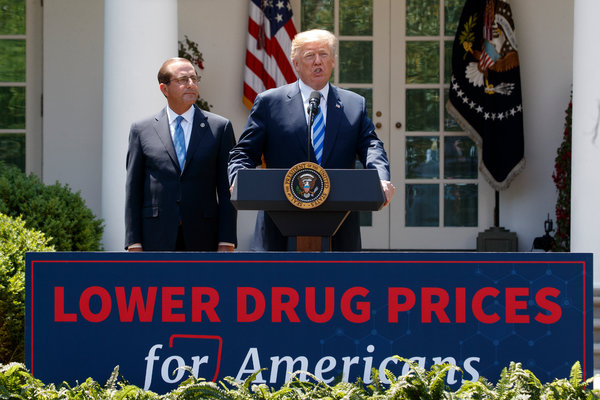

The Trump administration has made lowering drug prices one of its top priorities, and last week it unveiled a proposal that could vastly rewrite the way drugs are sold in the United States.

The proposal takes aim at the secret deals that drug companies strike with pharmacy benefit managers, the industry intermediaries that negotiate the price of drugs for insurers and large employers.

These after-the-fact discounts, called rebates, have come under harsh criticism and are blamed for helping to push up the list price of drugs, which consumers are increasingly responsible for paying.

Under the proposed rule, released on Thursday, pharmacy benefit managers would lose the legal protections that allow them to accept rebates from drug companies for brand-name drugs covered under the Medicaid and Medicare government programs. Any such discounts would instead have to be credited at the pharmacy counter when patients fill a prescription.

The Trump administration says this could result in significant savings for people 65 and older, who increasingly have been forced to pay out-of-pocket costs based on the rising list prices of drugs. People who are covered by Medicaid, the health care program for low-income Americans, generally pay little to nothing out-of-pocket.

If carried out, the plan is likely to upend the overall market for prescription drugs. Drugs paid for through Medicare accounted for 30 percent of the nation’s retail drug spending in 2017, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But whether the rule will ultimately be adopted is still unclear. It faces an intense lobbying battle — and perhaps a legal one — from the pharmacy benefit managers, and the politics will also be tricky.

I have a Medicare prescription drug plan. How will this affect me?

Let’s answer this question with a question: Do you take an expensive medication for a chronic condition?

If you need expensive drugs, your out-of-pocket costs are likely to go down. Under the current system, your deductible and any coinsurance — a requirement that you pay a percentage of a drug’s cost yourself — is based on something close to a drug’s list price.

Under the new plan, those amounts would be based on a lower net price, or the cost after discounts had been deducted. The proposal estimates that seniors’ monthly out-of-pocket drug costs would decline, on average, $1.70 to $2.74 a prescription in 2020.

That average, however, obscures the significant savings some people will see if they have extremely high drug costs: Some could save about 30 percent on their out-of-pocket costs, the administration estimated.

Not everyone will benefit. Pharmacy benefit managers secure rebates only when there is competition between manufacturers who sell similar brand-name drugs, like two kinds of blood pressure medications.

But many costly drugs — cancer treatments, for example — have little or no competition and carry either no rebates or small ones. Patients needing these drugs would not see extra savings.

If you don’t take expensive drugs, your monthly costs are likely to rise because premiums will go up. Insurers would no longer be able to apply rebate money from the drugs to lower premiums.

The typical Medicare beneficiary will see costs rise $2.70 to $5.64 a month, estimates indicate.

About one-third of people with Medicare drug plans will directly benefit from lower out-of-pocket costs, but it’s unclear how the other two-thirds will see an advantage. That’s why some consumer groups, such as AARP, have opposed similar proposals.

The trade-offs — slight increases in costs for most people and sizable help for those who need expensive drugs — would make the system more fair, proponents contend.

After all, insurance typically works by spreading the high costs of caring for a few across a large group, including healthy people. Patients needing very expensive treatments do not pay the full cost.

I regularly reach the so-called doughnut hole, or Medicare coverage gap. Will this help me?

Seniors enter the Medicare coverage gap — requiring them to pay for a bigger share of their drug costs — once spending for their medications exceeds $3,820 in a year.

With lower net prices under the new plan, many seniors wouldn’t reach that threshold until later in the year, and some wouldn’t reach it at all.

Fewer people would also reach the “catastrophic phase,” once out-of-pocket drug spending exceeds $5,100, at which point the federal government picks up much of the bill. Seniors must still pay 5 percent of a drug’s cost, but that too would be based on the lower net price.

Drug makers are expected to benefit because they must help pay for the costs of drugs once seniors enter the doughnut hole. If fewer people reach the doughnut hole, the companies pay less. And if fewer people enter the catastrophic phase, the government would save money, too.

Will this end up costing taxpayers more or saving the government money?

The Trump administration says that a lot will depend on how companies react. If the plan takes effect next year, it could cost the government an extra $2.8 billion to $13.5 billion that same year.

But longer-term projections indicate that the plan could wind up saving the government nearly a hundred billion dollars, if drug spending and drug pricing methods change.

“It’s clear from the proposal that the administration is genuinely unsure about how pharmaceutical companies and insurers and P.B.M.s will respond to this proposal,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate professor of law at Washington University in St Louis.

How would this affect the 156 million Americans who are insured through an employer?

The short answer is it wouldn’t — at least directly. The only way rebates could be eliminated entirely for all insurance plans, including those provided by an employer, would be for Congress to pass legislation.

Many companies are already introducing plans that allow employees to share in some, if not all, of the discounts when they go to the pharmacy counter.

About a quarter of large employers expect to have a program like that this year, according to the National Business Group on Health, which represents large employers, and the largest pharmacy benefit managers are already working with large companies to pass on savings.

How likely is this to happen?

Industry analysts are generally skeptical the administration will be able to get these proposals in place by 2020. Although the drug industry has come out in favor of the plan, pharmacy benefit managers are likely to pursue legal action against it.

In addition, Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other powerful Democrats have already voiced opposition. “The Trump administration’s rebate proposal puts the majority of Medicare beneficiaries at risk of higher premiums and total out-of-pocket costs, and puts the American taxpayer on the hook for hundreds of billions of dollars,” Speaker Pelosi said in a statement.

You can also expect heavy lobbying from the nation’s largest insurers, since they are now joined at the hip with the pharmacy benefit managers. Aetna is now part of CVS Health, Cigna owns Express Scripts, and both Anthem and UnitedHealth Group have in-house pharmacy operations.

These combined companies “have a bigger voice at the table,” said Ana Gupte, an analyst at SVB Leerink.

I’m still confused. Can you give me an example?

In a speech last week, Alex M. Azar II, the health and human services secretary, pointed to the story of a woman named Sue, whose annual income was $24,000 a year and who could not afford the $7,200 a year in out-of-pocket costs for a drug to treat a genetic skin condition.

“This backdoor system of kickbacks isn’t set up to serve Sue, and it isn’t set up to serve you, the American patient,” Mr. Azar said in remarks to the Bipartisan Policy Center.

But Sue’s case underscores how any one proposal to fix high drug prices is unlikely to solve the broader problem. (This is one of several proposals the Trump administration has put forward in the past year.)

Sue’s out-of-pocket costs would fall, but perhaps not enough to make a difference in her budget: After a 33 percent discount, her out-of-pocket costs would still be $5,544 per year.