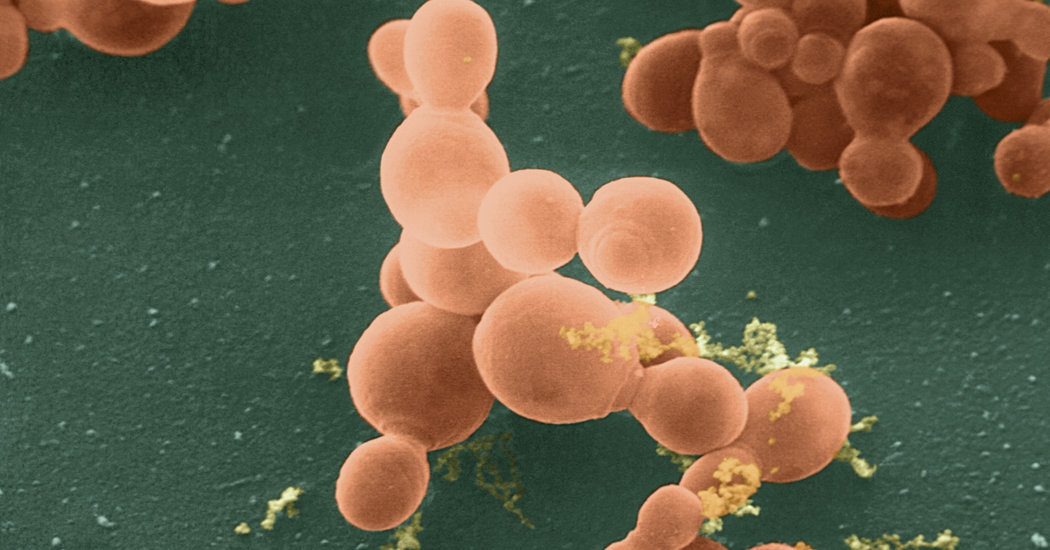

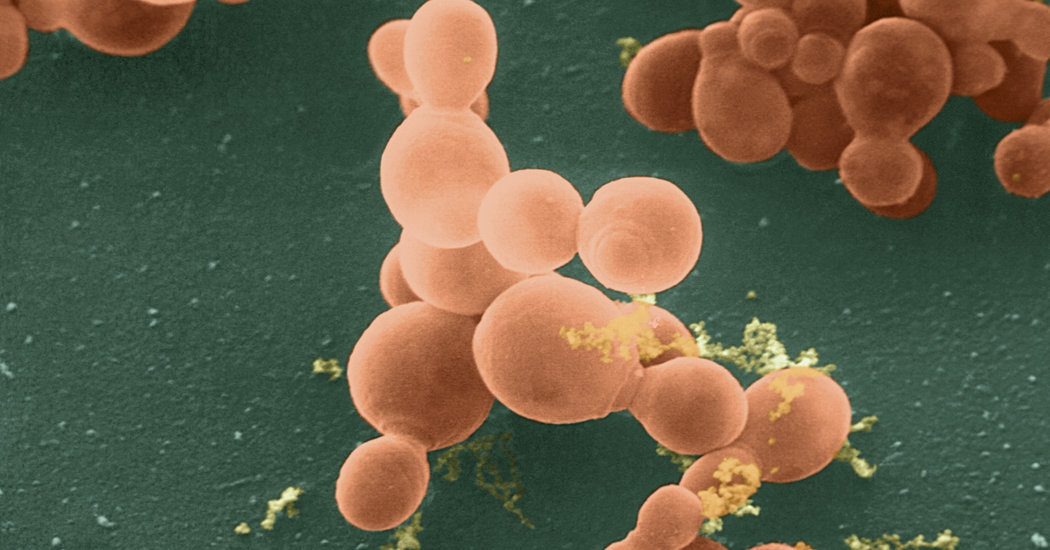

By now, you’ve probably heard that your body is teeming with bacteria. Some 100 trillion of them live on your skin, in your mouth and in the coils of your intestines. Some protect against infections and help you digest food, while others can make you seriously ill.

Fungi, viruses and protozoa call your body their home, too. Your fungal residents are less numerous than your bacteria by orders of magnitude, but as researchers are learning, these overlooked organisms play an important physiological role — and when their numbers get out of whack, they can modify your immune system and even influence the development of cancer.

A new study, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, found that fungi can make their way deep into the pancreas, which sits behind your stomach and secretes digestive enzymes into your small intestine. In mice and human patients with pancreatic cancer, the fungi proliferate 3,000-fold compared to healthy tissue — and one fungus in particular may make pancreatic tumors grow bigger.

Researchers were surprised by the presence of fungi in the typical pancreas and immense increase in their numbers in disease. “The pancreas was considered a sterile organ until a couple years ago,” said Dr. George Miller, a surgical oncologist at the New York University School of Medicine who led the study.

But recent research from Dr. Miller’s lab and others had indicated that some microorganisms, such as bacteria, could sneak past a muscle called the sphincter of Oddi, which separates the pancreas from the rest of the gut. Perhaps fungi could also colonize the pancreas the same way.

To find out, Dr. Miller and his team fed mice a species of brewer’s yeast labeled with a green fluorescent protein. The fluorescent marker revealed that the yeast had indeed moved from the digestive tract to the pancreas in a matter of minutes.

In mice, the types of fungi that ended up in the pancreas were usually very different from those that remained in the gut. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the only varieties of fungi that colonized pancreatic tissue.

One particular fungus was the most abundant in the pancreas: a genus of Basidiomycota called Malassezia, which is typically found on the skin and scalp of animals and humans, and can cause skin irritation and dandruff. A few studies have also linked the yeast to inflammatory bowel diseases, but the new finding is the first to link it to cancer.

The results show that Malassezia was not only abundant in mice that got pancreatic tumors, it was also present in extremely high numbers in samples from pancreatic cancer patients, said Dr. Berk Aykut, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Miller’s lab.

Administering an antifungal drug got rid of the fungi in mice and kept tumors from developing. And when the treated mice again received the yeast, their tumors started growing once more — an indication, Dr. Aykut said, that the fungal cells were driving the tumors’ growth. Infecting a control group of mice with different fungi did not accelerate their cancer.

There is increasing scientific consensus that the factors in a tumor’s “microenvironment” are just as important as the genetic factors driving its growth.

“We have to move from thinking about tumor cells alone to thinking of the whole neighborhood that the tumor lives in,” said Dr. Brian Wolpin, a gastrointestinal cancer researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The surrounding healthy tissue, immune cells, collagen and other fibers holding the tumor, as well as the blood vessels feeding it all help support or prevent the growth of the cancer.

Microbes are one more factor to consider in the alphabet soup of factors affecting cancer proliferation. The fungal population in the pancreas may be a good biomarker for who’s at risk for developing cancer, as well as a potential target for future treatments.

“This is an enormous opportunity for intervention and prevention, which is something we don’t really have for pancreatic cancer,” said Dr. Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue, a pancreatic cancer researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York.

Nearly 57,000 people will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the United States this year, but their prognosis will be poor. Three-fourths die within a year of diagnosis, and only about 1 in 10 live longer than five years.

“That’s because we don’t have any screening or methods of early detection for pancreatic cancer,” said Lynne Elmore, director of the translational cancer research program at the American Cancer Society.

By the time the cancer is diagnosed, surgery alone isn’t enough. Standard chemotherapies are very limited, and there aren’t any great targeted therapies, Dr. Elmore said.

The new study also sheds light on how fungi in the pancreas may drive the growth of tumors. The fungi activate an immune system protein called mannose-binding lectin, which then triggers a cascade of signals known to cause inflammation. When the researchers compromised the ability of the lectin protein to do its job, the cancer stopped progressing and the mice survived for longer.

But the interaction between microbes and their hosts is extremely complex, Dr. Miller said, and further experiments will be needed before the new findings can be applied in treating cancer patients. Microbial populations can change in response to a person’s age, diet, use of antibiotics or antifungal drugs and other factors.

“This is intriguing and exciting research,” said Dr. Ami Bhatt, who studies microbes at Stanford University. “But it’s probably too soon to add broad spectrum antifungals, many of which have lots of side effects, to cancer treatment regimens, even in experimental settings.”