CHICAGO — Because photographs record a moment that has passed, they are by nature poignant. But a particularly bittersweet mood infuses an ambitious exhibition here of photographs, paintings and videos of L.G.B.T.Q. art. The show, titled “About Face: Stonewall, Revolt and New Queer Art,” through Aug. 10 at the Wrightwood 659 art exhibition space, is the most unconventional of the Stonewall anniversary shows. It is made up of mini-retrospectives of artists who are, for the most part, underrecognized. Some were lost to AIDS in the ’80s and ’90s. A number of those spared by the virus have coped with alcohol and drug addiction.

When well-known artists are included, as with Peter Hujar, Greer Lankton and Roger Brown, they are represented by many unfamiliar pieces. And in the case of Harvey Milk, who is probably the most famous name of all, we see evidence of an overlooked amateur photography career that would probably merit little attention had Milk, the proprietor of a now legendary camera shop in the Castro district, not become a trailblazing San Francisco politician. Still, Milk’s photographic legacy is creditable, and, in light of his murder, haunting. (The show is curated by Jonathan D. Katz, a scholar specializing in L.G.B.T.Q. art.)

The upbeat works in the show were usually made by lesbians, including Joan E. Biren, Alice O’Malley and Sophia Wallace, who in very different ways celebrate female sexuality and lesbian pride, and by a few younger artists who came along late enough to escape the ravages of the epidemic.

In an exhibition that includes nearly 500 pieces by 39 artists, mostly represented in depth, these are five of the most intriguing.

A Window on Baltimore’s Hidden World

Creditvia Wrightwood 659

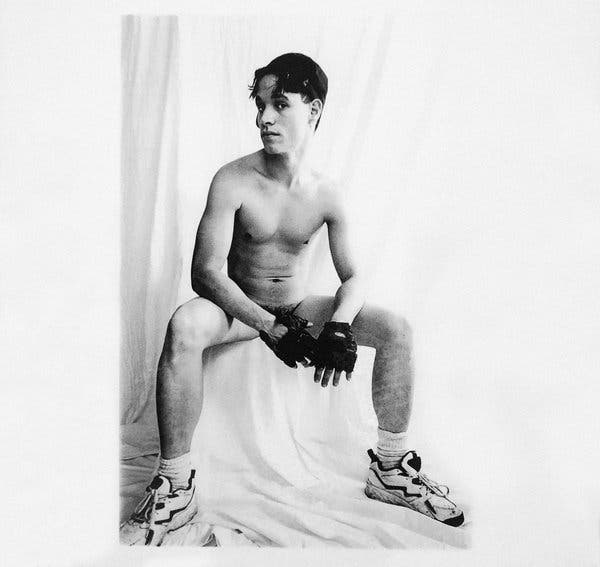

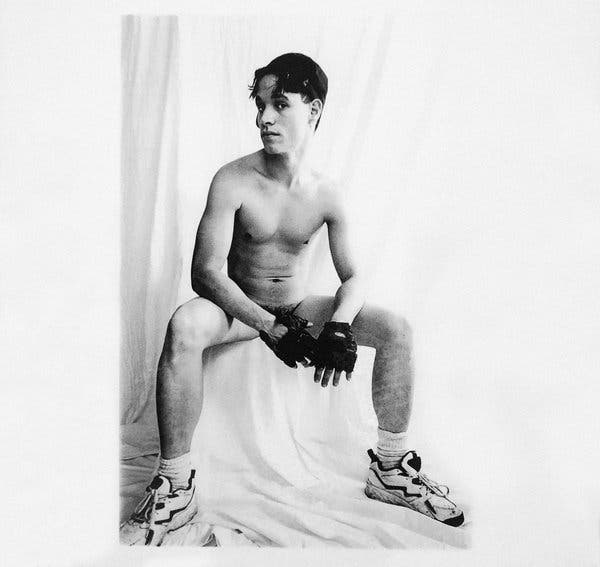

Amos Badertscher, 82, has devoted his career, and life, to recording the hidden world of young men in his Baltimore neighborhood — castoff youths who turn tricks to finance their drug and alcohol habits but usually don’t regard themselves as gay. Mr. Badertscher, who benefited from a small inheritance, taught himself to photograph and turned his obsession into a documentary project. He quickly abandoned his early romanticism for sharp-focused portraits of individuals. On many of the prints, he writes in the margin about the person: what brought him to this point and, because Mr. Badertscher maintains contact with many of his subjects for years, what happened after the picture was taken. Too often they died young. Adding tension to his photographs is the problematic power dynamic in these transactions: Mr. Badertscher often includes his own figure, reflected in a mirror as he photographs his hard-pressed subjects.

Laughing at the Apocalypse

The 117 mixed-media artworks by Jerome Caja constitute the largest display of his work since he died of AIDS in 1995 at the age of 37. And they are a revelation. With biting humor and Rabelaisian earthiness, Mr. Caja conveys the horrific absurdity of the AIDS epidemic as it was experienced by young gay men. The sexual liberty they embraced as life-affirming had marked them, seemingly at random, for hideous deaths. What else could he do but joke about it?

One of 11 sons raised in a Roman Catholic family in Cleveland, Mr. Caja found himself in San Francisco, where he studied art and established a reputation as an outrageous drag queen. His small-scale art works often invoke Catholic imagery and can suggest reliquaries. Mr. Caja developed a personal iconography, featuring birds, eggs, bunnies, pigs, blond Venuses, and more. His portraits are usually self-portraits, with his telltale large nose and full mouth. He painted with nail polish, mascara, whiteout, glitter and other trashy materials. And his supports were similarly humble: restaurant tip trays, scraps of wood, paper doilies, cheap frames with the price sticker still attached, bottle caps, even pistachio shells.

It would be understandable for an afflicted artist to portray the trials of AIDS as an ongoing agony — in the Greek sense of the word, a contest or struggle. Richard Hofmann, another painter lost to AIDS who is included in the show, depicted the onslaught of the disease that way, with Neo-Expressionist swirling figures who are heroic even when crucified.

By contrast, Mr. Caja’s “Carrot Pieta” portrays a pink bunny holding a carrot with a human face and showing it to a grieving chicken; a small cross is visible in the background landscape. In an untitled work, he takes a sacred-heart plaster statue of Jesus and replaces the heart and the halo with skulls, and the compassionate face with the head of a clown.

Clowns recur frequently in Mr. Caja’s work, as do skeletons. Sometimes they are copulating with macabre glee. At other times, the clowns are mournful. In “Death of a Bozo,” two clowns hug the body of a third; the hair of all three is in flames.

But perhaps Mr. Caja’s most effective alter egos are avian. He was partial to sunny-side up fried eggs, which, despite being cooked, sport a cheery name and a resemblance to smiley faces. In “Eggs Having Turkey Dinner,” eight eggs seated on egg cups surround a roast turkey on the table, except for one fried egg, with birdlike features, that spilled onto the floor.

One of the funniest works doesn’t address AIDS, at least not directly. “Expectant Mother Smoking” shows a black bird hovering over a nest with four eggs while smoking a cigarette.

The artist prettifies nothing. After a close friend, the artist Charles Sexton, died of AIDS, Mr. Caja combined his ashes with nail polish and other colors, to paint portraits as mementos for mourning friends.

Mr. Caja’s gallows-humorous response to AIDS resonates with that of the fiction writer David B. Feinberg. (He, too, died at 37.) Mr. Caja has never had an exhibition in New York. This impressive selection, which Mr. Katz curated with Anthony Cianciolo, makes a compelling case for one — ideally to be installed, as here, in a clutter of exuberant overload.

Religious Monsters

Educated in London, Tianzhuo Chen, 34, lives in his native China, dividing his time between Beijing and Shanghai. Working with performance and video, he flamboyantly amalgamates elements of rave parties, Butoh dance and Asian religions to produce hypnotically weird optics.

He has two videos in the exhibition. (Placed opposite each other, the installation muddles the two soundtracks.) “Light Luxury,” a collaboration with the trance electronic musician Aïsha Devi, is set in a spa outside Shanghai. The bubbling thermal water is occupied by overfed, overprivileged naked Chinese men (and Ms. Devi). Suddenly, from beneath the surface, a pink-skinned, orange-haired monster appears, succeeded soon afterward by another creature, with striped arms, an orchid on its head, and a barracuda dangling from its fishlike mouth. Except for Ms. Devi, no one notices.

In “G.H.O.S.T.,” set in the holy Hindu city of Varanasi, another plump Chinese man, with dyed blond hair and reddened skin, is floating on a boat in the Ganges. He is joined by a man outfitted to resemble a Tibetan Buddhist demon, bearing a ring of white cowrie shells around his mouth, plus two shells, painted like eyes, below his real eyes, which remain closed as he performs his undulating, erotic dance. In these surroundings, where corpses are placed on funeral pyres at the riverside ghats, “G.H.O.S.T.” addresses transcendence, sexuality and death in an original way that seems both very new and very old.

An Intimate Circle of Friends

Part of the “Boston School,” a group of art students in that city in the ’80s that included Nan Goldin, David Armstrong and Mark Morrisroe, Gail Thacker, 60, has attracted less attention than her peers.

Confronted with the AIDS diagnoses of her friends, she contrived a way of representing their deterioration. Using Polaroid film bequeathed by Morrisroe she wrapped the unrinsed negatives in plastic for years before printing, and allowed the images to blister, congeal and corrode over time.

It’s an elegant conceit, and powerful in its way. But the most memorable of her photographs in this exhibition is the undoctored portrait of Morrisroe half-buried in the blankets of his hospital bed, looking defiant and lost.

Not Either/Or, but Both or Neither.

Born intersex, with both male and female characteristics, Del LaGrace Volcano knows from the inside that gender expression is a performance. Living with a queer husband and their two children in a Swedish village, Volcano, who was raised in California and is 62, has made a career photographing subjects who also reject the traditional gender binary.

“Dred King Club Casanova, NYC,” from 2000, portrays a black drag king who strikes a cocky male attitude and is wearing, along with a big Afro wig and applied chin whiskers, an open shirt that reveals breasts; while “David Schneider FTM, Berlin” (1997), depicts a bare-chested female-to-male transsexual, as androgynously beautiful as Jean Seberg in “Breathless,” attired in a leather harness and holding a whip.

What is real and what is a pose? Looking at Volcano’s portraits, you realize the dubiousness of such distinctions.

About Face: Stonewall, Revolt and New Queer Art

Through Aug. 10, Wrightwood 659, 659 West Wrightwood Avenue, Chicago; 773-437-6601; info@wrightwood659.org.