display at the Haverstraw Brick Museum, which was founded in 1995 by descendants of brickyard workers.

By the late 1920s, the industry was fading because of the rise of cement, cheaper European imports and even bricks being made in the South. According to Mr. Hutton’s book, the number of brick factories had been cut in half by 1927. The Great Depression and World War II also caused many brickyards to shut down, although the ones that survived enjoyed a postwar boom for a while. By the 1950s, many more were closing.

In 1965, Hutton Company Brick Works was sold to a competitor, who then sold it to another competitor. Fifteen years later, after a brief resurgence in popularity for molded bricks in the 1970s, Hutton was closed by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

As the hotel celebrates its opening this month, Mr. Bruck, Kingston’s historian, is feeling nostalgic. “I think it’s better for the area in general, but it’s no longer ours,” he said of the former skate park and current industrial-chic property. “Knowing what it looked like before and what it is now, they put millions into this place, and I love that they kept everything.”