I hate stunt food. You will not see me ordering a steak wrapped in gold leaf. I won’t do a caviar bump. I don’t care about that time you drank wine with a snake in it.

Nor am I a fan of the Cajun turducken, which is a boned chicken wrapped in a boned duck wrapped in a boned turkey with some dressing tucked in. It does a disservice to all the birds involved. It also spawned the piecaken, a four-dessert monster I hesitate even to mention because I don’t want to encourage it.

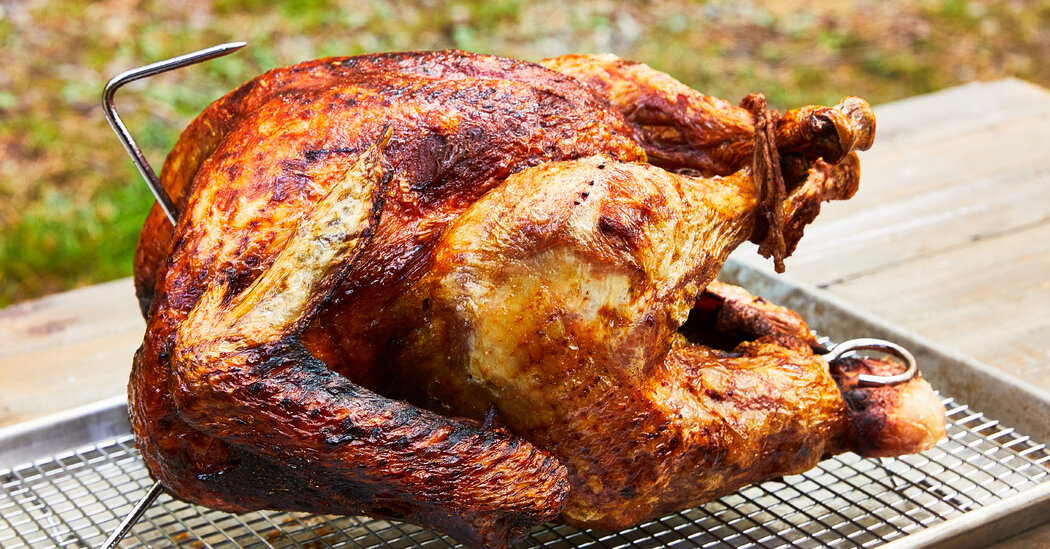

I do, however, love a deep-fried turkey.

I know that standing in the backyard and lowering a turkey into four gallons of boiling peanut oil has all the markings of stunt food. And it’s nothing I would have considered until I moved to the South.

Five years ago, I went to a friend’s house for Thanksgiving. An ex-boyfriend was in the back, frying a turkey. Let me tell you, my friends, I had never tasted turkey as delicious — and I have cooked, tasted or tested at least a hundred turkeys in my day. The oil crisps the skin until it crackles and seals in moisture, creating a succulent umami bomb dripping in juice.

For cooks, the fried turkey is a logistics game changer. It frees the oven for baking rolls or accommodating that guest who shows up with a surprise casserole she needs to pop in for a half-hour.

Did I mention that the turkey is done in only about 30 to 45 minutes, depending on its size?

No one knows who first decided to fry a turkey, but Louisiana made it famous. In Cajun country, portable propane burners and tall, narrow aluminum pots were already a popular way to boil crawfish, crab and shrimp. The rigs, it turned out, were also great for frying fish and chicken. It was not too much of a leap for someone to say, “Hold my beer and pass me the turkey.”

The Cajun chef and television personality Justin Wilson fried them on his show in the 1970s. An enterprising United Press International reporter traveled in 1982 to the tiny town of Church Point, La., where locals injected turkeys with Italian dressing spiked with Cajun seasonings and fried them.

But it was Dale Curry, a food editor at The Times-Picayune of New Orleans, who took fried turkey from small-town oddity to quirky national star in 1984, when she printed a recipe from a chef in the French Quarter. It called for using a horse syringe and a plastic rope, but failed to warn readers not to execute the recipe under a carport or near a building.

At least two structures burned that year.

“So I was watching the evening news that Thanksgiving night,” Ms. Curry recounted in her farewell column in 2004, “and a New Orleans resident with a house flaming behind him told a TV news reporter, ‘I’ll never use another one of those recipes.’ (I silently thanked him for not mentioning my name or publication.)”

Since then, fear of turkey frying has swept the nation. Deep-fried-turkey-mishap videos are their own online genre, with pots of oil spewing like Mauna Loa. Tell someone from New York that you’re frying a turkey, and they act as if you’re proposing a swim in the Gowanus Canal.

I’m not going to lie: The job requires a lot of equipment. You can buy a kit for less than $100 that provides everything you need. It does not include common sense, though. You have to add that yourself.

If you set things up properly, use caution and don’t get drunk or distracted, frying a turkey is perfectly safe.

“What I love about the deep-frying is once you get the method down, it’s fairly easy,” said the Atlanta chef Steven Satterfield, who for a decade has been frying turkeys for his family’s holiday. “It’s just so passive. You just keep an eye on the temp and let it ride.”

It’s a very social way to cook, too. Watching a bubbling vat of oil with a whole turkey in it can be mesmerizing. Inevitably, there will be a lot of standing around the pot and chatting.

“It’s like a water feature,” Mr. Satterfield said.

Like me, Mr. Satterfield is not a fan of injecting the turkey or coating it in spices, which tend to burn in the oil. He lets his turkey chill for a couple of days in a dry rub of salt and brown sugar perfumed with orange zest and dried herbs like rosemary and thyme, or spice mixtures like garam masala, which he rinses off before he pats the turkey dry.

I don’t use those extras in the dry brine because I think they get lost in the frying. Mr. Satterfield told me I was wrong: “It offers a subtle flavor profile that makes its way under the skin and into the surface area of the muscle.” (Flex on, Mr. Cheffy McChefferson.)

Deep-fried turkey has its drawbacks. You won’t have drippings, which I find essential for good turkey gravy. I solve the problem by roasting a thigh or giblets with some onions and carrots ahead of time, and then deglazing the pan to create a drippings hack. Also, your house won’t have that Thanksgiving smell. The solution? Roast those gravy parts the same day, or buy a turkey candle.

The biggest challenge is what to do with those four or five gallons of used oil. Some recipes suggest you strain it and save it for another use. I might reserve a little for a batch of fries or maybe some shrimp, but trust me when I tell you there is no “other use” for that much oil.

You can take several approaches to getting rid of it. There are new products to stir into warm oil to create a scoopable, biodegradable solid.You can funnel it back into the original containers and call a private oil-recycling company, or check with your local solid-waste department to see if they take cooking oil or can suggest organizations that do.

Don’t let the potential for burning down the garage or getting stuck with gallons of oil deter you. Buy a rig, get some peanut oil and deep-fry a turkey.

You’re welcome.