That night, I woke up crying. My husband held me. There were dirty clothes on the floor. I realized that, like all profound loss, miscarriage was a private drama that would unfold against the quotidian backdrop of my life. I sought company in art, looking for writing as raw and unsparing as my experience. I didn’t want to feel better, but I did want to feel understood. Eventually, I came across a feminist cartoonist named Diane Noomin, and on a whim, ordered her work “Baby Talk: A Tale of 4 Miscarriages.”

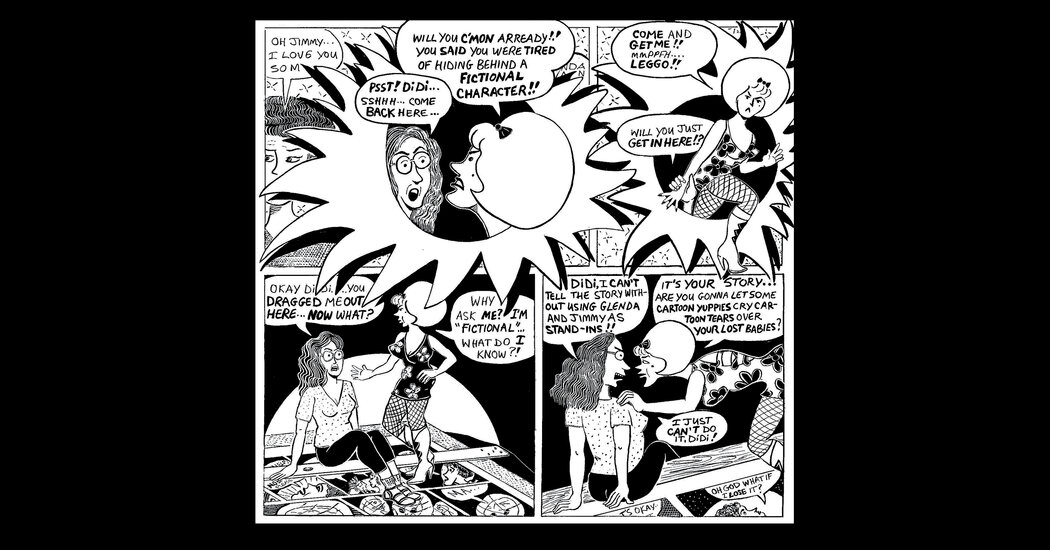

“Baby Talk” is a 12-page comic about the artist’s recurrent miscarriages. Published in 1994, it is striking, even today, for its unvarnished account of pregnancy loss. In black-and-white drawings and irreverent dialogue, she captures everything from the high-highs of giddily picking out baby names to the low-lows of peering into the toilet bowl at a miscarried fetus. (“What is it?” Noomin wonders. “It looks like liver.”) Noomin, who died recently, was a pioneer of underground comics — she collaborated with Aline Kominsky-Crumb and was introduced to her husband, the cartoonist Bill Griffith, by Art Spiegelman — but I didn’t know any of that when I read “Baby Talk.” I only knew that reading her story allowed me to feel the full range of my own grief.

As with Noomin, I wasn’t only sad that I’d lost my pregnancy, I was also angry and deeply ashamed. Her story is confessional, but she writes about feeling too embarrassed to tell anyone she’d miscarried and the impulse to pretend that everything was OK. I felt that way, too. When I broke the news to a few friends and family, I was humiliated. Without realizing it, I’d recast myself as a failure rather than as a person undergoing an impossibly hard thing. What’s radical about “Baby Talk” is that it isn’t about the babies Noomin lost; it’s about her. Hiding in bed with a copy of her work and a monster pad between my legs, I felt compassion for her, which was the entry point I needed to feeling compassion for myself.

Part of what I had missed in the miscarriage forums and support groups was a sense of who we all were outside of this experience. Reading “Baby Talk,” I could see the pattern printed on Noomin’s bedsheets, what her hair looked like when getting a shot of Valium (messy), her dreams, her profession, her voice. She was anxious, obsessive and funny. She reminded me of friends I hadn’t seen in months. The isolation of miscarriage inside of the isolation of a pandemic was an awful Russian doll, but reading her story offered a sense of intimacy. I could see a whole person, a whole story.

Noomin waited years after her losses before writing about them, and the conflict between wanting to fictionalize her story and to tell it honestly is dramatized through conversations with an alter ego. I don’t have an alter ego, but I recognize this tension. There’s still a part of me that wants to keep my miscarriages a secret, despite also feeling compelled to write about them.