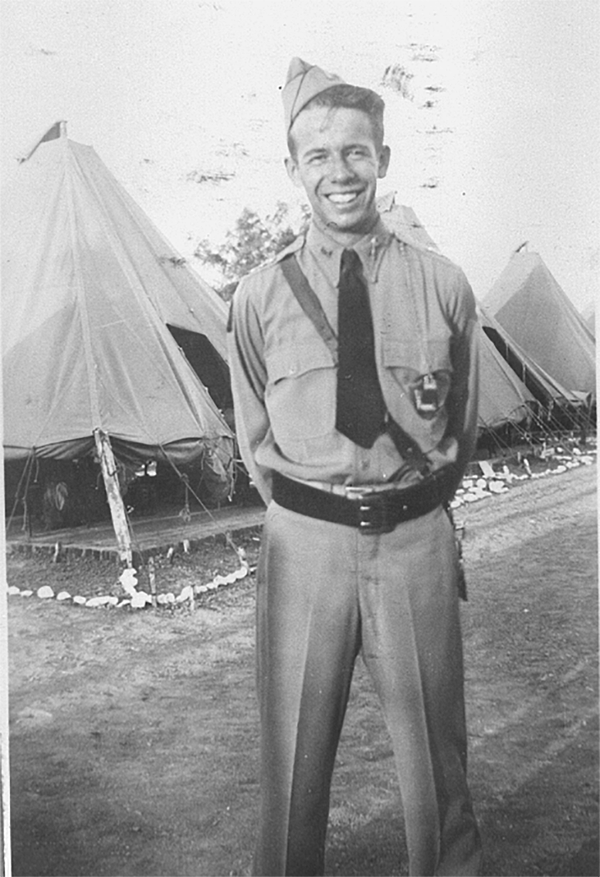

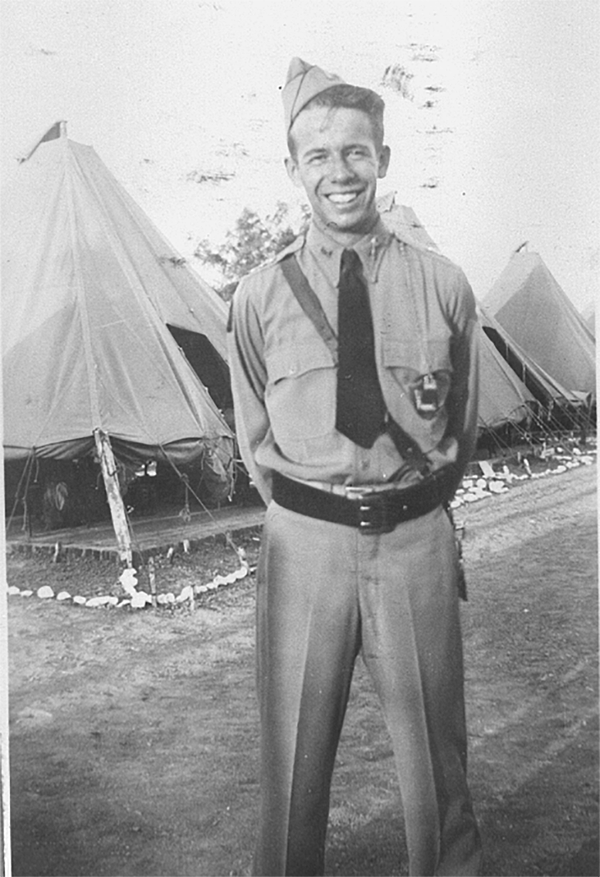

When my grandfather Michael Linehan Jr. arrived in North Africa in December 1943 to begin his tour of duty with the 15th Air Force, the average life expectancy of an Allied heavy-bomber crewman was roughly six combat missions, less than a fourth of what he was required to fly. As the 25-year-old pilot of a B-24 Liberator, my grandfather flew in some of the most decisive engagements of the war, including the Battle of Anzio and the second Ploesti oil-field raids. Upon completing his tour, he was transferred to the Eighth Air Force just in time to fly bombing runs on D-Day. According to his discharge papers, he earned a Distinguished Flying Cross and two Air Medals before being sent to Texas in August 1944. He spent the remainder of the war training new bomber pilots near El Paso, a job he liked to joke was scarier than combat and in reality was hardly less dangerous. Driving through the area with my uncle several years later, he pointed to a mountain looming over the edge of town. “See all those craters?” he said. “Those were made by new guys.”

My grandfather stopped talking about the war long before I was born, and very few of his stories survive. One is of a low-flying mission over Crete, during which half his squadron was gunned down by German antiaircraft batteries. B-24 crew members had such a high fatality rate during World War II that the aircraft was nicknamed “the flying coffin.” Between the Luftwaffe and the German 88s, there was only so much a crew could do to avoid being blown out of the sky. More than 52,000 American airmen were killed in the war. For many of those who made it home, existential questions over the role luck played in their survival would eventually take a heavy toll on them and their families. “The flyer who returns to his home and is lionized for heroic exploits may still torture himself with the feeling of unworthiness and guilt,” the sociologist Willard Waller cautioned in his landmark 1944 book, “The Veteran Comes Back.”

My grandfather’s brother, Jack, served with the Navy in the Pacific, and after the war the two men bought adjacent homes in their native Dallas, where their father emigrated from County Cork, Ireland, as a teenager. The brothers also started a plastics-manufacturing company, and it became lucrative enough to support their mutual devotion to gambling, liquor and bird hunting. My grandfather was a lifelong driver of big Cadillacs, and he liked to drive the way he flew his B-24: fast and loaded on bourbon. I never really got to know the man, in part because laryngeal cancer deprived him of a voice box in his later years. The last time I saw him, he was on his deathbed, enmeshed in medical tubing and fighting for oxygen.

He died in May 2005. A man he flew with in the war attended the funeral. After the ceremony, he introduced himself to the bereaved as a member of the Lucky Bastard Club. My grandfather had also belonged to the group. The club was exclusive to Allied bomber crewmen in Europe, but it wasn’t much of an organization. The perks of membership were small, like getting to cut in line at the chow hall. To be inducted, an Allied airman had to complete a full tour of duty. That was the only criterion. “On this 5th day of July, nineteen hundred and forty four, the fickle finger of Fate has traced on the rolls of the Lucky Bastard Club the name of Michael Linehan Jr.,” states the certificate my grandfather kept on a shelf to remind him that he had “achieved the remarkable record of having sallied forth, and returned, no fewer than 50 times, bearing tons and tons of high explosive Goodwill to the Feuhrer and would-be Feuhrers.”

[Sign up for the weekly At War newsletter to receive stories about duty, conflict and consequence.]

I grew up thinking of my grandfather as a drunk. His spiral into self-destruction left a legacy of bitterness and addiction that will haunt our family for generations to come. But only recently have I begun to realize how much of that legacy is rooted in the war. My grandfather came home with a piece of paper essentially stating that he didn’t earn or deserve the rest of his life. That’s pretty much how he lived it. And, without conscious intent, that’s pretty much how I lived, too. In 2006, I dropped out of college and joined the Army, in-processing at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, where my grandfather had out-processed six decades before. Not that he inspired me to enlist; to the contrary, I thought war might purge some of the Linehan from my blood — specifically, the lack of confidence and the self-destructive tendencies that had hobbled me since I was young. I wanted to sever ties with the Lucky Bastard Club. Instead, I became a member.

In May 1944, a pair of psychiatrists with the U.S. Army Air Forces Medical Corps, Lt. Col. Roy R. Grinker and Maj. John P. Spiegel, presented a paper on the mental-health status of returning airmen to the American Psychiatric Association (A.P.A.) in Philadelphia. They reported that “one of the most amazing revelations derived” from their clinical work was “the universality of guilt reactions,” which were “related to the most varied, irrational and illogical experiences.” They continued: “Hundreds of little acts which the patient did or did not do are the bases of self-accusations, and we often hear the guilty cry, ‘I should have got it instead of him!’ The intensity of these guilt feelings is proportional to the severity of the inner conflicts.”

Grinker and Spiegel were describing the phenomenon generally known as “survivor guilt,” which has been defined by the A.P.A. as “guilt about surviving when others have not, or guilt about behavior required for survival.” In the decades since, psychologists have found survivor guilt to be very prevalent across a wide range of traumatized populations, from Holocaust and Hiroshima survivors to refugees and H.I.V.-negative gay men. How the condition manifests depends on myriad factors, such as the nature of the trauma and the survivor’s personal circumstances. Some people’s experience of it may include workaholism, alcoholism or drug addiction, but the underlying struggle is a deep sense of despair. “Often, the survivor works hard in business relationships, but does not enjoy the work or its product because of ongoing feelings of unworthiness and impending doom,” states the “Encyclopedia of Death and the Human Experience.” “There can be a sense that the only answer to the internal pain is personal death, a resolution to the issue of having survived the original event.”

Clinical studies found survivor guilt to be so pervasive among Vietnam veterans that the A.P.A. initially listed it as a core symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder, which itself became a formal diagnosis in 1980. But the diagnostic criteria for PTSD has changed four times since the disorder was formalized. Today, survivor guilt is scarcely mentioned in the broader discussion around PTSD, and mental-health experts worry the condition is being chronically underreported and overlooked in trauma survivors. That includes veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, who are killing themselves at alarmingly high rates, despite unprecedented billions spent every year on efforts to destigmatize PTSD and encourage those suffering from the disorder to seek help. A majority of veterans who die by suicide do not take advantage of the V.A. mental-health services to which they are entitled. The common refrain is that veterans with PTSD avoid treatment because they fear being perceived as weak. But there is a much bigger problem. It is hard for people to recognize that the distress and messiness in their lives might be a result of trauma and that there are treatments out there that can help. A V.A.-sponsored study published in 2014 came to that same conclusion: “Many who suffer from mental-health problems do not perceive a need for help, and others grapple with uncertainty about whether their distress is severe enough to warrant it.”

I’ve grappled with that uncertainty myself. In many ways, the Army was good for me. I made a lot of friends and had some adventures. I was strong and healthy and clear. Between field training, Iraq and Afghanistan, I spent at least half of my six-year enlistment sober and learned that I could manage stressful situations without drugs and alcohol. But when those six years were up, I was more than ready to move on. I didn’t want the experience to define me. Worst-case scenario, I would become a full-time veteran, mired in nostalgia, pathologized and overmedicated, tethered to the system. Enrolling in the V.A. seemed like a big step in that direction. Unless I started seeing insurgents crawling out of the walls or went totally Rambo, I was going to be O.K. I did experience some notable effects, however, like the severe fear of flying I developed about halfway through the flight home from Afghanistan. I also started having frequent dreams about the apocalypse. Sometimes soldiers I knew appeared in them, one more consistently than the others. It is always the same scenario: We are standing face to face, and I am trying to explain something to him, I’m never sure what, and he just stares at me blankly, as if he’s annoyed or disappointed, or as if I’m making excuses, dancing around the point, and his impatience is an unnecessary reminder that I’m living on borrowed time.

My battalion arrived in Afghanistan’s Kandahar Province in the early summer of 2010, tasked with securing the district of Zhari, situated along the northern banks of the Arghandab, west of Kandahar City. Our area of operations was a swath of cannabis and poppy fields, pomegranate orchards, grape rows and secluded mud-brick villages without running water or electricity. The days were long and hot, and our gear was heavy. After dusk, insurgents and mountain lions lurked in the vast darkness beyond our guard towers, and it was quiet except for the singing of jackals and the occasional whoosh and boom of outgoing artillery.

I was a platoon medic with Bravo Company. Toward the end of the summer, we began a slow push into Taliban territory, advancing in stops and starts behind a ferocious barrage of heavy artillery and precision-guided bombs. In mid-November, we took the village of Sangsar, which Bravo Company would hold for the remainder of our time in Zhari. Chinooks deposited us on the outskirts of the village before dawn, and we went in expecting a fight, but the insurgents didn’t want to play ball. That evening we commandeered a farmer’s compound and slaughtered a chicken, and the Afghan soldiers cooked it in a stew with onions and marijuana. The following day, insurgents ambushed us as we were leaving a neighboring village, and we gave chase. Afterward, as we were en route back to the compound, a man in a white robe walked into the middle of our formation and exploded.

All that remained of the man were his two legs. Each was severed cleanly just below the knee, and both feet wore rubber sandals. Fanned out around them were eight or nine casualties, a mix of Afghans and Americans, wounded and dead and decapitated. I opened my aid bag and got to work, stuffing wounds and applying tourniquets, listening for the medevac helicopters. They couldn’t come fast enough. As the picture came into focus, I realized how easily one of those bodies could have been mine. Six members of my platoon were killed or badly wounded in an instant. Two of the dead were named Jacob, and they worked as a machine-gun team. The assistant gunner, 20-year-old Pfc. Jacob Carroll, went by Jake. The sight of his body knocked the wind out of me. Earlier, we had been standing next to each other, and a sniper round whizzed right between our heads. When we hit the ground Jake told me he was afraid. This was a soldier I’d never seen afraid of anything. “Doc,” he said, “I really don’t want to die.” He said it several times, as if he saw death coming and wanted me to stop it. As if he felt sure I could.

We left Afghanistan six months later and returned to Fort Campbell, Ky. The battalion held a memorial ceremony for the 18 soldiers we’d lost on the deployment. Many of their family members attended. Afterward, a woman stopped me in the parking lot and introduced herself as Jake’s mother. I was mortified. She started to ask something, but she was crying too hard to get the words out. I did not volunteer any answers. I was wearing my Class A uniform, and one of the ribbons on my chest was awarded to me for my actions the day of the suicide bombing. The tiny V in the center stood for “valor.” Now, under her scrutiny, it felt like a badge of shame. The way she looked at me, I imagined she was sizing me up, trying to discern whether her son died in incompetent hands. I wanted to comfort her, help clarify the mystery, tell her how peaceful Jake looked lying there as he died, but instead I wished her the best and walked away.

I moved back to Austin in the summer of 2012 to finish my bachelor’s degree. Nine months later, I skipped graduation, sold my truck and moved to New York City for an unpaid internship at Maxim magazine. I was 28 with no real journalism experience or knowledge of the industry, but I figured that if I just got my foot in the door, I’d be able to hold on long enough to learn the ropes. If the Army had taught me anything, it was the power of perseverance. The approach worked. The magazine eventually hired me full time as an assistant editor. I also met a woman, Sara, who wasn’t like anyone I had ever dated. She did yoga and had a six-figure job in advertising. My friends agreed she was out of my league. I was also drinking heavily, and when we decided to move in together she made it clear that the habit would need to stop.

The weeks and months blew by. I was laid off at Maxim, and in January 2016 I was hired at Task & Purpose, a news website that focuses on the military and veterans’ issues. I began every assignment promising to take it easier on myself, but inevitably the pressure would build until it nearly reached levels I had experienced as a medic. But New York City is a much different animal from the Army. With enough pizza, bagels, coffee, Coors Light, whiskey shots and bad cocaine, the endurance you develop as a soldier can very quickly go away. Sara and I started arguing a lot, mostly about my drinking. Other relationships started to fray, too. I was always too busy for everything: birthdays, weddings, my family. My health declined. Jake Carroll appeared in my dreams more and more. I told myself that such sacrifices had to be made for the sake of real, impactful journalism. But really, I didn’t know how else to operate. In the rare moments of respite, when I had a chance to step back and take a look at my surroundings, I couldn’t see a point to life.

Even as both my career and relationships came into jeopardy, the only solution I would allow myself to pursue was to work harder. Then I smacked into a wall. Words stopped coming to me. Sentences wobbled on the page. The nightmares grew increasingly grotesque. A friend who was a baseball aficionado suggested that I had caught a case of the yips. Whatever it was, I couldn’t write. The timing couldn’t have been worse. I had just signed on with a literary agent to write a book. For the first time in my life, I started seriously contemplating suicide.

Then in August 2018, my sense of taste inexplicably disappeared. I woke up one morning, and it was gone. Breakfast, a juicy burger, seafood linguine — everything tasted like gray pulp. Eventually, I made my way to the V.A. medical facility in Manhattan. I hadn’t seen a doctor since I left the Army six years earlier. A CT scan was ordered, and the emergency-room physician looked at the results and told me I may have had a stroke. That diagnosis was ruled out by an M.R.I., but I didn’t care. If anything, I was disappointed. I wanted a good reason to give up. The medical tests continued. A social worker stopped by to see me in my room and scribbled notes on a clipboard as I retraced the steps that had led me there. “Upon further questioning, patient reports that for the past year he feels like he’s been ‘in the weeds’ and endorses feelings of depression; admits to difficulty sleeping, decreased concentration at work, decreased interest in writing and passive feelings of suicidality,” she noted in my mental-health in-processing report. “He repeated multiple times that ‘he knew something like this would happen.’”

In December, I quit my job. After a long talk with my boss, we agreed it was the best thing for both of us. My co-workers gave me a going-away party, and I drank half a bottle of whiskey on an empty stomach. (Food quickly loses its appeal when you can’t taste it.) On the subway ride home, a stranger in an Army fatigue jacket brazenly sparked a joint. The friend I was with would later insist that the man was clearly homeless, but he didn’t look that way to me. Disheveled, sure, and angry — you could see it in his glassy eyes. He was young, about my age. He seemed surprised when I asked him if I could take a hit of his joint. It turned out to be something much stronger than marijuana. He laughed as I handed back the joint, and my last thought before blacking out was that he must be some sort of demon if he preferred what I was feeling at that moment to however he normally felt. When the world started to come back into focus some hours later, I was crawling in circles on my bedroom floor, but it was dark and Sara was screaming. I heard myself asking if I was in hell.

In Afghanistan, God and I had reached a mutual understanding. He knew I was an impostor, and I knew he knew. The realization hit me when I saw that Jake Carroll was dead. He had told me that he was scared to die at a moment when I knew death was right over our shoulders. While on patrol, my eyes were peeled because of a conversation I had overheard while on radio guard the night before. Our battalion commander had radioed in and requested to speak to the senior ranking officer on the ground. He told him that headquarters had received reliable intelligence that a suicide attack on Bravo Company was imminent. But that information was never related to First Platoon. I didn’t shut up about it as we were preparing to step off on patrol the following morning until my squad leader told me to stop being paranoid. We had heard rumors of suicide bombers in the area before. “I’m telling you, though, the B.C. sounded serious,” I said, and that’s where I left it.

At least one soldier remembered my warning in time to shoot the bomber as he approached our squad leader and shouted, “Allahu akbar!” I’m not sure what it was exactly about how the sky looked that led me to this conclusion, but it dawned on me with profound clarity as my eyes turned upward from Jake Carroll’s body: I could have stopped this attack. Had I really wanted him and the others not to die, I would have been more adamant in my warning. I convinced myself that the fact that I had split off to accompany another squad just before the explosion was proof that I saw it coming and let it play out in order to have an opportunity to shine. I wanted to be a hero. I wanted more stories for the book I planned to eventually write. I couldn’t fool God.

“Survivor guilt” is a problematic term because it describes two different experiences. Some psychologists acknowledge this by subcategorizing the condition into two types: “content survivor guilt” and “existential survivor guilt.” Essentially, the former describes the guilt people experience when they believe that something they physically did or failed to do directly contributed to another’s death. Say, for example, a medic fails to properly apply a tourniquet to a soldier’s amputated leg, and the soldier subsequently dies of hypovolemic shock. The medic then blames himself for the soldier’s death based on the belief that he died because the tourniquet wasn’t tight enough. Justified or not, that assumption is rational; it has a certain logic to it, even if it fails to recognize that the only person truly deserving of blame is the one who planted the bomb. In his recollection of events, the medic may play down the fact that he was being shot at while administering treatment. We tend to judge ourselves overharshly and overlook, discount or forget exonerating details. A common method of treating content survivor guilt therefore tries to emphasize those details to show the survivor why their guilt is outsize or unfounded.

Existential survivor guilt — in which the survivor feels culpable or contaminated merely for having survived — is resistant to logic, as from a rational point of view the innocence of the survivor is often not in question. Psychologists studying Holocaust survivors in the 1960s and 1970s often referred to it as “survivor syndrome.” The late Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor E. Frankl, a Holocaust survivor himself, preferred the notion of “survivor responsibility,” and believed that the best way to recover from trauma is to pursue a life of redemption. “The more one forgets himself — by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love — the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself,” he once wrote. “What is called self-actualization is not an attainable aim at all.” A more pathological interpretation that was embraced by many psychologists when survivor guilt was more widely recognized is that the guilt functions as a sort of buffer against nihilism. “The essential psychic process underlying survivor guilt is self-blame, which is a defensive omnipotent phantasy,” wrote the British psychotherapist Dr. Alfred Garwood in a 1996 study of Holocaust survivors. “In the traumatic environment created by the Nazis, self-blame was virtually the inevitable psychic defense.”

Combat is also conducive to the phenomenon. “I’ve found that most of the time the patient knows they are not responsible for anyone’s death but still feels that it is wrong or unfair that they survived, so they are stuck in this whirlpool, looking for answers that don’t exist,” says Dr. Hannah Murray, a clinical psychologist specializing in PTSD at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma. Murray began studying survivor guilt after realizing that there is currently very little guidance for clinicians on how to treat the condition. That includes in service members returning from war. “I believe some people have emotional consequences from trauma that aren’t PTSD, and because of the way the health care systems work here and in America, they won’t get taken care of,” she noted. “So I think there are a lot of people coming home from war who don’t get treatment and end up making bad decisions.”

Dr. William P. Nash, the former director of psychological health for the U.S. Marine Corps and a veteran of the Second Battle of Falluja, says the lack of awareness about survivor guilt extends specifically to the V.A. Nash himself currently works as a clinical and research psychiatrist with the V.A. in Los Angeles. He describes survivor guilt as “unrelenting and corrosive,” and agrees with Murray that it should be recognized as more than just a feature of PTSD. “It has not been studied enough, it has not been characterized, no one has figured out yet what its relationship is, if any, to depression, anxiety, PTSD or anything else,” he said.

For veterans of the war on terror, PTSD is one of the most common diagnoses by the V.A. More than 340,000 of us were receiving disability compensation for the disorder in 2017. While guilt is still listed as a possible symptom of PTSD, survivor guilt is not specified. Nor is it a stand-alone diagnosis. Which means there is no established set of diagnostic criteria to help mental-health professionals screen for it. That puts the onus largely on veterans to self-report the condition. Discerning between survivor guilt and actual guilt, however — a reasonable, justified awareness of culpability — requires a considerable degree of introspection. When you go to the V.A., the screening will try to determine whether you feel outsize guilt. You don’t. With survivor guilt you just feel that you did something terribly wrong and got six friends killed or mangled. You feel the guilt, but it doesn’t feel outsize; it doesn’t seem misplaced and unjustified. Your own innocence is precisely the thing you can’t see or feel.

Following the subway incident, I agreed to get help. It was free, after all, and I needed to salvage my relationship. The tests from the V.A. had come back negative, indicating that my loss of taste, which would take about six months to return, was psychosomatic. I started weekly sessions with a therapist who specializes in a form of trauma therapy called Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (E.M.D.R.). Basically, you hold a pair of electric buzzers and think about the worst moments of your life. Somehow it works — not even the experts are sure how, but it has to do with activating the two hemispheres of the brain in alternation — and it was more intense than I had expected. We did one short session to get me familiarized with the process, and I left feeling emotional but more or less fine. After the second time, I could barely sleep for days. “Joining the Army was a mistake,” I told Sara one night after she woke up to find me doubled over at the foot of the bed. I was recovering from a panic attack. She asked me why. But I couldn’t tell her what was going through my head. It was too dark.

The most troubling part of all this is that I actually liked being in Afghanistan. I didn’t want to leave. For the first year or so after we got back, I spoke openly and bluntly about the experience. Eventually, however, I started to notice a pattern: Whenever I talked about it, I’d leave the conversation feeling ashamed and become increasingly anxious over the rest of the day. So I decided to stop bringing it up. If a person asked questions and seemed genuinely interested in the truth, I would happily oblige. Otherwise, I’d keep it to myself. Except when I was drunk. I told my friends that if I started blabbering about Afghanistan at the bar, it was time for me to go home. But once I got going, the war stories flowed out of me like vomit. Inevitably, I’d wake up the next morning full of regret that compounded the hangovers, and I’d try to avoid my friends until the guilt subsided.

The subway incident compelled me to seek help, but it didn’t convince me that I actually needed it. That epiphany occurred about a week later, when I finally got around to rewatching HBO’s police drama “The Wire.” Toward the end of the first season, the protagonist, Detective Jimmy McNulty, becomes stricken with guilt after his partner is critically wounded during a drug bust. The raid was part of a bigger investigation that McNulty had forced into motion against the will of his chain of command. Stumbling drunk and tearful, he asks himself, “What the [expletive] did I do?” By this point in the show, we have seen sufficient evidence that McNulty is as selfish and manipulative as he is endearing. His guilt seems justified enough, and David Simon, the showrunner, could have let the character wallow in it for the remainder of the season. Instead, McNulty gets an unexpected pep talk from his commander, Maj. William Rawls, who doesn’t hesitate to remind McNulty that he hates his guts. “Believe it or not, everything isn’t about you,” the major says. “[Expletive] went bad. She took two for the company. That’s the only lesson here.”

I paused the show as the words sank in. Rawls might as well have been talking to me. And he was right. God hadn’t condemned me. I had.

Jan Scruggs, the former enlisted grunt who helmed the campaign to build the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, struggled with survivor guilt after returning home in the spring of 1970 full of shrapnel. Twelve years later, he stood before tens of thousands of Vietnam veterans on the National Mall and officially unveiled a monument to every American who fought and died in the war. It was the first memorial of its sort, intended also as both a permanent reminder to Washington of war’s human toll and a pilgrimage site for those whose lives were forever altered by it. Scruggs says the idea was inspired by Michael Cimino’s 1978 film “The Deer Hunter” — specifically, the scene in which Christopher Walken’s character, an Army commando, blows his brains out playing Russian roulette in Saigon. “That is what war is like,” Scruggs told me. “You can be a clerk typist and get hit by a rocket while at a Vietnamese massage parlor in Saigon. You can be an infantryman and not get a scratch in 12 months.” It was the same line of thinking that produced the Lucky Bastard Club.

Scruggs famously stood his ground through the political firestorm that erupted over Maya Lin’s design, thwarting a powerful cadre of politicians and businessmen determined to scrap the design for something more heroic. Scruggs thought that retroactively glorifying Vietnam would enshrine the rampant dishonesty and magical thinking that had allowed the conflict to drag on for so long and alienated those who served there. He also knew that the country’s eagerness to bury the truth only strengthened the impulse among veterans to self-induce amnesia of the trauma they experienced. As a graduate student of psychology at American University in the mid-1970s, Scruggs consumed the available literature on survivor guilt and believed the memorial could address the syndrome directly in individual veterans and catalyze a healing process. Hence the decision to arrange the 58,000-plus names on the memorial according to dates of casualty. An alphabetical arrangement would have made it easier for the vast majority of visitors to locate names on the Wall. Scruggs, however, was more concerned with helping veterans “who had experienced multiple K.I.A.s in a single action,” he told me. The idea was to “transport” them back to the mass-casualty event. The names are etched on glossy black granite so they appear superimposed over the veteran’s reflection to remind him that his own name could have just as easily been up there. When I asked him to explain the rationale for this, Scruggs suggested I look up Carl Jung’s concept of the hero archetype.

Jung proposed that the collective unconscious preserves a set of primordial patterns and impulses that are represented in archetypal characters that consistently appear in mythologies around the world, such as the trickster, the mother, the wise old man. Every archetype resides in an individual’s psyche, but a person’s goals, outlook and behavior may tend to be shaped by one more than the others. Jung’s hero is someone primarily driven by a desire to leave a mark on the world. To achieve this mastery, according to Jung, the hero must leave his comfort zone and undergo a series of ordeals that will force him to confront his limitations, including the fact that he can’t beat death. What he does with this knowledge after returning home determines whether he ultimately fails or succeeds. If he accepts himself for who he now knows himself to truly be, rather than whoever he started his journey wishing to be, he will unlock his own unique potential — become what he was “destined to become from the beginning” — and be at peace. If he does the opposite, he fails, and the price of failure is a life frozen in fear. “In myths, the hero is the one who conquers the dragon,” Jung wrote in his book “Mysterium Coniunctionis,” “not the one who is devoured by it. And yet both have to deal with the same dragon.”

Last month, I traveled to rural Virginia for a writing seminar hosted by The War Horse, a veteran-focused nonprofit news website that, among other things, supports and mentors young writers and journalists who served in the military. I planned to use the opportunity to workshop a book proposal. There were a total of 12 fellows, all former combat medics or Navy corpsmen.

Had I read The War Horse Fellow Handbook, I would have known that the program was for veterans “who want and need to tell stories from their time in service.” My book is about soccer in the Middle East. There was also this essay, however, which originally was due back in April. When I pitched the idea to my editor, I had grossly underestimated how much soul-searching would be required. Turned out, I had no clue who I was. For months, I wrote in circles around myself, devoting tens of thousands of words to a panoply of irrelevant topics, everything from the Indian Wars and Irish gold miners to primitive cave drawings and driving conditions in West Texas. Some drafts read more like suicide notes. The wheel-spinning took a mounting toll. As my father put it: “This has gone way beyond what you can handle and everyone around you can handle.” But I refused to let go. Even as the debt piled up and my relationship fell apart, even as more lucrative opportunities fell by the wayside, I kept at it, slogging toward a fading dream, determined to prove to myself that I still had it, that I hadn’t lost my mojo, that I hadn’t reverted back to the guy I was before the Army, the guy who always gave up, who expected others to shoulder his burdens, who was doomed to fail. Now, standing in a room full of people who would happily help get me over the finish line, I wanted to turn back in the other direction.

As introductions began, I was brainstorming excuses when one fellow, an Air Force veteran named Jen, said something that caught my attention. She had worked in a combat-support hospital near Kandahar City in 2010. The story she had come to Virginia to tell began with her and her colleagues running across the hospital landing zone to a Black Hawk full of dead American soldiers. I noted some familiar details in her brief description of the casualties as they appeared when the helicopter crew chief slid open the cargo door — the missing heads, the charred flesh. She mentioned that only one of the bodies was still wearing a name tape and that someone asked what it read. “Carver,” she said. “He had beautiful green eyes.” At which point I volunteered to introduce my story next. “Those were my guys,” I began. “I put them in that helicopter.”

Five days later, when it was time for everyone to go back to wherever they came from, back to our respective ecosystems, nobody wanted to leave. We exchanged emails and phone numbers and promised to stay in touch. All of us had done this dance before. Military life is full of hard goodbyes. But you are always looking forward to something: block leave, the end of a deployment, reuniting with friends and family, retirement. Then you get out, and you can’t stop looking back. That’s why we had gone to Virginia — to figure out how to carry the stories. To unstick ourselves from the past. Because moving on isn’t the same thing as running away. That was my takeaway, at least. I realized that along with the traumatic memories, I had also buried the side of me who can cope with them. It was liberating to be in a place where war and its repercussions aren’t kept shrouded in mystery. And humbling. I remembered why I got into journalism in the first place. War is a failure to communicate, and nothing good comes from veterans’ keeping quiet about it. I am proof of that.

Over these past several months, I have gotten to know my grandfather better than I knew him when he was alive. And I can see that his depth perception became discombobulated somewhere between the world he saw ending beyond the window of his cockpit and the one he found himself in when it didn’t end. He squeezed every ounce of energy into life immediately after the war — and then life kept going. The formula was unsustainable. I recently came across photographs of him that I had never seen. In one, he appears alongside my grandmother in his Class A uniform, smiling wide with a martini in one hand and his straight black hair greased and parted. They look genuinely happy. As far as I can tell, he never saw the point of getting sober. “I hate this place,” he once said of the nursing home where he resided, adding an expletive for emphasis. That is the only conversation between us I can remember.

I’m told he started drinking during the war to calm his nerves. A B-24 was no easy machine to handle, especially under constant fire. As the author Stephen E. Ambrose noted in his book “The Wild Blue,” at higher altitudes, the bomber became a literal icebox, with temperatures plunging so low that the pilot’s oxygen mask would freeze to his face. My grandfather also wore an oxygen mask the day he died. But there wasn’t a bottle within reach. I went to see him several days before he died. He looked small and skeletal in his nursing gown. His eyes remained wide open and fixed on the ceiling for the duration of our visit, and periodically he would gasp, and spittle would fly from the hole in his throat. Thinking back on it now, as I sit in the apartment that I shared with Sara for more than three years, typing at my kitchen table, which will soon no longer be my kitchen table, and eye the suitcases waiting for me by the door, I see the crossroads that lies just ahead and see that vision of my grandfather looming at the end one of them. But at least now I can see that the other road goes somewhere better.

Adam Linehan is a freelance writer and journalist. He served as a United States Army medic and was deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.