To get to breakfast at Blackberry Mountain, a resort built into Tennessee’s Chilhowee Mountain, you could lace up a pair of sneakers, ideally with rugged soles, grab a walking stick, and set off on a 1.4 mile uphill climb shaded by chestnut oak trees that culminates at the Firetower, the property’s restaurant (elevation: 2,800 feet) that serves inspired riffs on traditional breakfast dishes — sunny side up eggs topped with house-fermented hot sauce and avocado yogurt — alongside panoramic views of Tennessee, Georgia and the Carolinas. On the way, you might pass candy-striped mountain laurel (don’t lick, it’s poisonous) and jet-black ravens. The trip up takes about an hour.

Or, you could call the front desk and ask for a ride in one of the in-house Lexus SUVs. On the way, you might pass golf carts. The trip up takes about five minutes (and still ends with a delicious breakfast).

This is one example of the “choose your own adventure” philosophy of vacationing advanced by Blackberry Mountain, described by its proprietor as “your own private national park.” Opened in February, it is the sister resort of Blackberry Farm, the award-winning bastion of Southern hospitality.

While the Farm, a pastoral paint by numbers with lush green lawns and white wooden rockers, is bucolic bliss, the Mountain, seven miles away in the Great Smoky Mountains, with 25 miles of private hiking and biking trails, is summer camp stepped up. Stepped way up: rates start at $995 per night (for double occupancy, including dinner and breakfast). The robust slate of activities ranges from sound bathing (a guided meditation enhanced by sonic vibrations) to endurance climbing. While the staff will graciously deliver the tools needed to make S’mores in your outdoor fireplace (they’ll even start the fire), the Mountain’s food goes well beyond the flaccid hot dogs and canned beans known to many who’ve tried to make a home away from home in the great outdoors. Up at the Firetower, mussels bathe in a Thai-spiced broth of coconut milk and ginger; down at the Lodge, the Three Sisters restaurant serves tandoori chicken atop a bed of tart cherry studded cauliflower rice.

CreditRobert Rausch for The New York Times

“It’s impossible not to eat well up here,” said Andrew Zimmern, the food and travel television show host. Mr. Zimmern was a guest at an April “house party,” a weekend of special talks, classes, and meals — Mr. Zimmern cooked up salmon that he caught in Patagonia earlier in the week — that Blackberry Mountain plans to host a few times a year to bring together the boldfaced names who’ve become part of the Blackberry family since the Farm started operating as a resort in 1976. Another one is scheduled for September, and experts in topics as diverse as combat, holistic healing, parenting and floral design are scheduled to host workshops throughout the year at the resort, nestled in the hamlet of Walland.

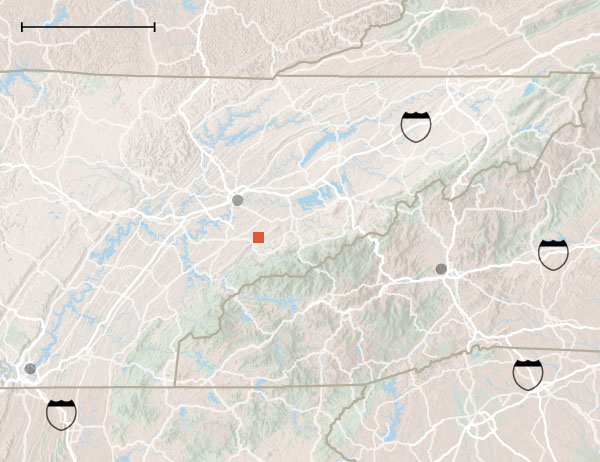

GREAT

SMOKY

MOUNTAINS

Blackberry

Mountain

NANTAHALA

NATIONAL

FOREST

Chattanooga

Street data from OpenStreetMap

North

carolina

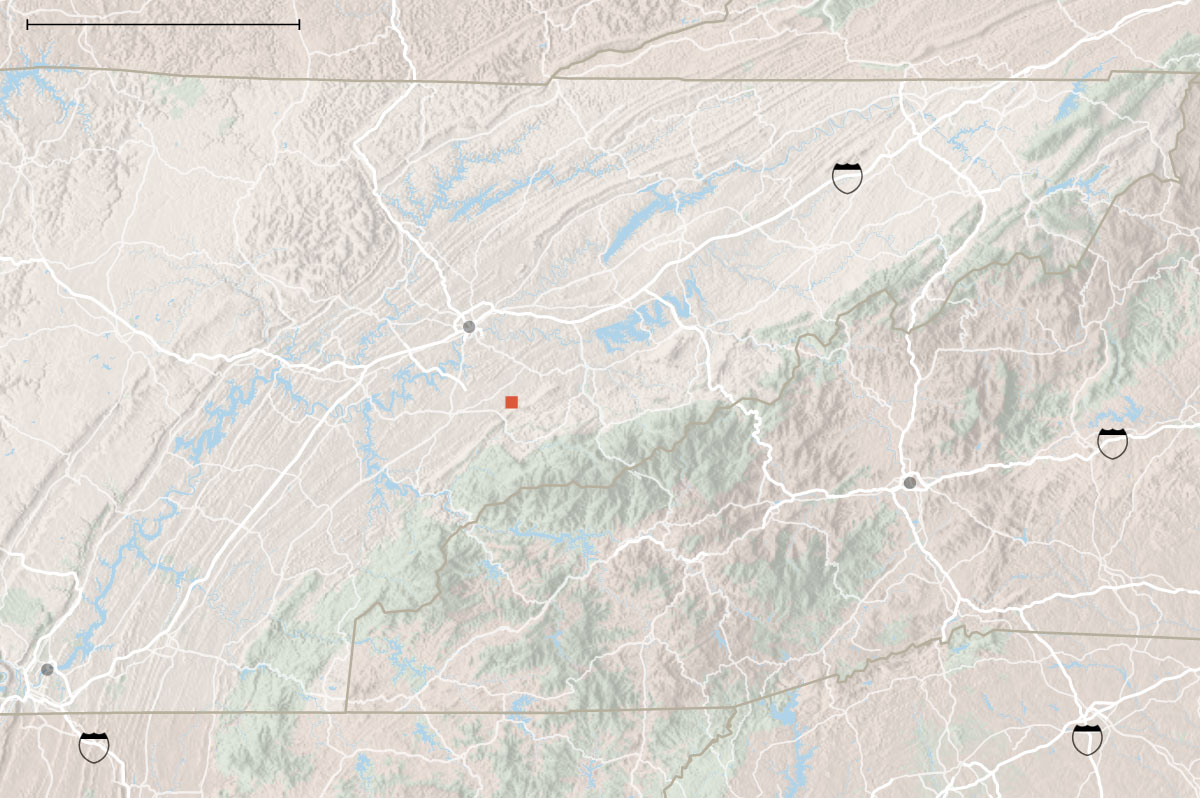

Blackberry

Mountain

GREAT

SMOKY

MOUNTAINS

NANTAHALA

NATIONAL

FOREST

Chattanooga

South carolina

Street data from OpenStreetMap

The weekend my husband and I visited, lured by the lore of Blackberry’s second-to-none food, wine and hospitality, Mr. Zimmern mingled with the winemakers Andy Erickson and Annie Favia-Erickson, who talked about their passions for yoga, hiking and tea in addition to leading a tasting of their Napa Valley Cabernets. The Nashville singer Jessie Baylin serenaded the 50 or so house party attendees in a lounge stocked with cocktails and green curry-spiced popcorn; the culinary travel consultant Christina Grdovic moderated a fireside chat with Mr. Zimmern, in which he shared a Buddhist proverb, told to him by the Dalai Lama, that helped him come to terms with his past substance abuse.

“These are smaller gatherings, it’s a smaller property than the Farm, and we can have really intentional conversations,” said Mary Celeste Beall, the proprietor of Blackberry Farm and Mountain. “Our goal is to find people who have interesting roles in society and say, ‘Share your knowledge with us, but also share your passion in something that’s completely different.’”

This is how I ended up shooting clay pigeons next to Mr. Zimmern, though he required less help than I, a firearms novice taken under the wing of a very kind instructor named Caleb, who smiled and told me to “just shoot when I say ‘bang.’” The next day I shifted gears, attending a restorative yoga class with Ms. Favia-Erickson. We held pigeon poses and supine twists for long, languid stretches; an instructor with svelte arms and a soothing voice weighted down our limbs with strategically placed sandbags and described the class as “a guided nap.” “You can’t add wellness to your body,” Ms. Favia-Erickson said afterward, as she brewed a pot of her Napa-grown lemon verbena tea for the group. “You have to do it from the inside out.”

“Wellness” has become a buzzword in travel, applied to hotels, resorts and retreats. Blackberry Mountain lets guests decide what wellness means to them. “Some people might want to do three classes every morning and hike to lunch,” Ms. Beall said. “Some people might do one. I can’t wait until I have time to exercise all day long for three days, to not drink and feel so clean and amazing, but I also love the more balanced, realistic idea of, ‘Let’s get some exercise done in the morning, I’m going to eat a great lunch, I might have a glass of wine in the afternoon, and then I might do a cocktail clinic.’ It’s a mix. People can take it for what they want.”

While Blackberry Farm includes breakfast, lunch and dinner in its daily room rate, the Mountain’s includes breakfast, dinner and most classes (alcohol, at both resorts, is charged by consumption). This, according to Hall Mebane, one of the 21 fitness and outdoor adventure guides employed by the Mountain (he specializes in rock climbing) is what sets the two resorts apart.

“When we say ‘wellness,’ we mean mental and physical wellness,” he said. “Everything on the Mountain is meant to get you into a state of well-mindedness. Food at our restaurants is healthier, it’s meant to be fuel for you to re-engage in activity,” which need not mean breaking a sweat (although the state of the art fitness center and curious class offerings like cardio drumming and suspension Pilates make a good case for doing so). One of Ms. Beall’s priorities, in developing the Mountain, was to build an artist’s studio — her mother is an artist and never minded paint on anyone’s clothes. The Mountain offers classes in disciplines like painting, basket making and hand-thrown pottery.

“That’s part of wellness: taking time away from our devices to use the other side of our brain to engage in creating something,” said Ms. Beall. (The popularity of the pottery class may have had unintended side effects. During the April house party, a guest passed around a phone showing an Instagram post of the glossy, artfully imperfect bowls a friend made during a recent stay: “Look how cool they turned out, and they’ll pack and ship them home for you, too!”)

A decade ago, Ms. Beall, 42, and her husband, Sam Beall, purchased 5,200 acres of woods that they could see from the veranda of the Farm’s main house, wary of someone else scooping up the land and developing it to oblivion. They put 2,800 acres in conservation and had a few renderings made. “Sam had seen every inch of the mountain and knew it so well,” Ms. Beall said. “He’d take a four-wheeler up there and just go. I had been there a lot but I am not the adventurer he was.”

In 2001, Mr. Beall, a Culinary Institute of America-trained chef, took over management of Blackberry Farm from his parents, Kreis and Samuel E. Beall III (the elder Mr. Beall is the founder of the Ruby Tuesday chain of restaurants). Having attracted world-renowned chefs and the foodies who follow them to the Farm, with the Mountain, he and Ms. Beall sought to create a similar kind of haven for wilderness lovers. She never imagined doing it without him, but after Mr. Beall died in 2016, at age 39, following a skiing accident, Ms. Beall, a mother of five, felt compelled to see her husband’s vision through.

“I joke, but not really, that if I hadn’t had to get up and get dressed and go to a meeting about Blackberry Mountain, I don’t know what would have happened to me,” she said. “Figuring out the layout, the restaurants, the activities — it was a way for our whole team to honor Sam but also to say, ‘This is such a crazy idea, Sam would’ve loved it.’”

That’s how the 1.4 mile hike to breakfast came to be. Intrepid guests staying in the six Watchman cabins by the Firetower can kick off their stay with this uphill climb, though they’d do best to let an SUV transport their luggage. Most of the property’s 22 other cottages and multi-bedroom homes are within striking distance of the Lodge, and can be reached in a few minutes by foot or golf cart, which are swifter and quieter than standard models (they don’t beep when backing up, so as not to disrupt any quests for mental wellness).

Other parts of the property reflect Ms. Beall’s eye for design and knack for anticipating what guests want. While the Farm’s style of décor is Southern Plantation home meets French country estate, with worn wood, heavy drapes, and leather bound classics lining the shelves, the Mountain’s is decidedly more modern. Grays and blues instead of maroons and golds. “The Marine Corps Way to Win on Wall Street” instead of “The Essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson.” Organic Himalayan pink sea salt popcorn in the complimentary mini bar instead of potato chips and pimento dip. A room at the Farm might include one of Mr. Beall’s hardcover cookbooks; at the Mountain, every room comes with a pocket-size guide to flora, fauna, and “how to enjoy the mountain.” (“Step 1: set your intention.”)

Some design touches from the Farm translated to the Mountain, like the heated floors in the bathroom and the framed painting that hides the television — it’s on a pulley weighed down by a hunk of Tennessee field stone, a trick Ms. Beall learned from her mother-in-law. “Sometimes, during the planning of this place, I’d be the only woman in a room full of men, with all of them going, ‘But where’s the TV going to go?’” she said, rolling her eyes.

In Ms. Beall’s ideal world, the painting wouldn’t move. The idea is for guests to spend less time watching television in their rooms and more time out on the mountain, mingling with their fellow campers, building connections that will last after they leave. Two of mine have: Ms. Favia-Erickson, an Indian food fanatic, happened to be in Los Angeles, where I live, in late April and joined my husband and I for a home-cooked Indian meal (made, I confess, by my mother-in-law).

And while exactly none of Mr. Zimmern’s clay pigeon shooting skills rubbed off on me, we bonded over something else: the sauce that he put on top of his Patagonia-caught salmon at dinner on Saturday night, a piquant, mouth-numbing flurry of flavors so memorable, I had to ask him what it was. A week later, I had a bottle of his Minneapolis restaurant’s Sichuan peppercorn-flecked Mala sauce on my doorstep. (It’s being carefully rationed.)

“When you connect people with a common interest, it’s magical,” Ms. Beall said. “That’s our goal with the Mountain: how can we create more magic for our guests?” Hiking not necessarily required.

Sheila Marikar, a writer based in Los Angeles, is at work on her first novel.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.