Faced with a lethal Ebola outbreak threatening eastern Africa, public health officials are conceding that their battle plan is failing and have proposed a comprehensive new strategy for containing the virus.

It envisions reframing the epidemic as a regional humanitarian crisis, not simply a health emergency. That may include more troops or police to quell the murders and arson that have made medical work difficult, as well as food aid to win over skeptical locals.

The Democratic Republic of Congo also plans to deploy a second vaccine to form a protective “curtain” of immunity around outbreak areas.

The outbreak, which began a year ago in Congo and was declared a global health emergency this month, is now the second-biggest in history, with more than 2,600 cases and more than 1,750 dead. It has persisted in part because of a fierce but hidden power struggle within Congo’s government for control of the response, according to documents obtained by The New York Times and interviews with Ebola experts.

The country’s health minister, Dr. Oly Ilunga, resigned on Monday after a public dispute with donors at a meeting in Geneva over whether to roll out the second vaccine, which he opposed. The containment effort will no longer be overseen by the health ministry but by an expert committee reporting directly to Congo’s new president, Felix Tshisekedi.

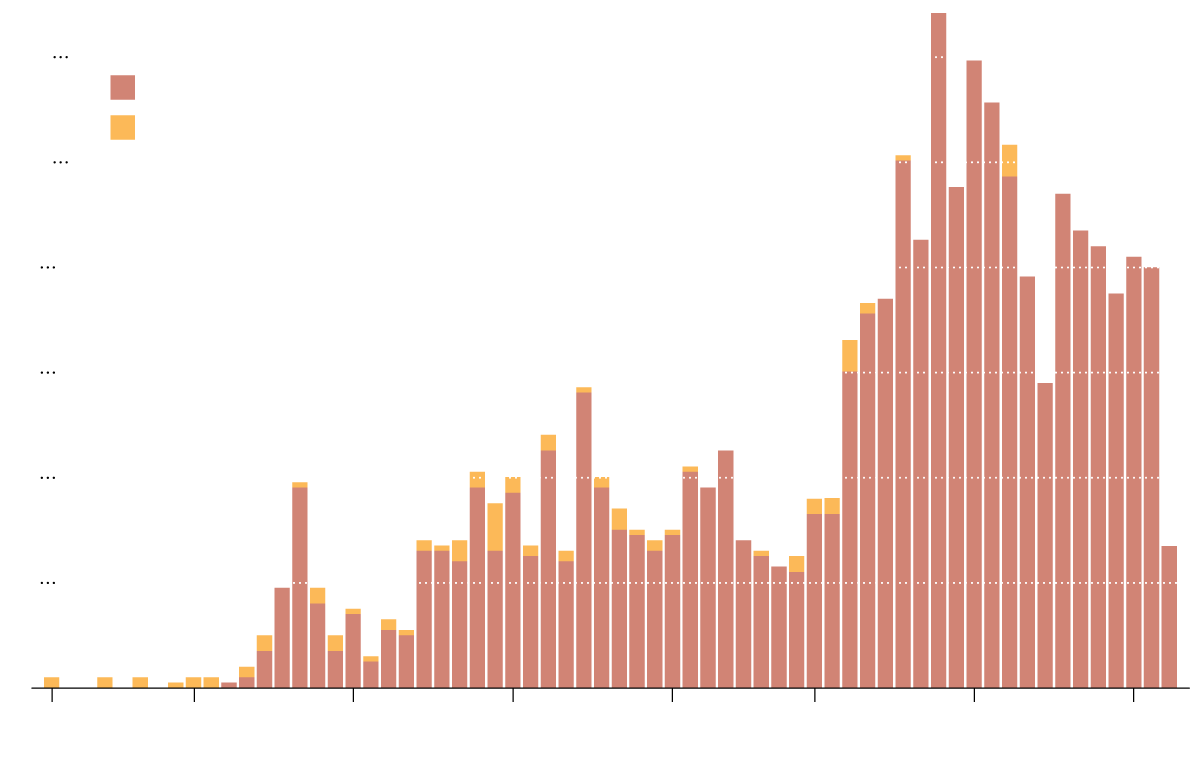

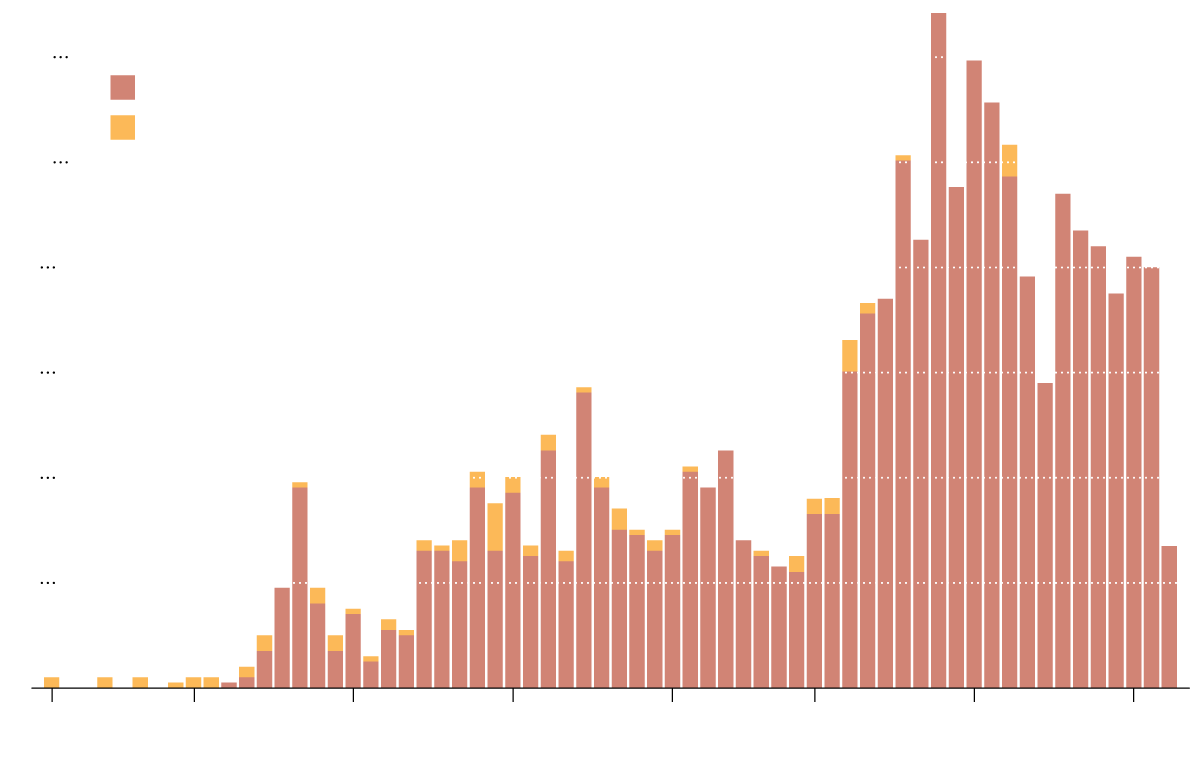

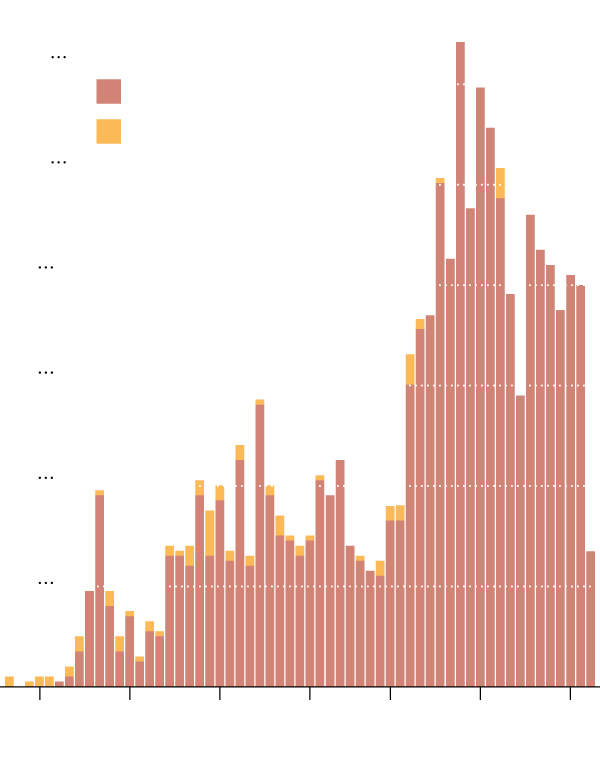

Ebola Cases by Week

Reported cases in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as of July 21.

Confirmed cases

Probable cases

Confirmed cases

Probable cases

Dr. Ilunga was the target of a scathing internal government report produced in April, just as new cases began soaring above 100 per week. The report was written by a commission convened by Congo’s new president, some of whose members are now overseeing the response.

The report said “arrogant” national health officials took “an aggressive and ostentatious attitude” when they visited the outbreak area, renting deluxe hotel rooms and expensive cars and “brandishing large dollar bills” while local health workers went unpaid.

A spokeswoman for Dr. Ilunga called the report “weak.” She said he had resigned not because of it, but because the president had split the authority to oversee the response between his office and an independent commission, which she claimed was a violation of the Congolese Constitution.

CreditJohn Wessels/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Dr. Ilunga’s departure pleased some donors and agencies supporting the fight against Ebola. The United States is by far the biggest donor. Tibor P. Nagy, the State Department’s top official for African affairs, told a Senate subcommittee on Wednesday that Dr. Ilunga’s resignation “may be an improvement to the situation.”

The country is seeking $288 million to implement its new Ebola strategy, and is likely to get it. The World Bank recently offered $300 million. The United States increased its previous giving by $38 million this week, and federal aid officials have said they are committed to containing the outbreak at its source.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

The new plan may include a campaign to win the hearts of the traumatized population in the isolated eastern provinces by immunizing them against other diseases, treating children for parasites, handing out food and even creating thousands of jobs. Experts hope efforts will be made to negotiate a truce with local militias.

The health ministry’s strategic plan for the period from July to December, written in cooperation with the W.H.O., has not been officially released but is circulating among the donors and health agencies, and a copy was obtained by The Times. While it envisions a much broader response, the plan is vague on specifics — omitting even references to which vaccines should be used.

By contrast, the commission’s report in April endorsed the second vaccine by name and called for many specific actions, like giving hot meals to malnourished children. Because its main authors are now leading the response, experts expect those steps will be taken.

SOUTH

SUDAN

Current

outbreak

DEM. REP.

OF CONGO

CONGO

REP.

Forested areas

Areas at risk of

Ebola outbreaks

SOUTH

SUDAN

Current

outbreak

DEM. REP.

OF CONGO

Forested areas

Areas at risk of

Ebola outbreaks

Even though the W.H.O. and many donors endorsed the new vaccine, made by Johnson & Johnson, in May, Dr. Ilunga vigorously opposed using it. He said it would confuse the populace and be difficult to administer, since it requires two doses given 56 days apart.

To avoid confusion, it will be deployed differently from the current single-dose Merck vaccine. While that one is used to “ring-vaccinate” everyone around each known case, the new vaccine will be used in areas further away to encircle the hot zones with immunized people.

For example, while the Merck vaccine has been given to Ugandan health workers on the Congo border, the new one will be deployed in Mbarara, a regional capital 60 miles away with a big hospital that ill patients might travel to.

Close to 200,000 doses of the Merck vaccine have been distributed. The company has plans to produce 800,000, but some experts fear shortages, especially if the virus escapes into South Sudan, which is as dysfunctional and war-torn as eastern Congo.

Johnson & Johnson has offered 500,000 doses; the vaccine is easier to store and has been tested for safety on 6,000 human volunteers, but has not been deployed in the field.

At its core, the political struggle within Congo pitted Dr. Ilunga, 59, who had been a minister since 2016, against Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe, director-general of the country’s National Institute for Biomedical Research.

It also was a struggle between President Tshisekedi and his predecessor, Joseph Kabila, 48. After 18 contentious years in office, Mr. Kabila stepped down last year and is now a senator for life. In December, Mr. Tshisekedi won a disputed election, beating Mr. Kabila’s chosen successor. But since then, he has only slowly replaced Mr. Kabila’s cabinet ministers.

Dr. Ilunga, who visited the outbreak area several times, is respected by some Ebola experts. The head of one international agency, speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid involvement in another country’s dispute, called him “principled and data-driven.”

Dr. Muyembe, 77, is an internationally respected authority on Ebola who has helped fight every outbreak since the virus was discovered in 1976, when the country was named Zaire.

The report by the commission led by Dr. Muyembe accused Dr. Ilunga of “weak governance, weak leadership and a hyper-centralized response” that failed to coordinate with other ministries, including the police and army.

In addition to accusing Dr. Ilunga and his staff of arrogance and ostentation, the report also cataloged serious medical failures.

People with fevers who entered screening centers to see if they had Ebola did not get test results for three to five days, by which time they might become infected with Ebola — or infect others if they had it. Private clinics and traditional healers held patients in order to make money,

Little was done to protect areas where the virus had not yet appeared or to coordinate with neighboring countries, the report said. And while the commission’s field visits had gone “generally well,” its work was hampered because Dr. Ilunga had refused repeated requests to meet with members and his office had been uncooperative with information requests.

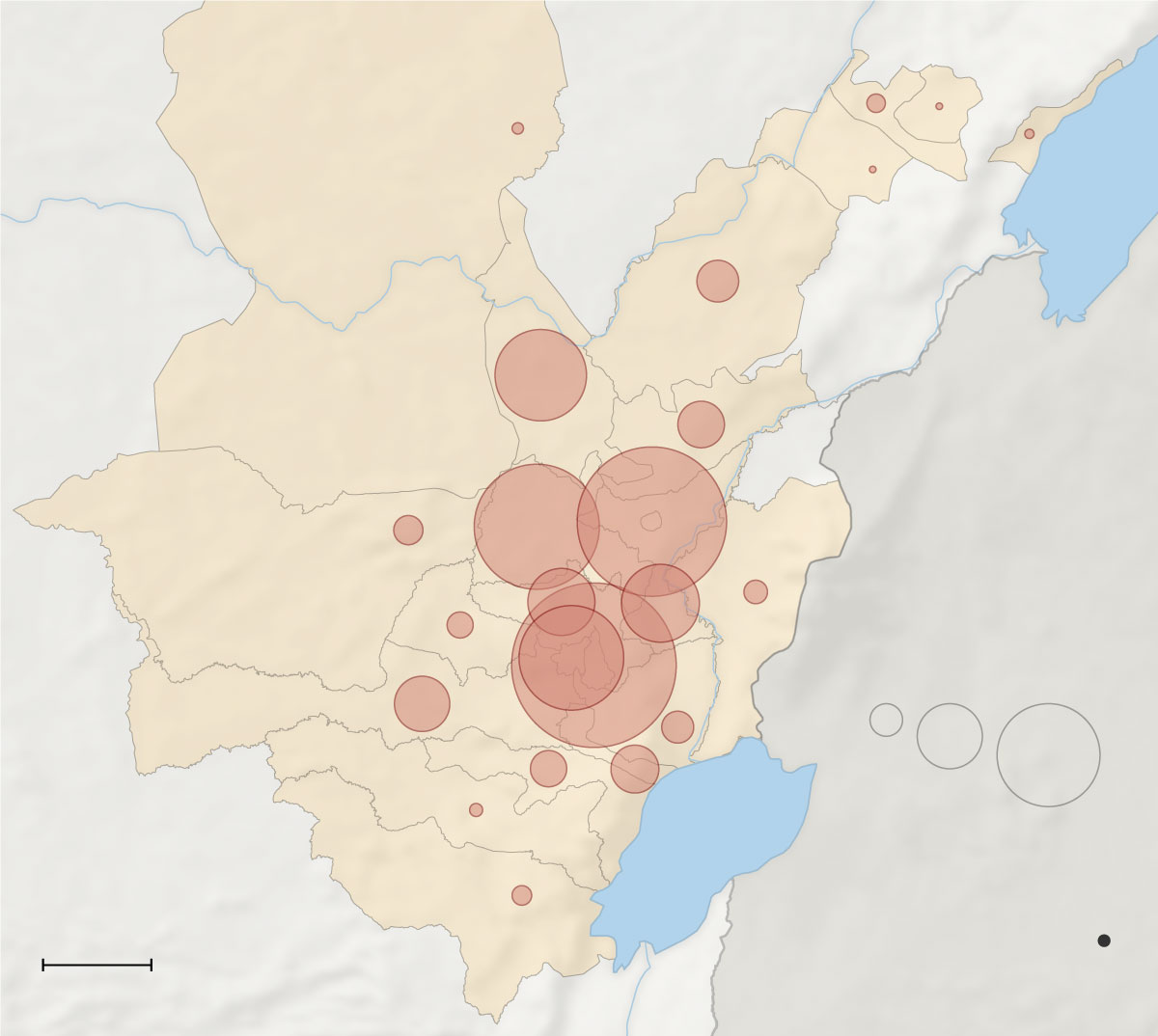

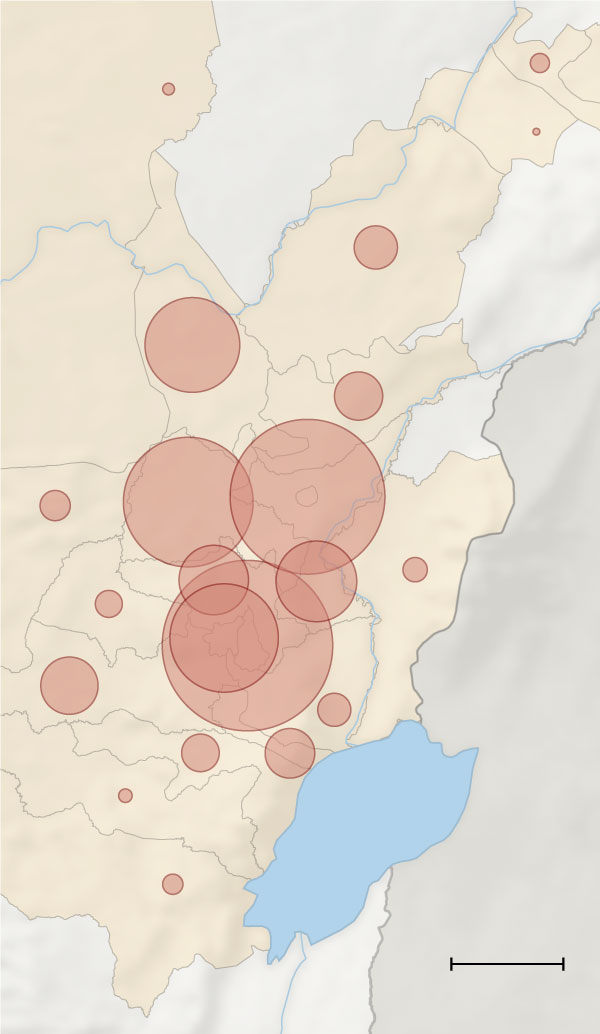

Affected Areas

Reported cases by health zone, as of July 21.

LAKE

ALBERT

DEM. REP.

OF CONGO

NUMBER OF CASES

LAKE

EDWARD

DEM. REP.

OF CONGO

LAKE

EDWARD

Jessica Ilunga, a spokeswoman for the former health minister, derided the report and said it “had no data” — such as the names of health workers who claimed they had gone unpaid.

She denied that national officials had spent too much money and scoffed at the idea that outbreak cities like Butembo even had luxury hotels. National officials had needed running water and internet connections to do their jobs, she said, while some had even slept in tents.

The ministry did cooperate with neighboring countries, she said, pointing to efforts with Ugandan officials when the virus briefly crossed the border.

In her view, the commission had failed to contact the ministry, even after being asked to explain what it was investigating. Also, she said, its members had met separately with outside agencies and had tried to countermand ministry orders to its front-line workers.

In addition, she said, since he took office in January, Mr. Tshisekedi had refused to see Dr. Ilunga.

The tense atmosphere was fostered by rivalry between the current president and the former one, said Dr. Peter Piot, director-general of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

But, added Dr. Piot, who is a discoverer of the Ebola virus and serves on W.H.O. advisory committees, there also appeared to be personal antagonism between the two doctors.

In late spring, he said, when he and Dr. Muyembe went to Dr. Ilunga’s office to discuss the second vaccine. Dr. Ilunga — “appearing quite autocratic,” he said — agreed to see him but refused to admit Dr. Muyembe.

“I thought, ‘Oh, God. I didn’t realize how bad the dynamics were.’”

Denise Grady contributed reporting.