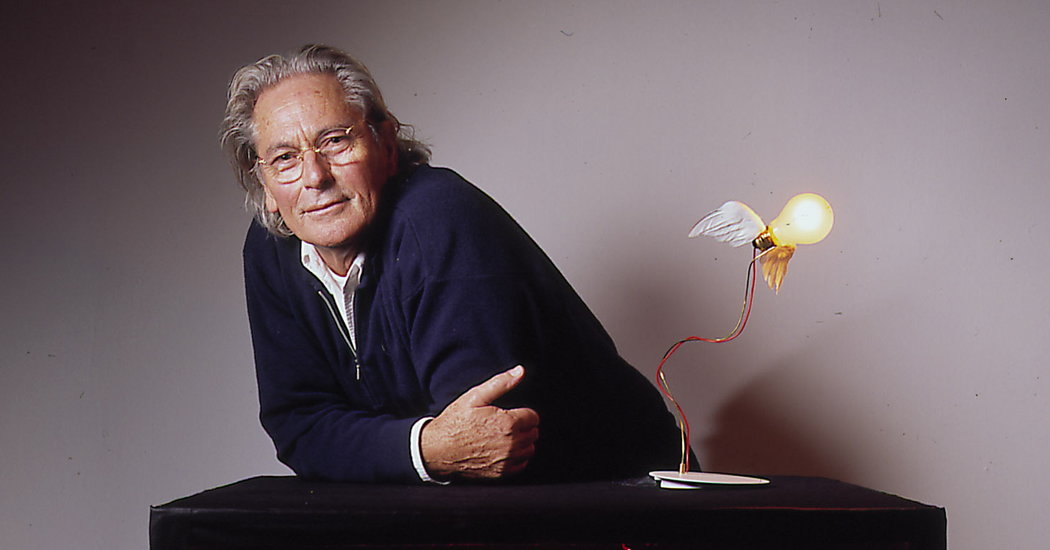

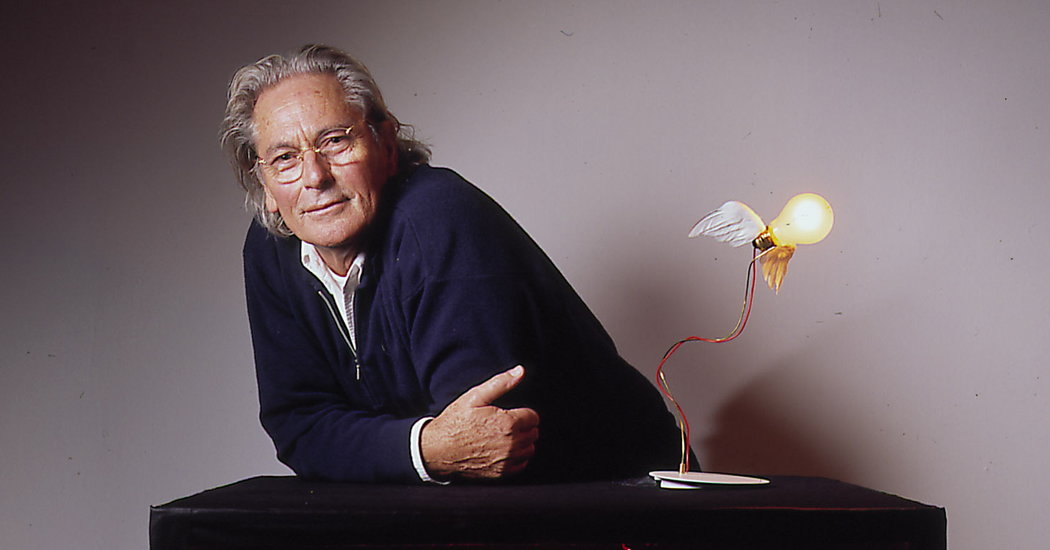

Ingo Maurer, a German lighting designer who was Promethean in his delivery of illumination — fashioning lamps out of shattered crockery, scribbled memos, holograms, tea strainers and incandescent bulbs with feathered wings — died on Monday in Munich. He was 87.

His death, at a hospital, was announced by his company, Ingo Maurer GmbH, which said the cause was complications of a surgical procedure.

Mr. Maurer had a wonky fascination with technology that took nothing away from his reputation as a poet of light, as he was often described.

His first lamp, designed in 1966, was a large crystal bulb enclosing a smaller one. Called simply “Bulb” (his product names would become more fanciful), it won praise from the designer Charles Eames and in 1968 became part of the Museum of Modern Art’s collection in New York.

For “YaYaHo,” which he made in 1984, he fashioned a lamp in the form of parallel low-voltage wires draped with shaded halogen bulbs that dangled like jewelry. In 2001 he made an early desk lamp using LEDs (“EL.E.DEE”) then later attached LEDs to wallpaper in a pattern that resembled twinkling rosettes (“Rose, Rose on the Wall”). In 2005 he embedded wafer-like organic LEDs in glass tabletops, creating starry clusters with no visible connections. In 2012, he collaborated with Moritz Waldemeyer, another German designer, to produce a narrow table lamp with 256 LEDs simulating flickering candlelight (“My New Flame”).

“He loved the technology that was coming out, but to him it was like Houdini,” said his longtime friend Kim Hastreiter, the co-founder of Paper magazine. “He used the technology in his lamps like a magic trick.”

Even so, Mr. Maurer never renounced the old-fashioned incandescent light bulb, with its golden hue and emotional power.

With “Lucellino,” he attached goose-feather wings and suspended the bulb like a hovering Cupid, and with “Wo bist du, Edison … ?” (“Where are you, Edison?”) he reinvented it as a hologram projected on a shade.

But while the materials he used for his lamps made them artful and cheeky, Mr. Maurer professed to be more interested in the medium of light itself.

“I’m very lucky to work with the material which does not exist,” he said in 2017 on a podcast produced by the design retailer Arkitektura. He couldn’t take light in his hand and bend it and look at it from different sides, he explained; light is not a thing, he said, but “the spirit which catches you inside.”

Ingo Raphael Maurer was born on May 12, 1932, to Theodor and Henny (Boeckmann) Maurer on Reichenau, an island in Lake Constance, in southern Germany near the Swiss border. His father, a fisherman and inventor, died when Ingo was 15, and his brother, the eldest of his four siblings, ordered him to leave school and find work. He could apprentice, he was told, either as a butcher or as a typographer at a local newspaper.

He chose the newspaper. Though it wasn’t an obvious career path for a lighting designer, he would later point out the lessons taught by the airy gaps between letter forms. The sparkling water of Lake Constance had also been a mesmerizing influence on him, he said.

Mr. Maurer traveled to the United States in 1960, settling in San Francisco with his German girlfriend, Dorothee Becker, and working as a graphic designer. He was there for three years, soaking up Pop Art inspirations that resurfaced throughout his career.

Returning to Munich as a newlywed, he founded a company called Design M to produce his Bulb lamp, as well as a wall storage unit called Wall-All invented by Ms. Becker. (It is currently sold by Vitra under the name Uten.Silo.) The couple divorced in the mid-1970s.

His company, now known as Ingo Maurer GmbH, eventually expanded to include 70 employees and took on all of its own manufacturing locally. It also executed ambitious civic and private commissions.

Mr. Maurer is survived by his daughters, Sarah Utermoehlen and Claude Maurer, the company’s managing director; and four grandchildren. Mr. Maurer’s second wife, Jenny Lau, died of cancer in 2014.

A handsome man with a square jaw and flowing hair that turned paper white in his last decades, Mr. Maurer had a great deal of charisma, which helped propel him through hard economic times.

“The Italians even thought he was Italian,” said Mariangela Viterbo, the head of a public relations firm in Milan, who met him in the late 1960s when he presented Bulb at a trade show in Turin. “In that period the big vision of modern design was Danish or Finnish. Ingo came with something more similar to our temperament — more ironic, more joyful. It made a difference.”

A crowning moment of disruption occurred at the 1994 Euroluce lighting fair in Milan, where Mr. Maurer introduced a chandelier made of suspended porcelain dish shards. The fixture was initially called “Zabriskie Point,” after the Michelangelo Antonioni film, which has a scene of a house exploding in slow-motion. At least one startled Italian visitor to the fair exclaimed, “Porca miseria!,” a phrase that translates roughly as “Dammit!” Mr. Maurer decided that he preferred that name for the chandelier.

Several Porca miserias! are still made, by hand, each year, but Mr. Maurer was never comfortable with the high price tag, upward of 30,000 pounds (about $38,000), as quoted by at least one website. He donated some of the profits to a family he once met in Aswan, Egypt.

Not everyone was charmed by his antic designs. Reviewing a 2007 retrospective of Mr. Maurer’s work at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in Manhattan, Ken Johnson wrote in The New York Times, “While some of his pieces are lovely to look at, his work in general is so precious and so busily eager to please that it will make you pine for the reproving austerity of the fluorescent-light Minimalist Dan Flavin.”

Paola Antonelli, the senior design curator at the Museum of Modern Art, disagreed.

“I’ve never seen anyone experiment with such abandon,” she said, “and experimentation is the opposite of wanting to please.”

Ms. Antonelli provided Mr. Maurer with a showcase in 1998, when she included his lamps in a design exhibition, and hung “Porca Miseria!” in the current MoMA exhibition called “Energy.”

She said that at one of his design events, Mr. Maurer handed out paper 3-D glasses that created a vision of little hearts when the viewer looked toward the light.

“That was so him,” she said of his whimsy. “In a pair of throwaway glasses.”